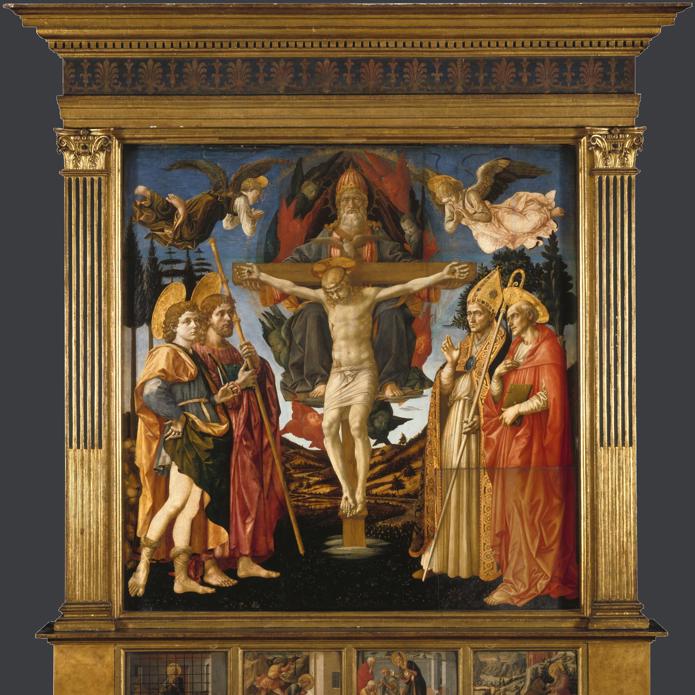

Francesco Pesellino and Fra Filippo Lippi and workshop, 'The Trinity', 1455-60

About the work

Overview

This large pala (an altarpiece with a single, unified surface) was painted for a church in Pistoia but was sawn into pieces in the eighteenth century; most of it was later reassembled in the National Gallery. Look closely and you can see lines where the separate fragments were put back together.

It shows the Trinity: God the Father floats in mid-air, holding up the Cross, Christ’s body hanging on it; the dove of the Holy Ghost hovers between them. The altarpiece was commissioned by a confraternity of priests dedicated to the Trinity – hence the subject.

The painting was begun by Francesco Pesellino and completed after his death in 1457 by Fra Filippo Lippi. It was described as ‘half finished’ when Pesellino died and we're not completely sure which bits were done by which artist.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Trinity

- Artist

- Francesco Pesellino and Fra Filippo Lippi and workshop

- Artist dates

- 1422 - 1457; born about 1406; died 1469

- Part of the group

- The Pistoia Santa Trinità Altarpiece

- Date made

- 1455-60

- Medium and support

- Egg tempera on wood

- Dimensions

- 185.5 × 91 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1863

- Inventory number

- NG727

- Location

- Room 60

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Previous owners

- Frame

- 20th-century Replica Frame

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Dillian Gordon, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings’, vol. 1, London 2003; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2023Pesellino: A Renaissance Master RevealedThe National Gallery (London)7 December 2023 - 10 March 2024

Bibliography

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2003Gordon, Dillian, National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings, 1, London 2003

Frame

This is a twentieth-century reproduction frame, made by an unknown workshop in Paris. Constructed in pine with water gilding, the altar frame features pilasters with gilt-stopped fluting in blue and gold, crowned by Corinthian capitals. The entablature, with an intricately painted frieze in gold and blue, showcases palmetto motifs.

The creation of the reproduction frame was arranged in 1929 by the art dealer Joseph Duveen (1869–1939). It replicates the frame that originally housed The Holy Trinity by Donnino and Angelo di Domenico del Mazziere, in the Church of Santa Spirito, Florence. Hidden ornaments lie underneath the loaned panels.

The reproduction predella frame was crafted at the Gallery in the 1990s to house four individual panel paintings. It was constructed with vertical divisions and water-gilded to match the altar frame.

The altar frame of the original Pistoia Santa Trinità Altarpiece was lost when its panel was cut into pieces in 1783.

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the group: The Pistoia Santa Trinità Altarpiece

Overview

This large altarpiece – one of the few in the National Gallery which is almost complete – has had an eventful life. It was commissioned in 1455 from the Florentine painter Francesco Pesellino, and is his only surviving documented work. He died in 1457 and it was finished by Fra Filippo Lippi and his workshop. We know a lot about how and why it was made from the records of the confraternity who commissioned it.

From 1465 it sat on the high altar of the church of the Holy Trinity at Pistoia, but in 1793 the confraternity was suppressed and the altarpiece was taken apart, with the main panel sawn into pieces, and dispersed. Most of it was gradually acquired by the National Gallery and the altarpiece reassembled.

This is the earliest pala (an altarpiece with a single main panel) in the National Gallery.