Author: Amanda Lillie

1. Introduction

In his ‘Life of Brunelleschi’ Antonio di Tuccio Manetti provided the only 15th-century description of two painted panels by Brunelleschi showing perspectival representations of the Florentine Baptistery and the Piazza Signoria.1 In this key account of the mathematical construction of pictorial space, the word space (‘spazio’) never occurs. Instead, a set of key terms alerts us, on the one hand, to the linked concepts of ‘regola’, ‘misura’ and ‘ragione’ (the systematic application of scale, measurement and proportion that establish the mathematical and theoretical framework of perspective), and on the other hand to the notion of the image as a ‘portrait’ (‘ritratto’) of the ‘place’ (‘luogo’).2 This activity of portrait making is emphasised by the use of phrases such as truth (‘proprio vero’) and testimony (‘possone rendere testimonanza’).

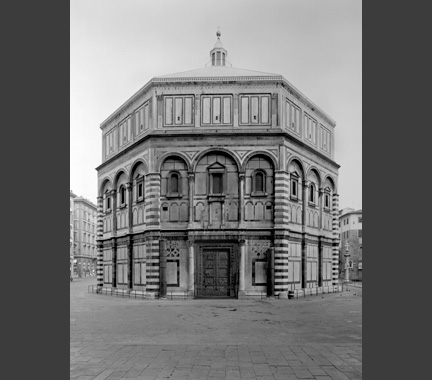

Reality and representation merged in the nature of the Baptistery panel itself, which was both a mirror and a painting, with buildings that were drawn against a background coated in burnished silver to reflect the actual sky.3 This was a portrait of a specific and (for Florentines) an immediately recognisable place (fig. 1) in which the buildings seemed to be portrayed (‘ritratto’) in the real air, and the winds carried the clouds across the reflected sky, animating the whole picture. The passage brings to the fore the crucial concern of how to represent place, how to make it look real and establish its particular identity. It could even be argued that the main purpose of Brunelleschi’s perspective panel was to demonstrate a new way of depicting place (‘il luogo’), and that perspective was the tool or the means, rather than an end in itself (as the 20th century usually interpreted it).

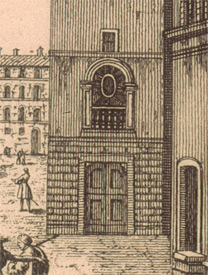

Although working on a smaller scale than architects, painters played a fundamental role in constructing real places and in creating and disseminating the identity of places through their images. Mural paintings in particular literally became part of a place, and the interaction between image and site profoundly affected the way each was perceived. Thus, the placing of Domenico Veneziano’s frescoed ‘Madonna and Child’ (fig. 2) above a Florentine street corner helped to redefine that site – the Canto de’ Carnesecchi – and gave the Carnesecchi’s house where the tabernacle was placed a new name: ‘la chasa della Vergine Maria’.4 At the same time, the positioning of the Virgin’s tabernacle was chosen because it was at a strategic junction of three streets and on a ceremonial route between the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore and the Dominican Priory Church of Santa Maria Novella.5 This particular piece of wall was a prime tabernacle site since it enjoyed greater public exposure than any other surface on that route. The wall directly faced the north corner of the Cathedral façade from a distance of about 200 metres, addressing all who approached down the Via de' Cerretani, one of the busiest streets in the city (fig. 3). The tabernacle was probably placed high up so as to be seen above the crowd during religious processions (fig. 4).

This route was of special significance in 1439, when the ecumenical Council of Florence was meeting at Santa Maria Novella, and indeed during the whole time Pope Eugenius IV was resident in Florence, when there would have been frequent to-ing and fro-ing as well as processions between the Cathedral and the Dominican priory where the Pope lodged.6 The site was also on another processional route going along the Via Tornabuoni from the Cathedral and Via de' Cerretani. The mutual benefits are clear. The tabernacle enhanced and sanctified the site, while the power of the image was immeasurably increased by its public exposure, its incorporation into processional routes and its association with the 1439 Council meetings in Florence. Domenico Veneziano responded to the site by designing a strictly frontal pose for the Virgin and Child, directly facing the street, with the Virgin holding up Christ to balance him at the very end of her knee, as close to the public as possible, and above all by determining the infant’s gesture, so that Christ blessed all who walked down the street (fig. 5).

It may be hard to imagine when encountering the dislocated and much restored remains of Domenico Veneziano’s Carnesecchi Tabernacle that this work once had street power and a defined ceremonial and religious purpose. Yet because it is damaged, weather-beaten and fragmentary, it can speak to us as a brave survivor and stirs a different set of emotions. As archaeologists well know, ruins and fragments are often more powerful reminders of what buildings or objects once were than pristine, new-looking things. They plot the passing of time, and in this case make us aware of the 575 years between the making of this picture and our standing before it. The condition helps us to re-imagine it as a site-specific work, exposed to the elements, high up on the east-facing, narrow end of a block. The painting still retains some of its essential aesthetic qualities. Its surface may be damaged beyond retrieval, but its architectonic, geometric and volumetric qualities are still legible; as is the Virgin’s still solemnity and God’s gesture – throwing his arms forwards to launch the dove of the Holy Spirit and at the same time present to us the Virgin and Child.

Read further sections in this essay

- 2. Between real and imagined places

- 3. Between street and piazza: The Florence of Saint Zenobius

- 4. Imagining the Temple in Jerusalem: an archetype with multiple iconographies

To cite this essay we suggest using

Amanda Lillie, 'Entering the Picture' published online 2014, in 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting', The National Gallery, London, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/place-making/introduction