The story of the colour brown

At first glance the colour brown may seem less interesting than more vibrant hues, but throughout art history it has been vital. One of the most immediate and ancient sources of brown pigments is the earth itself.

Earth that contains naturally occurring iron and manganese oxides produces a range of brown hues, from warm, golden ochre to deep umber. These earthy shades of brown have been used by artists for centuries but, as we will see, they have also been mixed using blends of vibrant colours.

Brown as an underpainting colour

The oil sketches of Peter Paul Rubens are a glimpse into the early stages of his creative process. In ‘A Lion Hunt’, Rubens applied a transparent grey-brown wash of paint, so loosely that the striations – the fine, parallel lines created by the paintbrush – are visible. He then used brown pigments to swiftly sketch in the forms of the rearing horses, applying touches of white, black, and red to the otherwise brown monochrome sketch to add emphasis.

Rubens made oil sketches like ‘A Lion Hunt’ as preparatory works to help plan his compositions, but the technique he uses is an insight into how he constructed his finished paintings. In his full-scale painting of Samson and Delilah, Rubens prepared the panel with a loose wash of yellow-brown paint, made from a natural earth pigment.

Rubens's technique was not unusual – brown was commonly used to paint in the first layers before the more expensive, colourful pigments were applied on top. However, Rubens has deliberately allowed the yellow-brown layer to show through in the completed painting. Look closely at the folds of Delilah’s sleeve and you’ll see the striated brown wash exposed in the warm shadows.

The symbolism of brown

The use of brown earth as an underpainting colour reveals how crucial it is in the painting process, but does it ever come to the forefront? When considering the religious significance of colours in Christian art, you might immediately think of red, symbolising the blood of Christ, or blue, often associated with the Virgin Mary. However, brown could also carry deep symbolic meaning.

A striking example can be found in ‘The Man of Sorrows’, part of a 13th-century diptych. Recent cleaning revealed that the cross had been painted using three different tones of brown. These tones are thought to symbolise the three different types of wood traditionally believed to have been used to make the cross: fir, palm, and cypress. In this context, brown transcends its role as a mere colour and becomes a potent evocation of the crucifixion.

Brown also played an important role in the identity of certain Christian communities. Saint Francis of Assisi, who founded the Franciscan Order in the 13th century, wore a brown habit – or robes – to embody humility and simplicity.

As an earthy and practical colour, it contrasted with the lavish clothing worn by many of the wealthy and powerful at the time. Franciscan monks followed his example, as shown in Rembrandt’s portrait of a Franciscan friar. The humility of his brown robe is echoed in the modesty of his gaze, and he appears to be lost in thought.

Shifting hues

Not all the browns we see in historical paintings were originally intended by the artists. Over time, certain pigments have proven unstable, leading to transformations in colour. One notable example is Diego Velázquez’s ‘Portrait of Philip IV of Spain in Brown and Silver’. The king’s tunic, which now appears brown, was originally a deep purplish-brown hue.

An even more dramatic case is found in Paolo Veronese’s ‘Four Allegories of Love’. Throughout the series the sky was painted with smalt, a cobalt-based blue pigment, which has deteriorated over time. The once vibrant blue has faded to a muted brownish-grey, giving the scenes an unintended overcast appearance.

Such transformations are a reminder that the colours we see in historical paintings today are not always the same as those the artist originally applied. The chemistry of pigments, combined with the effects of time and environmental factors, has sometimes turned bright, luminous colours into shades of brown.

Mysterious brown eyes

Perhaps one of the most enigmatic uses of brown can be found in Sandro Botticelli’s ‘Portrait of a Young Man’. This portrait is remarkable because, instead of adhering to the traditional profile view common in Italian Renaissance portraiture, the sitter faces the viewer directly, gazing out with deep, brown eyes that match his plain fur-lined doublet.

For years, art historians speculated that this might be a self portrait of Botticelli himself. However, recent research has confirmed that while the painting is indeed by Botticelli, the identity of the sitter remains unknown. This leaves us with an intriguing mystery – who do those expressive brown eyes belong to?

Van Dyck Brown

Anthony van Dyck’s use of brown was so iconic, that a colour was named after him. The portrait painter would often use Cassel earth, a dark brown traditionally sourced from peat-rich soil in Germany. In his ‘Equestrian Portrait of Charles I’, Van Dyck used Cassel earth mixed with yellow to produce the various shades of golden green in the foliage. He became so well known for his use of the pigment, that today it is commonly known as ‘Van Dyck Brown’.

Chromatic browns

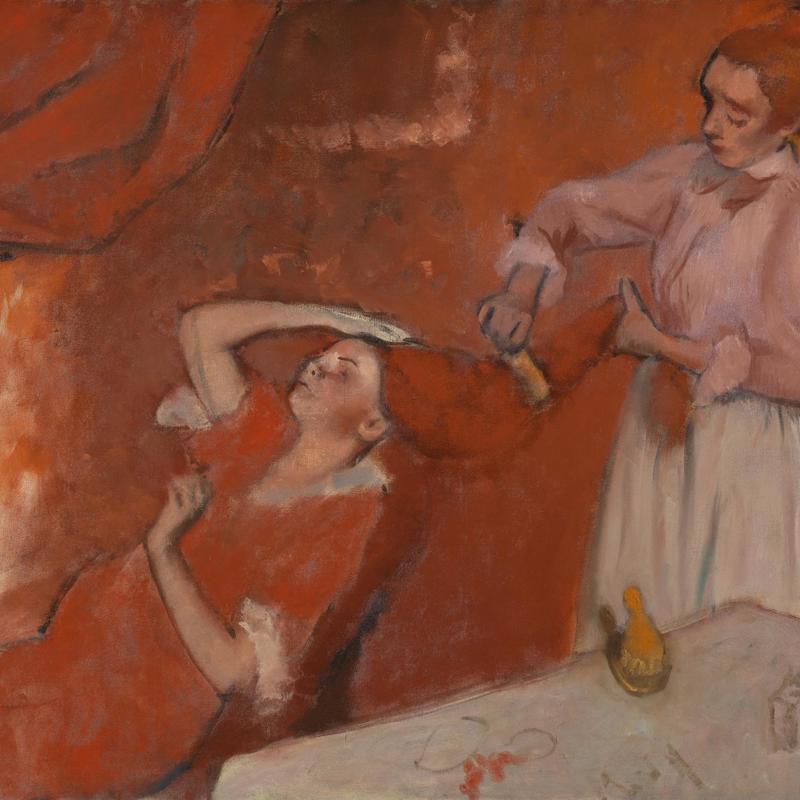

While brown earth pigments were the backbone of traditional painting, in the 19th century the Impressionists sought to move away from these conventional materials. Instead, they mixed colours to create their own nuanced browns.

In ‘Petit Bras of the Seine at Argenteuil’, Claude Monet made a palette of warm and cool browns from complex mixtures of blues, oranges, reds and yellows. By carefully adjusting the proportions of these colours, he achieved a spectrum of browns ranging from warm ochres to cool mauves. Rather than being a static and dull shade, these browns are full of bright colour and appear to shimmer in the misty atmosphere.

Brown is far from an unremarkable colour. As Rubens’s oil sketches show, it is a foundational colour in artistic practice, but it has also come to the forefront of many paintings, like in the symbolic hue of the Franciscan friar’s robes in Rembrandt’s portrait, or in the deep eyes of Botticelli’s unidentified sitter. Brown may not be as immediately eye-catching as red, yellow, or blue, but it is a colour full of dynamism and meaning.