Technical notes

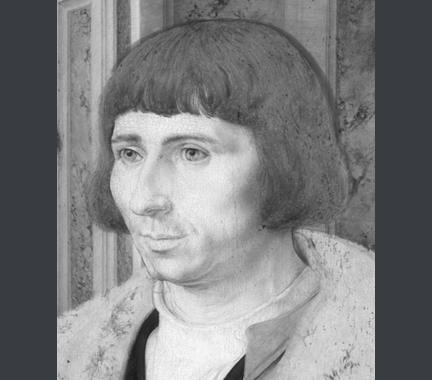

The painting was cleaned in 1888 and in 1994–5. The condition is very good, though there are areas of abrasion in the mouth and the architecture and some of the detail of the hair and fur has been lost. Small rings of damage, for example in the hair, may be due to attacks by mould.

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

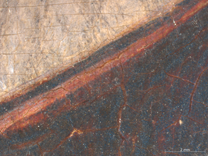

The panel is made up of two oak boards, radially cut, set vertically and vertical in grain; the join, reinforced with dowels, is 17.3 cm from the left at the lower edge. The support is about 15 mm thick in the middle but is stepped at the back around all four edges (fig.1) to a thickness of 5 mm (measured at the centre of the lower edge). This would have allowed the panel to be inserted into the grooved rebate of the lost original frame, which must have been constructed around the panel.2 Dendrochronological investigations have established that the wood is Baltic oak and that the 193 growth rings of the first board were formed between 1297 and 1489. The 336 rings of the second board were formed between 1143 and 1478.3 The reverse of the join is covered by a strip of red lead(?) paint; on the reverse are the remains of a paper label bearing traces of writing, now illegible. The ground and priming on the obverse of the panel continue to all four edges but the paint stops just short of the top and bottom edges; it is conceivable that the lateral edges have been slightly trimmed. The panel was not in its final frame when the ground and priming were applied. It may have been held in a temporary framing structure while it was painted; as the rosary beads do not continue to the lower edge, the artist clearly realised that the edges would be concealed by the rebates of a frame (fig.2).

View enlargement in Image Viewer

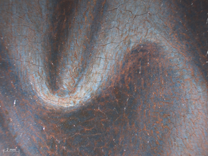

The ground is chalk in animal glue and there is a pale salmon-pink priming containing lead white tinted with red lead.4 It is applied in broad brushstrokes that give a texture visible in many places, even though paint has been applied on top (fig.3). Underdrawing in a liquid medium, applied over the priming, is sometimes visible through the paint, which has become transparent with age (fig.3) ; it is more completely revealed by infrared reflectography (figs.4, 5). The drawing consists of simple freehand outlines. No hatching has been found but areas where hatching is most likely to have been used – the man’s coat and sleeves – are not penetrated by infrared radiation. There are some changes: the contour of the chin was painted to the left of where it was drawn; and the standing collar was painted to the right of where it was drawn. The contour of the end of the nose was painted beyond the underdrawn line (fig.4). There are underdrawn lines indicating the positions of the shoulders beneath the fur collar. The architecture is also drawn, somewhat approximately, with the help of a straight edge. Some of the lines are ruled longer than was necessary and the underdrawing for the curved parts of the architecture is not always followed (fig.5).

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

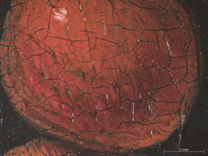

The man’s collar is very dark purple and a cross-section of a paint sample shows that it is painted with azurite and red lake applied on a deeper and more red layer containing mainly red lake mixed with some black (See fig.6 left, and photomicrograph m19 in Image Viewer). Two types of red lake, each with a different fluorescence under ultraviolet (UV) light, are present: that in the lower layer has an orange fluorescence characteristic of lakes prepared from madder dyestuff; while that in the upper layer does not fluoresce but appears pink under UV and is likely to have been prepared from an insect dyestuff.5 The purple sleeves were not sampled but can be seen under a stereomicroscope to have been painted in the same way, except that the bluer purple surface paint is lighter in hue (fig.7). Unusually, the yellow pigment seen in the man’s rings and in the green cord on which the rosary beads are strung does not seem to be lead-tin yellow; its appearance under a stereomicroscope may indicate that it could possibly be orpiment (See fig.8 below, and photomicrograph m30 in Image Viewer). The medium of the priming is linseed oil. Only one sample of the paint was analysed, from the pale grey architecture at the left edge: there the medium is walnut oil.

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

The man's rings and the beads of his rosary are painted without reserves on top of his fingers and his gown respectively. The paint of the fur is very thin and in places the priming is left uncovered. In the flesh of his neck (fig.9), his nails, the folds of his shirt (fig.10) and the lit edge of his white standing collar (See photomicrograph m15 in Image Viewer), the paint has been feathered. Gossart’s paint has beaded in the eyebrows (See photomicrograph m3 in Image Viewer), the hair (fig.11) and the fur (fig.12). The rosary beads (fig.13) and the chipped areas of architecture directly above the man's head are rendered wet-in-wet (fig.15). A ‘sgraffito’ technique has been used in the modelling of the volutes (See fig.14 below, and photomicrograph m34 in Image Viewer). Some of the lines of the architecture are incised into the paint (See fig.16 below, and photomicrograph m35 in Image Viewer).

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

View enlargement in Image Viewer

Further Sections

- Introduction

- Provenance and exhibitions

- Technical notes

- Description

- The identity of the sitter

- Attribution and original function

- Date

3. Report by Peter Klein, dated 3 December 1999, in the NG dossier.

4. Chalk (calcium carbonate) was identified by EDX analysis in the SEM. It was confirmed by FTIR analysis which also showed that the binding medium was proteinaceous and therefore probably animal glue. The identification of the pigments in the priming was confirmed by examination of cross-sections of paint samples. See reports in NG Scientific Department files by M. Spring (dated July 1994) and by J. Pilc (dated 9 January 1995).

5. Notes in NG Scientific Department files by M. Spring (10 January 1995).