Is white a colour?

If you wander around the National Gallery, you’ll see white paint everywhere, from the clouds of John Constable’s ‘The Hay Wain’ to the white silk damask robes of Giovanni Bellini’s ‘Doge Leonardo Loredan’. But if you ask a scientist, they might claim that white doesn’t actually exist as a colour. So how can that be? Well, technically, white is what we see when all wavelengths of light are reflected off an object. However, white pigments have existed in art for thousands of years, and continue to be invaluable for artists around the world.

What does the colour white represent?

White has been associated with purity and religion for many hundreds of years. It was worn by priestesses in Ancient Rome and Egypt and today the Pope famously wears a white cassock, while white ihram clothing is worn by Muslims during the Hajj pilgrimage.

In Medieval art, a white unicorn was considered to be a symbol of Christ and the purity of the Virgin Mary. Interestingly, the white unicorn is also a symbol of purity and innocence in Celtic mythology.

In patriarchal Western cultures, a white wedding dress has traditionally symbolised the bride's virginal innocence and represents new beginnings, but it wasn’t until Queen Victoria got married in a white lace wedding dress that the trend really took off.

White can also be linked to mourning. Many people in Asia wear white at funerals, and in Medieval Europe reigning queens would often wear white in mourning, a tradition that was reintroduced by the Dutch royal family in the early 21st century.

Calcium carbonate

As with the history of many colours and pigments, we can trace the first uses of white right back to the prehistoric period. Our ancestors would have used chalk for their mark making, otherwise known as calcium carbonate, a soft limestone.

This chemical compound proves invaluable in buon fresco painting, where an artist would apply colour directly to wet plaster. As a result, calcium carbonate would form when carbon dioxide in the air combined with the calcium hydrate in the wet plaster. This results in the paint being part of the wall, since the 16th century frescoes have been detached from walls and transferred to new supports, such as Spinello Aretino’s ‘Two Haloed Mourners’.

Today, calcium carbonate isn’t typically used in artists’ paints, apart from frescoes, but it is still a key ingredient in other art materials such as traditional glue-based gesso, and in the production of archival artist paper.

Lead white

The pigment lead white is a basic lead carbonate. It’s found naturally in the mineral hydrocerussite, which was mined from around 4000 BC in southern Europe and Egypt. It can also be produced synthetically, a process that has taken place since the 5th century BC.

Lead is incredibly poisonous if it is inhaled or ingested, or even if it gets into the body via a cut, it can build up and eventually affect the digestive and nervous systems. While the Romans were aware of the effects of lead poisoning, they still used lead for water pipes and cooking pots, and even as a sweetener in their food!

Lead was also used in cosmetics, with many women knowingly slowly poisoning themselves in their desire for pale and flawless skin. Most famous perhaps was Elizabeth I, who would have used a mixture of white lead and vinegar directly onto her skin. Despite these dangers, lead was regularly used in cosmetics up until the early 1900s.

In the art world, lead poisoning wasn’t inevitable for all artists, despite the quantity of artists using lead white. It’s worth considering that apprentices in artists’ workshops were more likely to be mixing paints, and were therefore more exposed to the loose pigment than the famous artists of the day. Once the particles are in a binder, the risks drastically reduce, but they don’t disappear. It is suspected that Michelangelo, Vincent van Gogh and Francisco de Goya all suffered from lead poisoning. Painter’s colic came to refer to the severe stomach pains and constipation that artists suffered as a result lead poisoning.

So why did artists risk using lead white? What were the benefits? Well, lead white is a fast-drying pigment when mixed with oil, which was hugely beneficial particularly when using white for underpainting and it was regularly used to prime canvases. It was also very useful for adding highlights, being a very opaque pigment.

While lead white exists in hundreds of paintings in the Gallery’s collection, particular highlights include Titian’s ‘Noli me tangere’, with Christ’s loin cloth and robe in bright white, as well as Mary Magdalen’s linen sleeve.

The bright white of Aechje Claesdr’s white ruff and cap in Rembrandt’s ‘Portrait of Aechje Claesdr.’ owes its vibrancy to lead white, as do the highlights on the robes in El Greco’s ‘Christ Driving the Traders from the Temple’.

Next time you visit the Gallery, take a look at your favourite painting and wonder at what toxins might lie within. (But don’t worry! You’re perfectly safe with the pigments locked up in the paintings.)

Today, sales of lead white pigments are restricted and often expensive, and in the UK and the EU lead white is only available to conservators.

Zinc white

With the health complications resulting from the use of lead white, alternatives were sought.

One such replacement, used by artists since the 19th century, was zinc white, first developed by French chemist Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau in the 1780s. It was costly to produce at first, but these costs were reduced as production methods improved. It was sold as a watercolour in the 1830s by Windsor & Newton as ‘Chinese white’, in relation to the popularity of Chinese porcelain at that time.

Its popularity with oil was less successful due to its slow drying time and lack of flexibility when dry, which means it is more susceptible to cracks. As a result, lead white continued to be the most popular white pigment in the 1800s. Having said that, examples of zinc white at the National Gallery include Van Gogh’s ‘A Wheatfield, with Cypresses’. Van Gogh used zinc white in the white areas of the sky, with the blue areas also mixed with cobalt blue.

Titanium white

At the start of the 1900s, titanium white became available as another alternative to toxic lead white. Bright and opaque, by the 1930s it had replaced lead white as the most popular on the market. It has a high tinting strength, which means you don’t need to add much to other colours to make an impact. However, it is very slow drying with oil paint.

Lithopone

A pigment to rival lead white and zinc white in the late 19th and early 20th century was lithopone, a mix of Barium sulphate and Zinc sulphide. It became hugely popular in the early 20th century, but this changed in the latter half of the 1900s due to its expense.

In 'La Terrasse at Vasouy, The Lunch' Edouard Vuillard seems to have used either zinc white, titanium white or lithopone, perhaps because the artist preferred the purer white colour of zinc and titanium pigments over the warmer tint of lead white.

20th century experiments

Artists of the 20th century have explored white in more unusual ways, including Ben Nicholson’s ‘1935 (White relief)’ and Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘White Paintings’ series, both of which exclusively use the colour white.

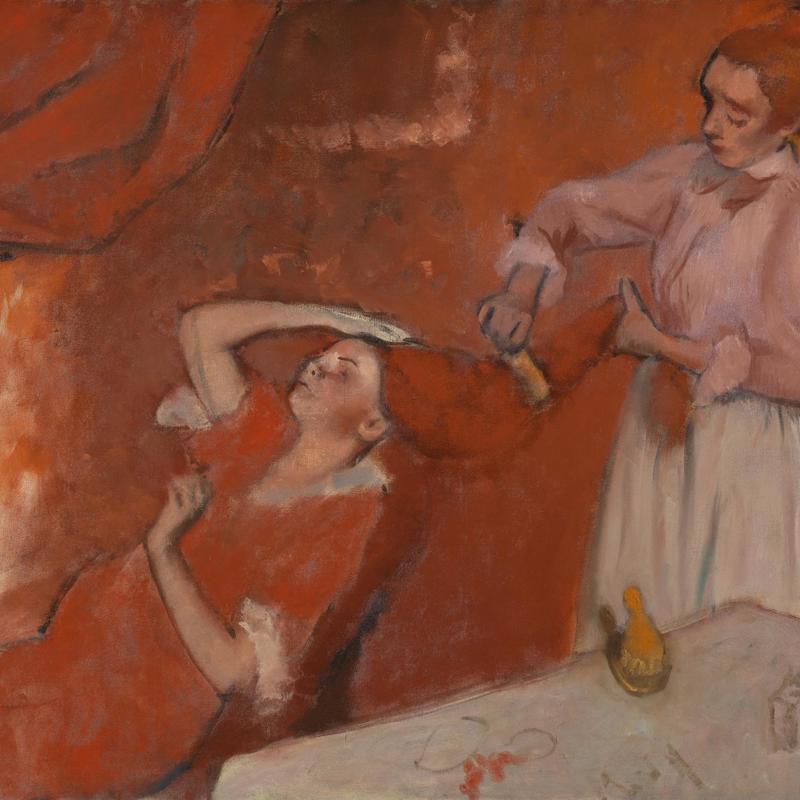

Within the National Gallery’s collection, it’s a challenge to find a work that doesn't use some form of white pigment, whether it be in the frescoes of Renaissance Italy or the shimmering works of the Impressionists.

It can help build shadows and light, has often been a symbol of purity and is a vital part of the artist’s palette – though it was not without danger!