The colour orange is a constant presence throughout art history. It has been used for thousands of years across the world, from the horses that decorated cave paintings in Prehistoric France to the Impressionists’ radical explorations of light in the 19th century.

But just where does it come from? And what came first – the name of the colour or the fruit?

The history of orange

The earliest uses of the word ‘orange’ as a name for the colour were recorded in the 16th century, when orange trees were brought to Europe from Asia.

But that’s not to say that the colour itself didn’t exist before the name was adopted in the English language. Before the arrival of the fruit, the colour was referred to as ‘yellow-red’. In fact, orange pigments can be seen as far back as on the cave paintings at Lascaux in France, or in the tombs of Ancient Egypt.

Orange has had many different connotations throughout history. In paintings depicting Bacchus or Dionysus from Ancient Greek or Roman mythology, they are often seen in orange robes, a colour used to highlight the sense of hedonism and frivolity.

This is in direct contrast to eastern cultures – in Buddhism or Hinduism, orange is a sacred colour, representing fire and purity. Buddhist monks wear orange robes, to remind them of their commitment to a life of purity and simplicity. The use of orange for the robes also has a practical history, as dyes such as saffron and turmeric were easy to get hold of.

Orange pigments through history

While orange can be created by mixing yellow and red, it is the pure pigments that produce the most vibrant colours. Apart from the natural orange ochres, many of the orange pigments used in the ancient world and right up into the Renaissance were incredibly toxic, with high levels of arsenic.

Let’s take a closer look at orange pigments, where they come from, and which National Gallery artworks you can spot them in.

Orange ochre

Ochres are colours that come directly from the iron oxides found in the ground. Early cave paintings such as those found at Lascaux feature colours created by iron oxides and these continue to be used today to create colours such as orange ochre. The natural mineral is washed to remove sand and other impurities. It's then dried and the pigment is ground and sieved.

You’ll find orange ochre in many of the National Gallery’s paintings including Rembrandt’s ‘Self-portrait at the age of 63’, Canaletto’s ‘The Stonemason’s Yard’ and Camille Pissarro’s ‘Fox Hill, Upper Norwood’.

It continues to be used by artists today, and if a pigment includes the word ‘Mars’, then it contains a synthetic iron oxide pigment.

Realgar

As a result, its use throughout history varies hugely. It has been found to have been used artistically by ancient civilisations in India, and on manuscripts by medieval artists. Yet the toxicity can’t be underestimated. In fact, it was used as rat poison in the Middle Ages!

Despite its dangers, Venetian colourist Titian used realgar in his work, including on the orange drapery on the figure with the cymbals just behind Bacchus in ‘Bacchus and Ariadne’.

Realgar was also used by Dutch flower painters of the 17th and 18th centuries. One of the leading flower painters of her time, Rachel Ruysch uses the pigment to create some of the vibrant flower petals in her ‘Flowers in a Vase’.

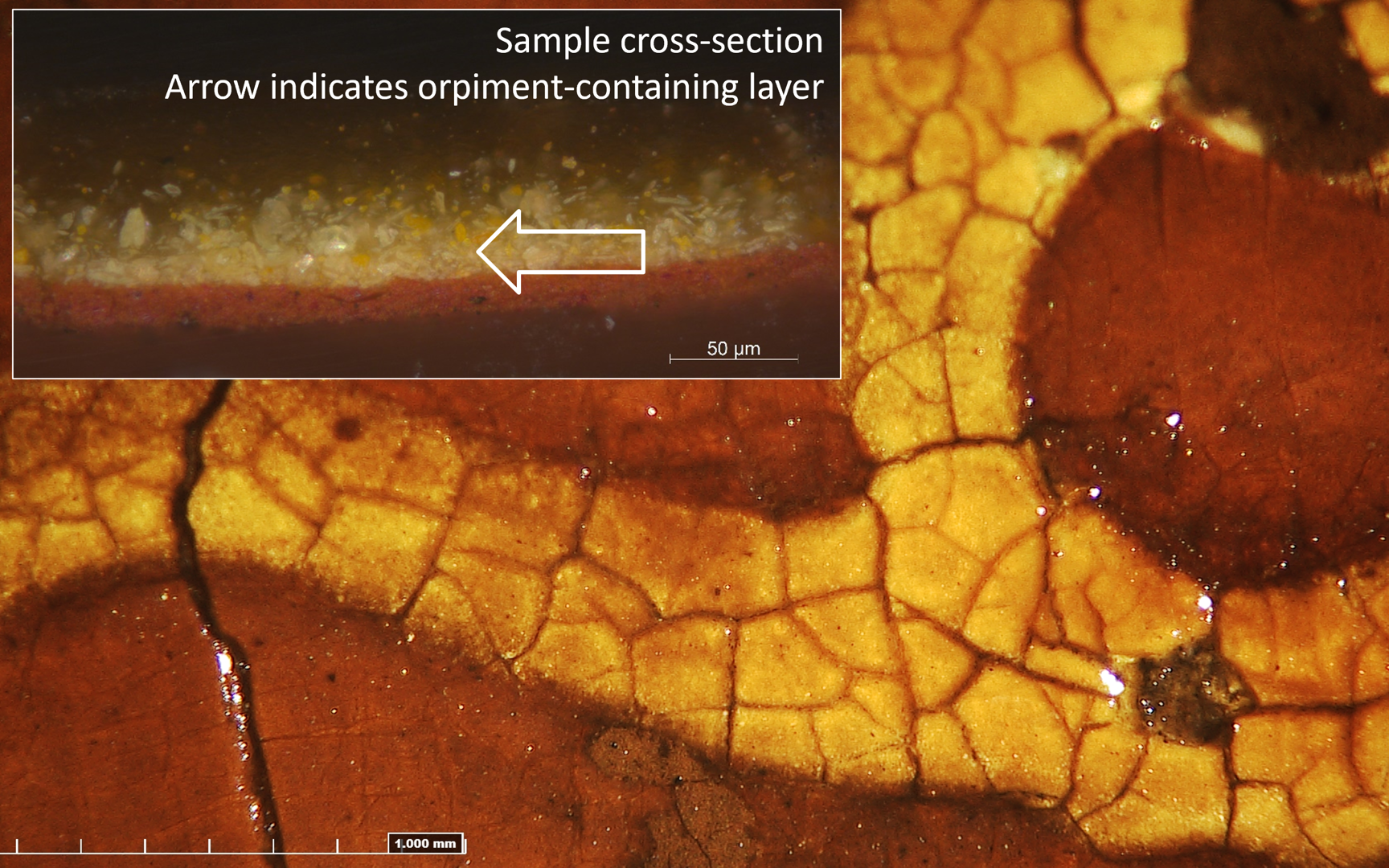

Orpiment

Another early use of orange comes from a mineral called orpiment, which has a natural golden yellow tone. It is another pigment which is toxic, with a high arsenic content.

It was traded in the Roman Empire and used as a medicine in China, and for many years it was ground down and used as a pigment. It wasn’t until the 19th century that its use was phased out, when other, much safer, pigments became available.

It has been found to be used on early European panel paintings and manuscript illuminations, such as Margarito d’Arezzo’s ‘The Virgin and Child Enthroned, with Scenes of the Nativity and the Lives of Saints’, one of the oldest paintings in our collection, dating from 1263-4. It was also used by 16th-century Venetian artists for example Paolo Veronese and Jacopo Tintoretto.

Chrome orange

Chrome orange was the first synthetic orange pigment to be created after French chemist Louis Vauquelin discovered the element chromium in 1797. This resulted in the discovery of using lead chromate as a pigment, and eventually the introduction of chrome orange in 1809.

Scientific analysis of Edouard Manet’s ‘Eva Gonzalès’ – painted in 1870 – suggests that the artist may have used either chrome orange, or the closely related chrome yellow pigment, to paint this portrait of his only formal pupil and fellow artist Eva Gonzalès.

Cadmium orange

Cadmium pigments followed in the mid-19th century. Cadmium is a by-product of mining and smelting of zinc, and artists were drawn to the brilliant and long-lasting colour. While many artists today still use cadmium, it is toxic so care should be taken especially when working with the loose pigment.

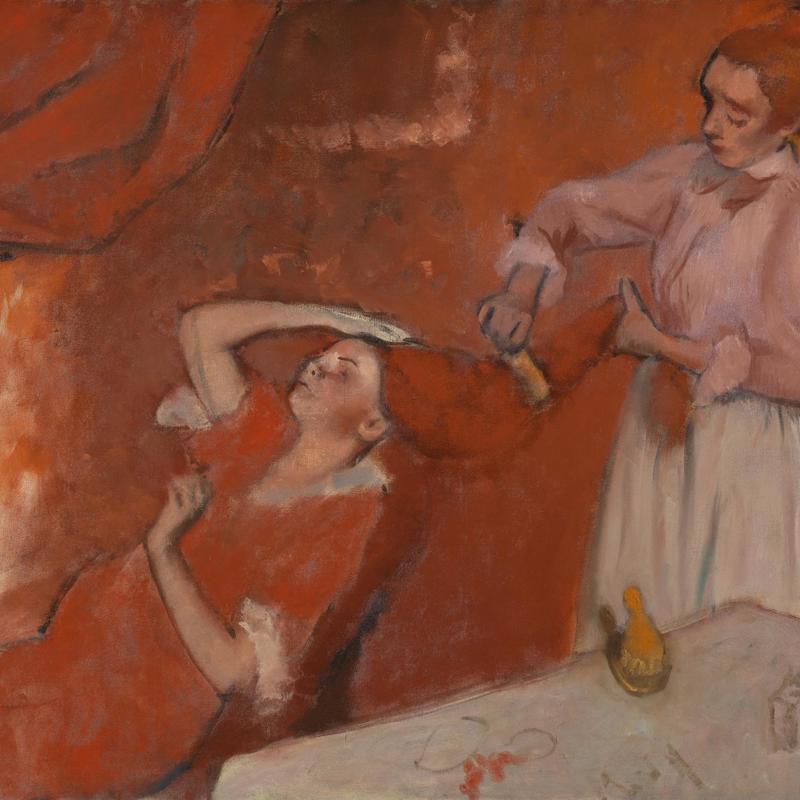

Cadmium orange became popular with the Impressionists, who used the pigment to capture natural light in their works, such as in Monet’s ‘Water-Lilies’.

Orange in the 20th century

The use of orange continued to be popular in 20th-century art, with significant use in the work of Francis Bacon, who used the colour to strikingly horrific effect in ‘Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion’ (Tate).

And while artists continued to use orange in their work, chemists continued to develop new pigments, sometimes accidentally!

Pyrrole red was accidentally invented in 1974 by Donald G. Farnum, a chemist at Michigan State University. When a Swiss company found his report, they patented a process for making the pigment. The most famous use of the original Pyrrole red is in the car industry, on the iconic Ferrari. Pyrrole orange is available to contemporary artists as a less toxic alternative to cadmium orange.

Who knows what future oranges might be stumbled upon in future. Whatever their properties, artists will continue to find ways to use them to convey a range of emotions – from the alarming to the uplifting.