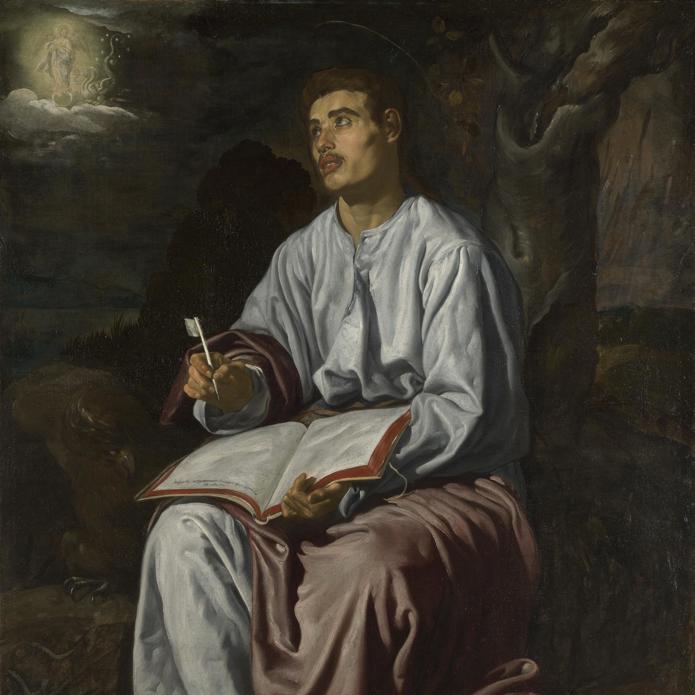

Diego Velázquez, 'Saint John the Evangelist on the Island of Patmos', 1618-19

About the work

Overview

On the Greek island of Patmos, Saint John the Evangelist had a vision of the Woman of the Apocalypse, which he recorded in the New Testament Book of Revelation. Here he sits with an oversized book in his lap, his quill pen poised, and looks towards the tiny illuminated female figure hovering in the clouds above him.

She is accompanied by a dragon – the devil – ready, according to Saint John, to devour her baby as soon as it is born. She is given wings, faintly visible behind her, to escape.

This woman is often understood to be the Virgin Mary, mother of Christ. The vision is associated with the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, the belief that Mary was herself conceived without sin. This painting is paired with The Immaculate Conception, which shows the Virgin standing on a moon and surrounded by stars, like in the vision we see here. Both are among Velázquez’s earliest known works.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- Saint John the Evangelist on the Island of Patmos

- Artist

- Diego Velázquez

- Artist dates

- 1599 - 1660

- Part of the series

- Two Paintings for the Shod Carmelites, Seville

- Date made

- 1618-19

- Medium and support

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 135.5 × 102.2 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought with a special grant and contributions from The Pilgrim Trust and the Art Fund, 1956

- Inventory number

- NG6264

- Location

- Room 30

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 16th-century Italian Frame

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Neil MacLaren, revised by Allan Braham, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Spanish School’, London 1988; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2024The Illustrious GuestGallerie d'Italia - Palazzo del Banco di Napoli23 April 2024 - 14 July 2024

Bibliography

-

1813London, National Gallery Archive, NG72/36/1: Letters about the provenance of NG 6424 by Bartle and George Frere, 1813

-

1956The National Gallery, The National Gallery: January 1955 - June 1956, London 1956

-

1963National Gallery, Acquisitions 1953-62, National Gallery Catalogues, London 1963

-

1970N. MacLaren and A. Braham, The Spanish School, 2nd edn, London 1970

-

1981A. Braham, El Greco to Goya: The Taste for Spanish Paintings in Britain and Ireland (exh. cat. The National Gallery, 16 September - 9 November 1981), London 1981

-

1983A. Martínez Ripoll, 'El "San Juan evangelista en la isla de Patmos", de Velázquez, y sus fuentes de inspiración iconográfica', Áreas. Revista de ciencias sociales, 3-4, 1983, pp. 201-8

-

1987J.F. Moffitt, 'Ut Picturae Sermones: Homiletic Reflections of Velázquez's Religious Imagery', Arte Cristiana, LXXV/722, 1987, pp. 295-306

-

1988Maclaren, Neil, revised by Allan Braham, National Gallery Catalogues: The Spanish School, 2nd edn (revised), London 1988

-

1993O. Delenda, Velázquez peintre religieux, Geneva 1993

-

1996J. López-Rey, Velázquez: Catalogue Raisonné, Cologne 1996

-

1996M. Clarke (ed.), Velázquez in Seville (exh. cat. Scottish National Gallery, 8 August - 20 October 1996), Edinburgh 1996

-

1997N.A. Mallory, 'Una observación técnica acerca de Velázquez', Goya, 256, 1997, pp. 217-20

-

1998B.N. Prieto, La pintura andaluza del siglo XVII y sus fuentes grabadas, Madrid 1998

-

1998A.E. Pérez Sánchez, 'Velázquez y Zurbarán', Gazette des beaux-arts, 132, 1998, pp. 165-76

-

1998R. White and A. Roy, 'GC-MS and SEM Studies on the Effects of Solvent Cleaning on Old Master Paintings from the National Gallery, London', Studies in Conservation, XLIII/3, 1998, pp. 159-76

-

1999J. Drury, Painting the Word: Christian Pictures and Their Meanings, New Haven 1999

-

1999A.J. Morales, Velázquez en Sevilla (exh. cat. Monasterio de la Cartuja Santa María de las Cuevas, Salas del Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, 1 October - 12 December 1999), Seville 1999

-

2000J.M. Pita Andrade and Á. Aterido (eds), Corpus Velazqueño: Documentos y textos, Madrid 2000

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2001L. Kagané, 'Kartiny Velaskesa Neporocnoe zacatie i Ioann Evangelist na ostrove Patmosa iz Londonskoj nacional'noj galerei', Soobseniâ Gosudarstvennogo Èrmitaza, LIX, 2001

-

2001N. Tromans, 'Un museo en Sevilla en 1822', Goya, 282, 2001, pp. 156-60

-

2002Z. Véliz, 'Becoming an Artist in Seventeenth-Century Spain', in S.L. Stratton-Pruitt (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Velázquez, Cambridge 2002, pp. 11-29

-

2004A.J. Morales and C. Sánchez de las Heras (eds), Symposium Internacional Velázquez, Actas, 8-11 de noviembre, Sevilla, 1999, Seville 2004

-

2005A.E.P. Sánchez et al., Velázquez a Capodimonte (exh. cat. Museo di Capodimonte, 19 March - 19 June 2005), Naples 2005

-

2006D. Carr (ed.), Velázquez (exh. cat. The National Gallery, 18 October 2006 - 21 January 2007), London 2006

-

2007J. Portús, Velázquez's Fables: Mythology and Sacred History in the Golden Age (exh. cat. Museo Nacional del Prado, 20 November 2007 - 24 February 2008), Madrid 2007

-

2008F. Checa, Velázquez: The Complete Paintings, Antwerp 2008

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the series: Two Paintings for the Shod Carmelites, Seville

Overview

Velázquez painted these two works as companion pieces during his early career in Seville, in around 1618. They were perhaps intended to promote the recent celebrations in the city of a papal decree defending the mystery of the Immaculate Conception, the belief that the Virgin Mary was conceived without sin.

We don't know who commissioned The Immaculate Conception and Saint John the Evangelist on the Island of Patmos, but they are first recorded in 1800 in the chapter house of the Convent of the Shod Carmelite Order in Seville.

Saint John and the Virgin both appear in the foreground, surrounded by objects identifying who they are, strongly illuminated from the top left. The colours of the Virgin’s clothes are echoed in reverse in Saint John’s, and both paintings demonstrate Velázquez’s skill in conveying a strong contrast between light and shade.