Diego Velázquez, 'The Immaculate Conception', 1618-19

About the work

Overview

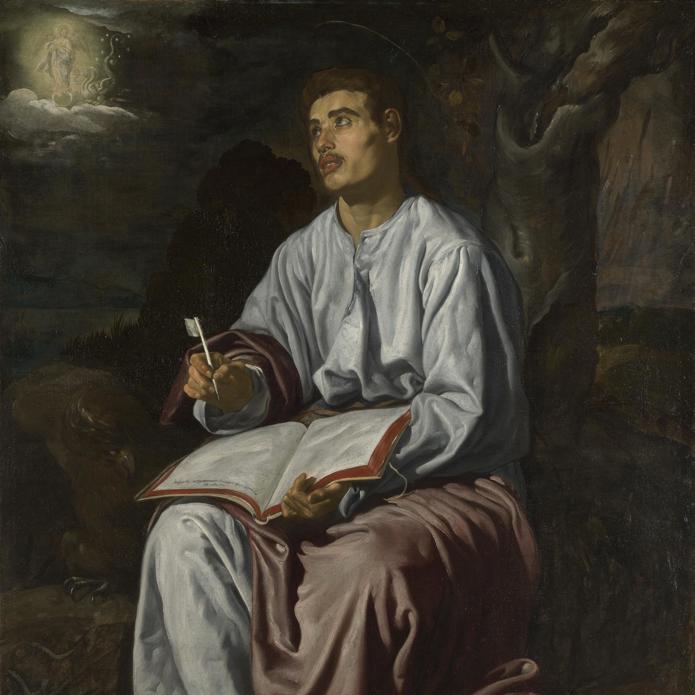

A young woman floats above a landscape, standing on a translucent moon and with a crown of 12 stars. This imagery is based on the New Testament Book of Revelation. In it, Saint John the Evangelist records his vision of the Woman of the Apocalypse, who bears a male child and is threatened by a dragon – the devil.

In the Catholic faith, this woman represents the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ. Her hands are clasped in prayer and she looks down in humility to show her protection over mankind. The garden, fountain, temple and ship at the bottom are all symbols normally associated with her and were included in a litany (or prayer) dedicated to the Virgin.

With its companion painting, Saint John on the Island of Patmos, this is one of Velázquez’s earliest known works.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Immaculate Conception

- Artist

- Diego Velázquez

- Artist dates

- 1599 - 1660

- Part of the series

- Two Paintings for the Shod Carmelites, Seville

- Date made

- 1618-19

- Medium and support

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 135 × 101.6 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought with the aid of the Art Fund, 1974

- Inventory number

- NG6424

- Location

- Room 30

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 16th-century Italian Frame

Provenance

The picture is the same size and of the same date as ‘S. John the Evangelist on the Island of Patmos’ (No. 6264). They are amongst the earliest of Velázquez’s works, certainly painted before he moved from Seville to Madrid in 1623, and perhaps as early as 1618.

The two pictures are first recorded in 1800 as being in the Chapter House of the Convent of the Shod Carmelites at Seville. They were bought by Don Manuel López Cepero, Dean of Seville, who sold them in 1809 to Bartholomew Frere, British Minister at Seville. The pictures were placed on loan at the National Gallery in 1946 by his descendants, Mrs. Woodall and the Misses Frere; the ‘S. John’ was acquired in 1956 and ‘The Immaculate Conception’, with the generous aid of the N.A.-C.F. and an anonymous donation, in 1974.

Additional information

Text extracted from the National Gallery’s Annual Report, ‘The National Gallery: July 1973 – December 1975’.

Exhibition history

-

2009The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600–1700The National Gallery (London)21 October 2009 - 24 January 2010National Gallery of Art (Washington DC)28 February 2010 - 31 May 2010Museo Nacional de Escultura28 June 2010 - 17 October 2010

-

2014Velázquez ExhibitionKunsthistorisches Museum Wien27 October 2014 - 15 February 2015Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais25 March 2015 - 13 July 2015

-

2016Velazquez and Murillo at the Crossroads of SevilleHospital de los Venerables Sacerdotes4 November 2016 - 2 April 2017

-

2020SinThe National Gallery (London)7 October 2020 - 3 January 2021

-

2024The Illustrious GuestGallerie d'Italia - Palazzo del Banco di Napoli23 April 2024 - 14 July 2024

Bibliography

-

1813London, National Gallery Archive, NG72/36/1: Letters about the provenance of NG 6424 by Bartle and George Frere, 1813

-

1981A. Braham, El Greco to Goya: The Taste for Spanish Paintings in Britain and Ireland (exh. cat. The National Gallery, 16 September - 9 November 1981), London 1981

-

1983M. Helston, Spanish and Later Italian Paintings, London 1983

-

1987J.F. Moffitt, 'Ut Picturae Sermones: Homiletic Reflections of Velázquez's Religious Imagery', Arte Cristiana, LXXV/722, 1987, pp. 295-306

-

1988Maclaren, Neil, revised by Allan Braham, National Gallery Catalogues: The Spanish School, 2nd edn (revised), London 1988

-

1992V.I. Stoichita, 'Imagen y aparición en la pintura española del Siglo de Oro y en la devoción popular del Nuevo Mundo', Norba-Arte, XII, 1992, pp. 83-101

-

1993O. Delenda, Velázquez peintre religieux, Geneva 1993

-

1994S.L. Stratton, The Immaculate Conception in Spanish Art, Cambridge 1994

-

1994V.I. Stoichita, 'Image and Apparition: Spanish Painting of the Golden Age and New World Popular Devotion', Res, XXVI, 1994, pp. 32-46

-

1996J. López-Rey, Velázquez: Catalogue Raisonné, Cologne 1996

-

1996J. Pelikan, Mary Through the Centuries: Her Place in the History of Culture, New Haven 1996

-

1996M. Clarke (ed.), Velázquez in Seville (exh. cat. Scottish National Gallery, 8 August - 20 October 1996), Edinburgh 1996

-

1997E. Reeves, Painting the Heavens: Art and Science in the Age of Galileo, Princeton 1997

-

1997L. Kagane, Diego Velázquez: The Immaculate Conception, Saint John the Evangelist in the Island of Patmos, St. Petersburg 1997

-

1998B.N. Prieto, La pintura andaluza del siglo XVII y sus fuentes grabadas, Madrid 1998

-

1998R. White and A. Roy, 'GC-MS and SEM Studies on the Effects of Solvent Cleaning on Old Master Paintings from the National Gallery, London', Studies in Conservation, XLIII/3, 1998, pp. 159-76

-

1999J. Baticle et al., Velázquez, Dossier de l'art 63, Dijon 1999

-

1999A.E. Pérez Sánchez, 'Novedades Velazqueñas', Archivo español de arte, LXXII/288, 1999, pp. 371-90

-

1999A.J. Morales, Velázquez en Sevilla (exh. cat. Monasterio de la Cartuja Santa María de las Cuevas, Salas del Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, 1 October - 12 December 1999), Seville 1999

-

1999H. Brigstocke, 'El descubrimiento del arte español en Gran Bretaña', in Z. Véliz (ed.), En torno a Velázquez: Pintura española del Siglo de Oro, Oviedo 1999, pp. 5-25

-

2000J.M. Pita Andrade and Á. Aterido (eds), Corpus Velazqueño: Documentos y textos, Madrid 2000

-

2000M. Marini, Velázquez, Milan 2000

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2001L. Kagané, 'Kartiny Velaskesa Neporocnoe zacatie i Ioann Evangelist na ostrove Patmosa iz Londonskoj nacional'noj galerei', Soobseniâ Gosudarstvennogo Èrmitaza, LIX, 2001

-

2001N. Tromans, 'Un museo en Sevilla en 1822', Goya, 282, 2001, pp. 156-60

-

2002S.T. Nalle, 'Spanish Religious Life in the Age of Velázquez', in S.L. Stratton-Pruitt (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Velázquez, Cambridge 2002, pp. 110-29

-

2003M. Díaz Padrón, 'Velázquez extramuros: La Inmaculada Concepción, Santa Rufina y las Meninas de Kingston Lacy', in M. Cabañas Bravo (ed.), El arte español fuera de España, Madrid 2003, pp. 208-25

-

2004A.J. Morales and C. Sánchez de las Heras (eds), Symposium Internacional Velázquez, Actas, 8-11 de noviembre, Sevilla, 1999, Seville 2004

-

2005A.E.P. Sánchez et al., Velázquez a Capodimonte (exh. cat. Museo di Capodimonte, 19 March - 19 June 2005), Naples 2005

-

2006D. Carr (ed.), Velázquez (exh. cat. The National Gallery, 18 October 2006 - 21 January 2007), London 2006

-

2007J. Portús, Velázquez's Fables: Mythology and Sacred History in the Golden Age (exh. cat. Museo Nacional del Prado, 20 November 2007 - 24 February 2008), Madrid 2007

-

2008F. Checa, Velázquez: The Complete Paintings, Antwerp 2008

-

2008S. Schroth and R. Baer, El Greco to Velázquez: Art during the Reign of Philip III (exh. cat. Museum of Fine Arts, 20 April - 27 July 2008; Nasher Museum of Art, 21 August - 9 November 2008), Boston 2008

-

2009X. Bray et al., The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture, 1600-1700 (exh. cat., The National Gallery, London; National Gallery of Art, Washington), London 2009

-

2009D. Carr and L. Keith, 'Velázquez's "Christ after the Flagellation": Technique in Context', National Gallery Technical Bulletin, XXX, 2009, pp. 52-70

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the series: Two Paintings for the Shod Carmelites, Seville

Overview

Velázquez painted these two works as companion pieces during his early career in Seville, in around 1618. They were perhaps intended to promote the recent celebrations in the city of a papal decree defending the mystery of the Immaculate Conception, the belief that the Virgin Mary was conceived without sin.

We don't know who commissioned The Immaculate Conception and Saint John the Evangelist on the Island of Patmos, but they are first recorded in 1800 in the chapter house of the Convent of the Shod Carmelite Order in Seville.

Saint John and the Virgin both appear in the foreground, surrounded by objects identifying who they are, strongly illuminated from the top left. The colours of the Virgin’s clothes are echoed in reverse in Saint John’s, and both paintings demonstrate Velázquez’s skill in conveying a strong contrast between light and shade.