The genesis of the composition

Gossart’s most important source is the Monforte altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes (Berlin: fig.37). It is not known where this very influential painting, which is now cut at the top, was in Gossart’s time. The original composition can be partially reconstructed from reversed versions attributed to the Master of Frankfurt (fig.47).73 Many very obvious parallels may be made between NG2790 and the reconstructed Monforte ‘Adoration’, with its magnificently-attired kings and attendants, the bystanders in the middle ground, the broken architecture and the flying angels. Gossart has adapted his figures of the Virgin and Child from Hugo’s panel, while his Balthasar and his Melchior were inspired by Hugo’s Balthasar. Fascinated by Hugo’s views through ruined buildings to distant landscapes, Gossart extended the vista and, more daring even than Hugo, opened up at the centre of his painting a vast recession towards mountains seen across an enormous distance.

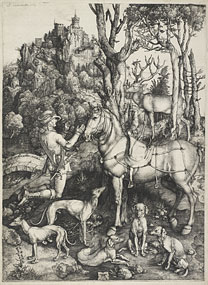

There is one obvious borrowing from Dürer: the dog on the right in NG2790 is taken from Dürer's engraving of ‘Saint Eustace’ (fig.49). The other dog comes, in reverse, from Schongauer’s engraving of the ‘Adoration of the Kings’ (fig.50); and it seems that Caspar’s hat and the men behind Melchior are inspired by the same print (fig.32). In NG2790, the young man at the right carrying the sword and mantle, the man laying his left hand on the left shoulder of the former, the horseman wearing a turban and the rocky landscape behind them find their counterparts in the print. There are, moreover, points of resemblance between the two Virgins and the two Children. In the engraving, the attendant on the right appears to be carrying the youngest king’s cloak; whereas the mantle carried by Gossart’s young man does not seem to belong to Melchior. Gossart’s underdrawn horseman is more like Schongauer’s than his painted figure. There are probably further borrowings from another Schongauer print in the same series, the ‘Nativity’ (fig.51), where the figures of Saint Joseph, the shepherds and the angels holding the scroll are not dissimilar, and where the broken stones in the foreground, the plants growing among them and the creepers climbing over the ruined arch may very well have influenced Gossart’s ideas. Gossart’s Child is not unlike the Child in Schongauer’s engraving of the ‘Virgin with the Parrot’ (fig.52).

View enlargement in Image Viewer

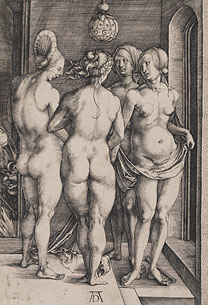

The steep perspective in which the ruined buildings are seen and parts of the ruins themselves are reminiscent of Dürer’s engraving of the ‘Nativity’, dated 1504 (fig.51). The angels are all to some extent similar to Dürer’s angels and may be compared with those in the woodcuts of his ‘Apocalypse’ and ‘Life of the Virgin’ series. The pose of the second angel from the left may have been inspired by Dürer. He recalls the woman on the right in Dürer’s engraving of ‘Four Witches’, dated 1497 (fig.53). The many figures of babies, on the capitals, on the frieze, on Balthasar’s gift and on Caspar’s sceptre, are influenced by classical precedent and may be based on antique sources, on Italian prints or, more probably, on designs by Dürer (compare his engraving of the ‘Three Putti’, B.66).

Although making use of van der Goes, Schongauer, Dürer and very likely other sources, Gossart has created a composition that is entirely his own and completely characteristic. Even if some of the heads of the subsidiary figures are hastily painted, there are no fundamental differences in technique between them and the other heads and there is no reason to believe that Gossart delegated any significant part of the painting to assistants. The story that he laboured on NG2790 for seven or eight years seems to have been invented at the end of the eighteenth century but he must have expended a great deal of time and effort on this picture.74