Bramantino (active 1490; died 1530)

'The Adoration of the Kings', about 1500

Oil on poplar, 56.8 x 55 cm

NG3073

While many Renaissance architects started as painters, Bramantino designed only one very remarkable building.1 Yet throughout his career he registered a profound engagement with architecture, beginning with the deliberate adoption of the diminutive of Bramante in preference to his own family name, Bartolomeo Suardi. Donato Bramante, Bramantino’s mentor in perspective and architecture, was to become perhaps the greatest of painter-architects. After initial training as a goldsmith, which made him a competent draughtsman, Bramantino (who worked in Milan, visiting Rome in 1508) established himself as a painter, and he gained a reputation as a deviser of perspectival illusions, including designs for intarsie (inlaid woodwork). He also wrote a treatise on perspective and was widely respected as an expert on architecture, if not as a practitioner.

The perspectival scheme

Perspective and architecture are dominant themes in ‘The Adoration of the Kings’. The meticulous perspectival scheme belies the quite free and staccato painting of the figures. This and the fictive architecture prefigure some of Bramantino’s celebrated tapestry designs for The Twelve Months (after 1503, Castello Sforzesco, Milan), and the handling of paint is tighter than in the ‘Madonna of Saint Michael’ (1505, Ambrosiana, Milan). The young king’s head (in profile with long hair to the right) is based upon a famous Roman statue, the ‘Spinario’, described in the poem ‘Antiquarie Prospettiche Romane composte per prospettivo milanese dipintore’ (about 1498), which was probably written by Bramantino himself, and dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci.2

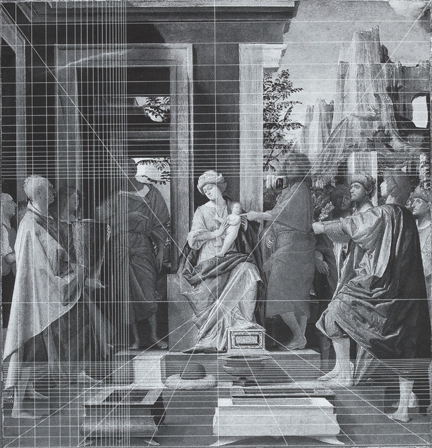

Although the perspectival scheme observable in the incised lines on the surface of the panel – and further revealed by technical examination – follows the rules of Leon Battista Alberti’s ‘costruzione legittima’, this was compromised in the finished painting. A dense net of incised lines setting out a square pavement marks the recession on the left and across the top of the picture, underpinning the architecture and orthogonals (fig. 1).

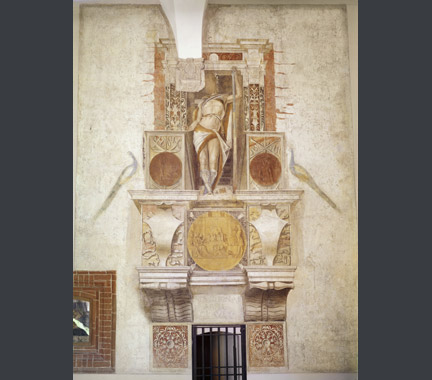

The choice of a relatively low vanishing point (at the level of the Virgin’s lower knee) means there is a substantial foreground, which is filled with three sarcophagus-like chests. Bramantino’s composition recalls Bramante’s ‘Weighing of Gold’ medal below the fresco of Argus above the entry to the strong room in the Castello Sforzesco (fig. 2).3

In the ‘Adoration’ Bramantino reduced the extreme perspectival distortion by placing his figures in a frieze-like arrangement in the middle ground. The edges of the doorways and chests are not precisely set on the perspectival grid, and incisions for the squared pavement are obscured by paint. This willingness to ignore a rigid geometric scheme may give vitality to the building, and it certainly avoided defining precisely where the figures are actually standing. Perspective was used here as a preparatory guide, but did not dictate the final composition of the picture.

This is no straightforward Adoration of the Kings. It includes additional figures that are hard to identify, and an indecipherable inscription imitating Hebrew characters. A prominent figure holding a staff in his hand (probably John the Baptist) points towards Jesus. This reflects the fact that the feasts of the Epiphany and Christ’s Baptism both fell on 6 January, a point stressed in the ‘Golden Legend’. The ruined building is neither the stable of the Nativity, nor a temple like those which often appear in Nativities and Adorations, such as those by Botticelli and Verrocchio. It is a conflation of pale stone cornices and doorways set in a green wall, and probably signifies the old dispensation of Law, in contrast to the new dispensation of Grace represented by the infant Christ.4

Elusive architecture

The building does not appear to have a structural logic. For example, the wall pierced through to the space behind the figures appears improbably deep. The door frames have simplified, flattened curves instead of the usual S-moulding at the outer edge, and the normal curved beading in the centre of the frames has been replaced by a simple right angle. These forms, while unprecedented in doorways, are common in entablatures. Bramantino explored the curved profile in the broken cornice and door moulding in a pentimento in the upper centre. The play on curves continues in the gifts, the chests and the beaky noses of the kings and their attendants.

There are echoes of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’ (1495–8, Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan) in the use of doors and openings to frame a view beyond. The precipitous landscape provides further architectural opportunities. The dominating mountain was originally conceived as a castle with great towers, as X-rays reveal. The ruined triumphal arch in the distance is something of a novelty in Milanese painting and the little tower seems taken directly from the central panel of Pietro Perugino’s altarpiece for the Certosa of Pavia (1496–1500, The Virgin and Child with an Angel, NG288.1), a work that was responsible for a major change of direction in Milanese painting.

Charles Robertson

Selected literature

Suida 1953, pp. 67–8; Davies 1961, pp. 128–9; Dunkerton 1993; Morale 2004; Agosti, Stoppa and Tanzi 2012, pp. 37–9.

This material was published in April 2014 to coincide with the National Gallery exhibition 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting'.

To cite this essay we suggest using

Charles Robertson, ‘Bramantino, The Adoration of the Kings’ published online 2014, in 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting', The National Gallery, London, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/architectural-time/bramantino-adoration-of-the-kings