Episode 57

The National Gallery Podcast

Grayson Perry on the Sainsbury Wing. Plus exhibition previews: ‘Devotion by Design: Altarpieces before 1500’ and ‘Forest, Rocks, Torrents’.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): This is the National Gallery Podcast and I’m Miranda Hinkley. In this month’s episode...

‘Forests, Rocks, Torrents’ – a new exhibition of Norwegian and Swiss art brings some stunning and rarely exhibited landscapes to London.

And artist Grayson Perry tells us why he’s so fond of the Gallery’s collection of early Renaissance art.

But we start with our latest exhibition, ‘Devotion by Design.’ Part of a new series of shows focussing on the permanent collection, ‘Devotion by Design takes a fresh look at the Gallery’s exceptional collection of Italian altarpieces from the 13th to 15th centuries. In addition to revealing new research, the show also promises to display these often magnificent objects in ways that may come as something of a surprise. Leah Kharibian went to investigate.

Leah Kharibian: It’s not long before the exhibition, ‘Devotion by Design’, opens to the public on 6 July and to show me some of the preparations being made, the exhibition’s co-curator, Jenny Sliwka has brought me up to the Gallery’s conservation department. Jenny, what is it that we’re seeing here?

Jenny Sliwka: Well, this is quite exciting... this is Pietro Gerini’s ‘Baptism Altarpiece’ which was painted in 1387 and I wanted to bring you up here to show you the work that we’ve been doing on the altarpiece. It’s been up here for just over a year and a half.

When we first examined it we made quite a few exciting new discoveries and since then it has also been cleaned and restored. And it’s actually quite unusual – it’s one of the first examples that we have of a baptism that is a narrative scene as the central panel. That’s the place that as you know you would normally expect to see the Virgin and Child, or one particular standing saint. So it’s a very special moment in the history of art actually as well...

Leah Kharibian: And so we have Christ in the centre being baptized by Saint John the Baptist and then two saints to either side in this very elaborate frame. Is that all original?

Jenny Sliwka: Actually, it’s not... it’s very deceptive. It’s a close approximation of what we might have seen in the 14th century but it’s entirely 19th century. There are some original bits and bobs, so it’s actually been pieced together in the 19th century when it was in a Florentine collection just before we purchased it for the Gallery.

Leah Kharibian: But bringing it up to Conservation... what have you been able to find?

Jenny Sliwka: Well, before we even started cleaning it, we discovered a curious metal bar along the base of the central panel below the baptism, which just did not fit with anything we know about Renaissance painting. So we removed it and lo and behold we discovered an inscription... an inscription that someone had, at one point, recorded having seen, but we thought we had lost it forever. And we rediscovered it, so it’s kind of an art historian’s dream. It said who the altarpiece had been made for – that is, the patron – and it also had the date. That’s why we know precisely it was painted in 1387 now.

Leah Kharibian: That’s absolutely fantastic. Now I know this exhibition promises to display altarpieces in ways that will be quite unlike the visitors’ usual experience of seeing altarpieces in the Gallery and I wanted to know in particular, what were your plans for this Gerini?

Jenny Sliwka: It’s quite exciting. The way we will see the Gerini in the exhibition is very different to how we will see it hear in the conservation studio, under bright natural light. It will be installed in a room that will evoke a Tuscan church circa 1500, so it will actually be going back in time, and it will be placed on an altar in very low lighting and some of the light that it might pick up is the flickering of candles.

We’re actually going to have a particular kind of candles, not real candles, in that room, and the candles will pick up on the gold, of course, but different aspects will fade away and different aspects will reveal themselves, I think, in this darker lighting... much more akin to how it would have been viewed in the 14th and 15th centuries, I think. And what might come out are these beautiful glowing colours which have now been revealed after the year and a half of cleaning that it’s had in conservation. These sort of rainbow colours... and quite acidic yellow and greens as well, which people, I think, don’t necessarily think of when they think of a 14th century painting. It’s almost a firework display in some cases.

Leah Kharibian: That sounds as if it’s going to be really beautiful. But this evocation of a church setting gets right to the heart of what this exhibition is really trying to do, isn’t it? That is, set these altarpieces in context.

Jenny Sliwka: Absolutely. I mean, we forget sometimes, walking through a gallery, appreciating these works as works of art, that they were created as focuses for devotion – they’re devotional objects. And so putting them back into context, you can imagine the rituals – the high mass – that were conducted in front of them... and the miracles that purportedly happened in front of them as well. It’s an idea of reconnecting to their original function.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Jenny Sliwka talking about the ‘Baptism Altarpiece’ by Gerini. If you’d like to see the work for yourself, ‘Devotion by Design: Italian Altarpieces before 1500’ opens at the Gallery on 6 July. Admission is free.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Next... The celebrations continue for the 20th anniversary of the Sainsbury Wing. Opened in 1991, this extension to the Gallery’s main building in Trafalgar Square houses our collection of early Renaissance art. From glittering gold altarpieces to highly detailed portraits there’s plenty to study and enjoy, which is perhaps why, when asked to choose his favourite work in the National Gallery, the artist Grayson Perry answered: ‘the Sainsbury Wing’. Colin Wiggins from the education team took a walk with him around the rooms...

Colin Wiggins: So Grayson, what is it about the Sainsbury Wing and its difference from the more traditional part of the Gallery that attracts you?

Grayson Perry: When I think of my own relationship with art history, my first contact with it was at school art lessons. And the book we had was called ‘Giotto to Cezanne’. And I can remember hating all those early paintings when we first saw them, and I’d say, ‘they’re rubbish, they can’t draw properly,’ because when you’re however old I was at the time, 13 or 15, you’ve got an empirical view of what painting is. And so it’s how realistic it is, basically, so all you like really is Salvador Dali and kind of photorealism and album covers and then... now of course, here I am, sort of 35 years later and my love is the early period – you know, the early Italians and the Flemish painters – and it’s very much just the very fact that they’re not in some ways super-real is why I like them.

Colin Wiggins: Yeah, we’re right at the beginning of the Sainsbury Wing here and of course what it’s meant to do is tell a story, from this idea that art develops and evolves and that these are the kind of artists that a hundred years ago would have been described as primitives.

Grayson Perry: The thing I like is the density and the kind of jewel-like quality of the smaller work. You know, their presence as an object is very strong and you really feel like you could... I mean, some of them are literally standing up in the middle of the room and often with the great Titians and Gainsboroughs and paintings like that, I kind of... I mean, I love them in a book and then when I see the actuality of them they feel like slightly sort of dusty stage sets sometimes – you know, all the drapery and angels and the fact that it’s a bit of cloth. You know, as a sculptor it’s unsatisfying to me sometimes.

Whereas when you go into here and you’ve got ancient things – objects, they’re very much objects – suddenly they’re isolated on the bare walls and they’re on wood and they’re icons and you can almost feel yourself picking them off the wall, and the fact they’re carried around in baggage trains throughout history. And that’s what I really like about them, you know, as a maker of objects, who has a sensitivity to texture and the kind of, almost possessable quality of things. You’re in an area where a painter is as much a craftsman as an artist and so therefore he will be aiming at a kind of... something that he would have learnt... he wouldn’t be expressing himself. He would be perfecting a craft and a craft is a depiction and they were kind of wrestling with that craft at the time. And that’s what I like about it... is that they tried to do... they might have not had the kind of effects and tools of later artists, but they did have the time and the skill.

Colin Wiggins: Yeah, the craft aspect of the Sainsbury Wing pictures is to a contemporary audience fairly astonishing and that’s something that in a way we kind of kissed goodbye to at the beginning of the 20th century, when Picasso and Braques start cutting up old newspapers and gluing them onto bits of old sack and Duchamp starts showing bicycle wheels. And craft in the 20th century, with one or two exceptions, just goes out the window. So it’s fascinating I think for a contemporary audience to just see what art used to be about. And do you regret in a way that contemporary art has lost that craft, that skill aspect?

Grayson Perry: To me sometimes, I look at a lot of contemporary art and I just see them as quite badly done illustrations of not particularly interesting ideas, and that kind of relationship with the material and that kind of dual-track idea where you’ve got great skill and great sort of imagination and creativity. I mean there are lots of artists who are bad craftsmen and there are lots of craftsmen who are really bad artists... there are very few that are both. And I don’t necessarily put myself in that... I always say I’m a conceptual artist masquerading as a craftsman. But when I look at the paintings in this Sainsbury Wing, I kind of still see this kind of golden age... you can imagine these people belonging to guilds...

Colin Wiggins: Which they did...

Grayson Perry: And that for me is a satisfying thing.

Colin Wiggins: And they had to qualify for their guilds. I mean, it took a long time to train before the guild would have you, before you were allowed to sign pictures and sell your own pictures and take pupils and things. It was all incredibly regulated. It’s also of course just the chance of survival, because just about 2% of pictures from this period survive.

Grayson Perry: These are amazing survivors and I think that’s a recommendation to their power as objects that they were protected, through all different kinds of societies that would have had different values. You know they never were kind of discarded as irrelevant. That’s what I like about the art in the Sainsbury Wing.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Grayson Perry, talking to Colin Wiggins.

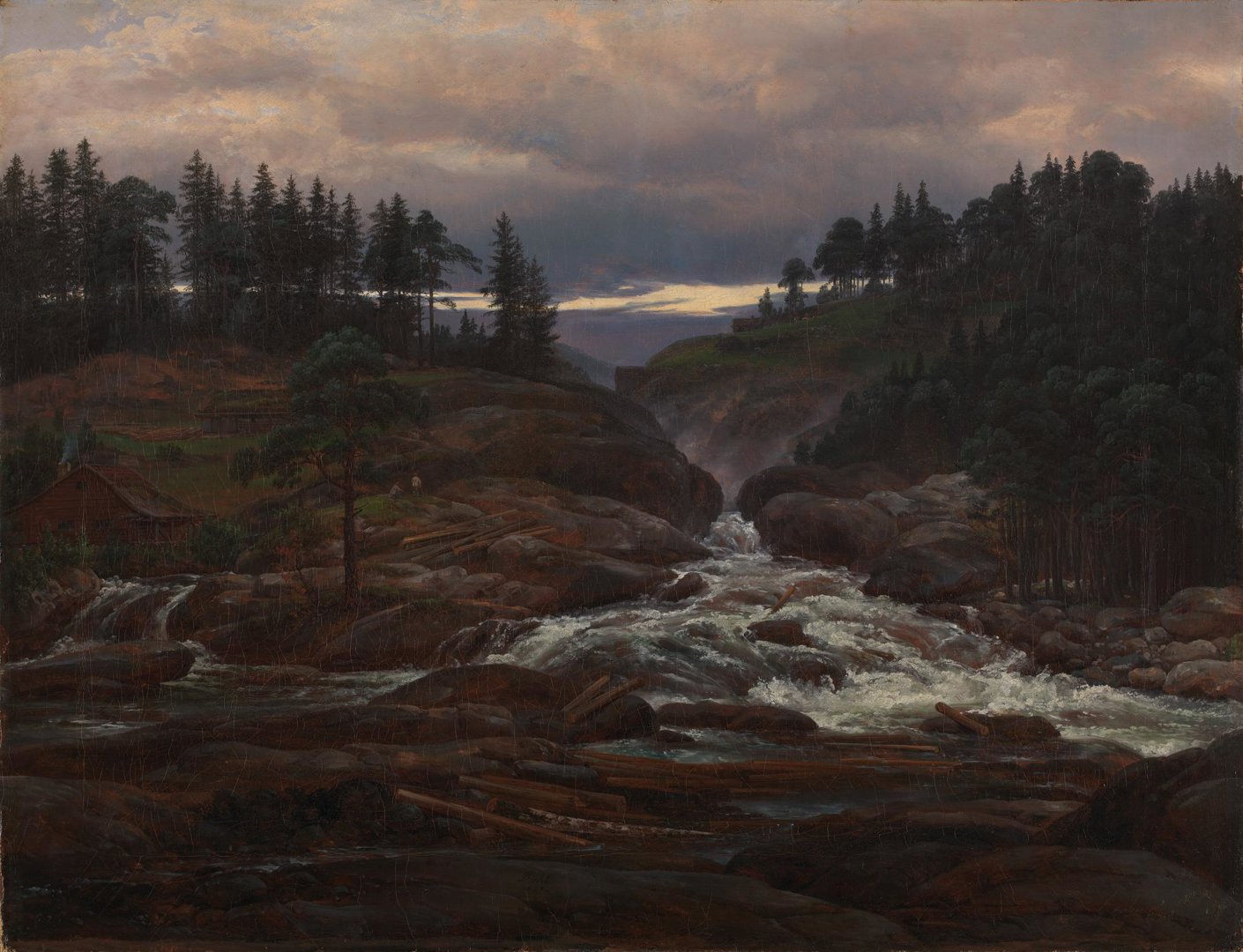

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): And now to a fascinating exhibition currently on show in the Gallery’s Sunley Room. It’s called ‘Forest, Rocks, Torrents and it brings a group of works to London that is rarely, if ever, shown in public. The pictures come from a private collection gathered over many decades by a New York lawyer, Asbjørn Lunde.

They highlight the dazzling achievements of landscape painters from two countries we might not readily associate with great 19th-century art – Norway and Switzerland – and also reveal the aspiration they shared to found a national identity through their work. Leah Kharibian met curator Chris Riopelle in front of the pictures as the exhibition was being hung to find out more.

Leah Kharibian: Chris I have to say that these works are a real surprise. I mean they’re absolutely spectacular and you’ve brought me to one in particular – a landscape by Johan Christian Dahl, ‘The Lower Falls of the Labrafoss’. And I was wondering if you could begin by describing it for me and also by saying why it is that this picture begins our story?

Chris Riopelle: This painting of 1827 is an early masterpiece of Dahl’s in which everything he wanted to say about the rugged Norwegian landscape is there. We’re looking at a waterfall tumbling out of the hills, out of the trees, straight at us and carrying with it logs from a lumbering industry – they pour over the rocks at the bottom of the falls. Everything that is difficult, inaccessible, isolated, but also rich in natural resources about Norway is here.

Leah Kharibian: It’s absolutely beautiful but I suppose the question that springs to mind is, why does Norway need a national school of landscape painting?

Chris Riopelle: The Norwegians were not alone in using landscape to think about themselves, to think about what their lives were like, how they related to landscape. But because the conditions in Norway were so severe, landscape painting there took on a particularly dramatic edge.

Leah Kharibian: Severe in what way? The weather? What are we talking about?

Chris Riopelle: The weather... the isolation of the motifs that these artists were painting, the minimal population... indeed, the poverty. Norway in the early 19th century had no political independence, was extremely poor, relied on the export of natural resources and so to decide to depict that landscape with such pride was a statement of ambition for their country.

Leah Kharibian: That’s absolutely fascinating. So do you feel that landscape has this capacity to be emblematic of a national spirit in a way that other genres don’t quite manage?

Chris Riopelle: I think that that was one of the great aesthetic discoveries of the late 18th/early 19th century, that yes, landscape when it was your landscape could somehow become deeply expressive of who you were as a nation, as a people.

Leah Kharibian: This exhibition is not only about Norwegian landscape painting, but also landscape painting in Switzerland, which is again another real eye-opener and I was wondering if we could go to perhaps the most spectacular picture in the whole show...

[Footsteps]

This is just wonderful. I mean, this is torrents with knobs on, isn’t it really? It’s by Alexandre Calame and it’s called ‘Mountain Torrent before a Storm’ and it really is spectacular.

Chris Riopelle: Calame, who was the great Swiss painter of the 19th century and in the 19th century one of the most famous painters in all of Europe, one of the most expensive painters in all of Europe, he was absolutely adored. This picture that we’re looking at went straight from Switzerland to the collection of Prince Yusupov in St Petersburg.

Leah Kharibian: Wow. So why is it then that we haven’t heard about these guys – I mean, they’re all amazing!

Chris Riopelle: It is the fate of many of the leading artists of the 19th century – so great was the impact of impressionism and later modern styles, that a whole tradition of academic painting of the greatest technical skill has been forgotten by most of us.

Leah Kharibian: Right, and so when you look at works like this, which – I mean, it’s wonderful to have this collection here in the National Gallery – does it affect the way that you then look at the permanent collection that’s here?

Chris Riopelle: It certainly does. Our permanent collection of modern pictures has been traditionally very biased toward the avant-garde, toward French Impressionism and the movements that came after it. This reminds us that there was a whole other tradition of the most extraordinary completeness and vividness living at the same time. We have historically made a choice, but the other side is still there and slowly perhaps we’ll come to appreciate it, too.

Leah Kharibian: Yes, it really is a must-see, I think. A real, real eye-opener. Thank you so much.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Thanks to Chris Riopelle. You can visit the ‘Forests, Rocks, Torrents’ exhibition in the Sunley Room at the National Gallery until 18 September. Admission is free.

That’s it for this episode. Don’t forget you can take a look at any of our paintings online at www.nationalgallery.org.uk, where you’ll also find information about upcoming exhibitions and events, including this November’s major show: ‘Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan’.

Until next month, goodbye.