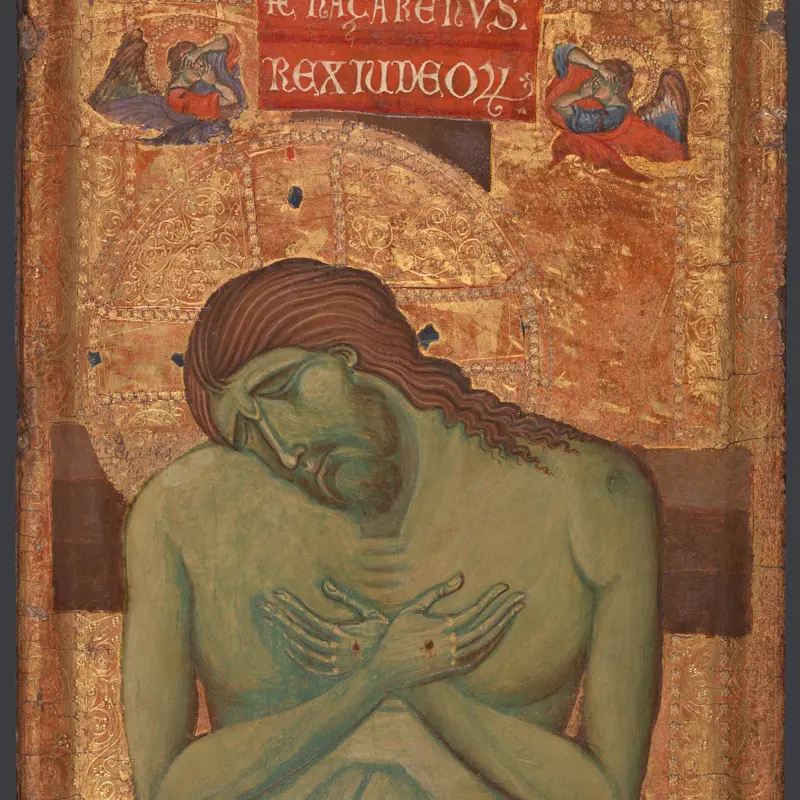

Master of the Borgo Crucifix (Master of the Franciscan Crucifixes), 'The Man of Sorrows', about 1255-60

About the work

Overview

In 1999 this panel was reunited with its pair, an image of the Virgin and Child. Together they formed a diptych, a painting made of two panels joined with a hinge.

Christ is shown on the Cross, just after his death – a type of image called the Man of Sorrows. Its origins lie in Byzantine painting (the art of the Eastern Christian empire) but it became popular in the west in the thirteenth century. The Cross has been painted with three different shades of brown, representing the three trees from which it was thought to be made: fir, palm and cypress, interpreted as symbolising the Trinity (God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost).

There were many Franciscan friaries in the eastern Mediterranean during this period, so the religious order was familiar with Byzantine imagery. The Man of Sorrows was popular with the Franciscans, as they were particularly devoted to the contemplation of Christ’s suffering.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Man of Sorrows

- Artist dates

- Active about 1250 - 1269

- Part of the group

- Umbrian Diptych

- Date made

- About 1255-60

- Medium and support

- Egg tempera on wood (probably poplar)

- Dimensions

- 32.3 × 23 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1999

- Inventory number

- NG6573

- Location

- Room 65

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 13th-century Umbrian Frame (original frame)

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Dillian Gordon, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Italian Paintings before 1400’, London 2011; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2008Byzantium 330-1453Royal Academy of Arts25 October 2008 - 22 March 2009

Bibliography

-

1929R. Marle, 'Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth Century in the Collection of Monsieur Adolphe Stoclet in Brussels', Pantheon, IV, 1929

-

1949E.B. Garrison, Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index, Florence 1949

-

1956D. Lion-Goldschmidt, Adolphe Stoclet Collection: Selection of the Works Belonging to Madame Feron-Stoclet, Brussels 1956

-

1964R. Pallucchini, La pittura veneziana del Trecento, Venice 1964

-

1967W. Kermer, Studien Zum Diptychon in der sakralen Malerei, Düsseldorf 1967

-

1969J.H. Stubblebine, 'Segna di Buonaventura and the Image of the Man of Sorrows', Gesta, VIII/2, 1969, pp. 3-13

-

1978H.W. van Os, 'The Discovery of an Early Man of Sorrows on a Dominican Triptych', Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, XLI, 1978, pp. 65-75

-

1982J. Cannon, 'Dating the Frescoes by the Maestro di S. Francesco at Assisi', The Burlington Magazine, CXXIV/947, 1982, pp. 65-9

-

1982D. Gordon, 'A Perugian Provenance for the Franciscan Double-Sided Altar-Piece by the Maestro di San Francesco', The Burlington Magazine, CXXIV/947, 1982, pp. 70-7

-

1984D. Gordon, 'Un crucifix du Maître de San Francesco', Revue du Louvre, XXXIV/4, 1984, pp. 253-61

-

1990H. Belting, The Image and Its Public in the Middle Ages: Form and Function of Early Paintings of the Passion, New York 1990

-

1998E.B. Garrison, Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index, London 1998

-

1998D. Gordon, 'Anonymous Umbrian Master: The Virgin and Child and the Man of Sorrows', National Gallery Review, 1999

-

1999National Gallery, The National Gallery Review: April 1998 - March 1999, London 1999

-

1999Anon., 'New Acquisition', National Gallery News, 1999

-

1999J. Cannon, 'The Stoclet "Man of Sorrows": A Thirteenth-Century Italian Diptych Reunited', The Burlington Magazine, CXLI/1151, 1999, pp. 107-12

-

2000G. Finaldi, The Image of Christ, London 2000

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2004H.C. Evans, Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261-1557) (exh. cat. Museum of Byzantium Culture, 10 August - 15 November 2004), Thessaloniki 2004

-

2008R. Cormack and M. Vasilaki, Byzantium 330-1453 (exh. cat., Royal Academy of Arts, London), London and New York 2008

-

2011Gordon, Dillian, National Gallery Catalogues: The Italian Paintings before 1400, London 2011

Frame

This thirteenth-century panel and its counterpart The Virgin and Child each have an original engaged frame, the mouldings dowelled and glued to the front of the panel. The water-gilded frame decoration is ornate, featuring engraved foliage and punch-tooling with four-petal flower heads.

The two panels were joined with three hinges, forming a portable diptych.

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the group: Umbrian Diptych

Overview

These panels once formed the left and right wing of a diptych, a painting made up of two parts joined by a central hinge. Holes on the left edge of the panel depicting the dead Christ match up with those at the right edge of the panel with the Virgin and Child; these once held hinges. Both panels have the same dimensions and the backgrounds are decorated with the same patterns and markings. The reverses are both painted to imitate red porphyry, a type of stone.

The images belong to the Byzantine (Eastern Christian) tradition. The diptych may have been made for a Franciscan friar – a member of the religious order which followed the teachings of Saint Francis and placed particular emphasis in their prayer upon Christ’s suffering. The Order’s presence in the eastern Mediterranean after the Fourth Crusade of 1204 (one of a series of medieval religious wars) meant that they would have been familiar with Byzantine imagery.