Vibrant blue ultramarine may have been an expensive pigment, but it was not without problems. Over time, the paint surface can acquire a blanched appearance, so that these areas are now lighter in colour than the artist intended. Many of Vermeer's paintings suffer from this effect.

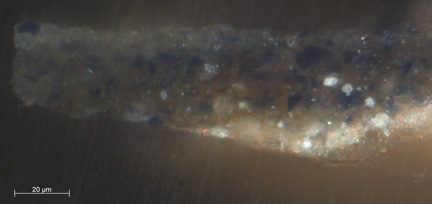

A paint sample was taken from the blue upholstery in Young Woman standing at a Virginal where the ultramarine blue paint layer is particularly severely deteriorated and blanched [figs.1 & 2].

The cross-section of this sample clearly shows a pale band at the top of the paint layer where the paint layer has altered, though one large particle of ultramarine is clearly visible at top left [fig.3].

The deterioration process of this pigment is not well understood, though, as with lead pigments there is some indication that ultramarine may interact in some way with an oil binder influencing the changes in its chemistry on ageing. The evidence for this comes from the observation that oxalate, a compound that is associated with deterioration of the binding medium, has often been found in ultramarine-containing paint. Here it was detected by ATR-FTIR imaging of the cross-section [figs.4–8]. Although some oxalate is present throughout the sample, it is most concentrated in a region at or just below the surface.

In addition, X-ray mapping of the sample revealed other chemical changes. The blanched uppermost portion of the paint layer is rich in potassium, sulphur and lead, probably in the form of potassium lead sulphate which is also likely to be a deterioration product. [figs.9–15] shows a backscattered electron SEM image of the sample overlaid with X-ray maps (in red) for potassium, sulphur/lead, calcium and sodium together with spectra from spot analyses from the blanched area of the sample and for the blue pigment particle at top left.

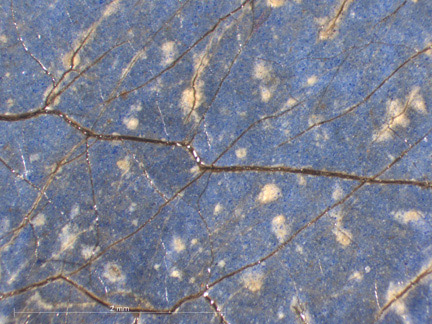

On the painting itself, this deterioration seems to be more marked along the edges of microcracks where the paint appears paler and whitish. The small translucent white lumps across much of the surface of the blue paint of the chair upholstery in 'Young Woman standing at a Virginal' also proved to contain potassium lead sulphate, so seeming to be a more noticeable manifestation of the same chemical change. They are clearly visible pushing through the blue paint layer and dark underpaint in [fig.6]. The cross-section of a sample that includes one of these lumps [figs.17–20] shows the dark underpaint and a few particles of ultramarine over the pale brown ground layer.

Over this is the large pale protrusion. In this sample it seems clear that the potassium lead sulphate is forming around silicate-rich pigment particles (ultramarine, green earth and yellow earth are all forms of silicate present in the sample) [ figs.21–27].

Analysis of 'The Art of Painting' (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) by researchers in The Netherlands also revealed the presence of potassium lead sulphate. In this case it was postulated that the source of the potassium and sulphate may have been a particular alum-containing gelatine glue mentioned in 19th-century recipes and possibly employed in a relining of the painting undertaken at that time.1 It is possible that a material used in the conservation of our painting at some time in the past – for example the relining of the painting before its acquisition in 1892 – is the source of potassium. However it is also possible that the potassium may come from some other, as yet unidentified component of the paint or indeed from the ultramarine pigment itself.

Boon et al., working on samples taken from 'The Art of Painting', suggest that lead soaps are an intermediary in the formation of potassium lead sulphate (palmierite).2 This type of alteration is also postulated by Van Loon who suggests that the first step in this reaction is the formation of lead and potassium soaps which are mobile and can migrate towards the surface of paint layer. These soaps then react with carbon dioxide and sulphur compounds at the surface to form insoluble complex salt mixtures such as potassium lead sulphates – the presence of oxalates adding to their insoluble character.3

Helen Howard is Scientific Officer – Microscopist at the National Gallery. This material was published to coincide with the exhibition Vermeer and Music: The Art of Love and Leisure.

Explore more topics

Original methods and material

- Support and ground

- Infrared examination

- Vermeer's palette

- Binding medium

- Paint application

- Secrets of the studio

Time and transformation

- Altered appearance of ultramarine

- Fading of yellow and red lake pigments

- Drying and paint defects

- Formation of lead and zinc soaps

2. One mass of lead soap has partially reacted into potassium lead sulphate. This is not thought to be an original component of the paint layer but a stray paint particle that ended up on the surface of the painting, see footnote 1, pp. 238–9 and 329–33.

3. A. van Loon, 'Colour Changes and Chemical Reactivity in Seventeenth-Century Oil Paintings' in 'Molart Report', vol. 14 (2008), p. 157.