Episode 20

The National Gallery Podcast

In the June 2008 podcast, Jon Snow tells us about his fascination with Lake Keitele, Dave Brown on reinventing famous paintings and an introduction to the exhibition Radical Light.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Hello, I’m Miranda Hinkley and this is the National Gallery Podcast. Coming up this month: Italian painters experiment with radical art and politics in a major new exhibition opening this month, Channel Four newsreader Jon Snow makes his vote count as a National Gallery trustee, and…

Dave Brown: As in Holbein’s version the objects really tell the story, so it’s all the topics they were talking about, so we have a NATO helmet, a flask of rather dodgy looking nuclear material glowing rather dangerously, and the nude photo of Carla which was on auction in New York at the time, and on it, on the corner, Sarkozy’s hung his Aviator sunglasses and his big bling Rolex watch.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Political cartoonist Dave Brown reimagines Holbein’s masterpiece, The Ambassadors, for the 21st century.

Coming soon: ‘Radical Light: Italy’s Divisionist Painters 1891 – 1910’

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): We start though with the National Gallery’s latest exhibition. The question of how to capture the play of light has long fascinated artists, and few have been as successful in the attempt as those associated with Italian Divisionism. In the last decades of the 19th century, these artists experimented with painting techniques in a bid to flood their canvases with light, and the results still dazzle today. The Radical Light exhibition offers a unique chance to see a group of these luminous works in one place, and explores the equally radical political agendas that fuelled their creation. Leah Kharibian spoke to curator Chris Riopelle to find out more.

Chris Riopelle: Divisionism is a term very much associated with this group of Italian artists at the end of the 19th century. They had decided that the great theme of modern painting would be light and so they set themselves the problem, how do you bring light into a painting in new ways? And their answer was that you do it by dividing up colours on the canvas itself. That is to say, instead of traditionally mixing colours on your palette and then applying them to the canvas, you put pure colours onto the canvas in divided brushstrokes, so you would have green next to red next to blue.

Leah Kharibian: That sounds to me a little bit like French Pointillism, the technique of painting in dots of pure colour that was developed by Seurat and other artists like Signac. Are Italian Divisionist painters taking inspiration from the Pointillists, or are they different?

Chris Riopelle: The Italian Divisionists were hearing about this experimental painting going on in Paris where painters like Seurat and Signac were painting with dots of pure colour. They had never seen any of these works – they only had descriptions of them, but they realised that rather than using dots, by using these lines or filaments of colour, pure colour, they could achieve some of the effects that they knew the French Pointillists were achieving.

Leah Kharibian: Using these sort of threads of colour rather than dots or points, there’s a wonderful painting by Angelo Morbelli called ‘For Eighty Cents!’ which shows women who are picking out the weeds in the rice fields with their ankles in the water. It seems that he, like many other Italian painters, are allying this new technique also with a deal of social comment.

Chris Riopelle: There is a political dimension, very strongly, in Divisionism as there was in Pointillism. Both in France, and in Italy, the artists were hoping that their art could make a difference in society… could lead to social transformation. There is a big difference between the two, however, in that the French painters tended to be anarchists, tended to want to see the overthrow of the traditional organisation of society. In Italy, the artists who were very involved in radical politics, were not anarchists, they were socialists.

Leah Kharibian: This idea that a painting technique – obviously allied with a particular type of subject matter… but that a painting technique like Divisionism can somehow be an instrument for social change – that, you know, art can emancipate people, that it can be part of a social progress, I mean isn’t that a bit nuts?

Chris Riopelle: Well, when you take as your great theme in painting, light – light traditionally has a great range and spectrum of meanings. It’s not only about colour, it’s also about enlightenment – it implies the bringing of new knowledge to bear on situations and so by focusing on light and how you bring it into paintings, they were also focusing on the possibility of political enlightenment at the same time. So there is in much Divisionist painting a kind of… even in the most realistic depictions of social problems there is kind of an allegorical dimension built into it, if you will – an aspiration to improve society by doing this.

Leah Kharibian: All these ideas seem to feed into a group of artists who came to call themselves the Futurists, and I know that the exhibition ends with a fantastic group of works of the Futurists just at the moment when the Futurist manifesto which came out in 1909 was published. And there’s one in particular that I thought we could talk about, which is this Luigi Russolo, called ‘I Lampi’, which has this fantastic contrast between a great strike of lightening coming down on Milan, the newly built Milan, and the streetlamps which are glowing in the dark. It’s evening time. I wonder if you could talk us through what it was for the Futurists that attracted them to Divisionism.

Chris Riopelle: There’s something quite fascinating in avant-garde art in Italy at this time. Whereas in France and most other places avant-garde art was a series of radical breaks with the past, overthrowing everything that had come before, in Italy, you see a direct growth of Futurism out of Divisionism. The Futurists always said that it was the Divisionists who first showed the way to a modern art, and so they always honoured that generation that had come before them… saw that the depiction of light and the depiction of social problems gave them – the Futurists – a basis on which to build an even more radical and even more audacious art that broke with the conventions, that would break with the conventions of naturalistic representation.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Chris Riopelle. And if you’d like to see those extraordinary light effects for yourself, come along to the exhibition; it opens on 18 June and tickets are available from the Gallery or online with a booking fee. And you can hear more from curator Chris Riopelle on the exhibition audio guide.

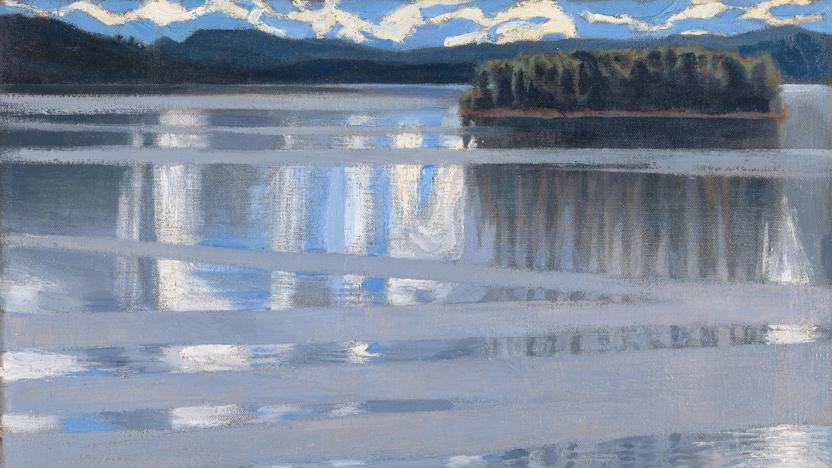

Jon Snow on Gallen-Kallela’s ‘Lake Keitele’

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): The subject of our next interview is best known for his long tenure as the plain-speaking, down-to-earth front man of Channel Four news. Less well known, perhaps, is that for the past eight years, Jon Snow has also served as a trustee of the National Gallery. I asked him about his love affair with one particular picture when I spoke to him in the Gallery.

Miranda Hinkley (in the Gallery): I’ve come to have a closer look at a painting by the artist Gallen-Kallela, who’s from Finland. It’s called Lake Keitele, and I’ve come to look at it because it’s the favourite painting of one Jon Snow. Jon, what is it about this work that you like so much?

Jon Snow: Well, I think in the end it’s one of the most different pictures in the National Gallery for a start – it stands out. It seems to have a natural affinity with Impressionism, Pointillism, but it is in fact… I suppose you’d call it a European Expressionist painting. The thing is the more you look at it, the more you see, which is of course true of so many paintings, but it’s about something very deep and spiritual – there’s something very moody about it, and yet it’s also technically very exciting. I mean, I love the very broad brushstrokes that float across in a very, very determined way to lend the picture its perspective. I think the sky is interesting in the extreme and as is its reflection in the water. But I think above all it’s the looming presence of this island in the right-hand top end of the picture, which is both dark, mysterious, brooding, but somehow enticing too – you’d like to know what goes on there.

Miranda Hinkley: I think the more you look at it, the more you realise that it stands out from everything in the Impressionist room, but you also have a very personal connection to this work, don’t you?

Jon Snow: Well, I do, because I was a trustee from 1999 – the year we bought it – and a very shy one actually. I mean, when you arrive at the National Gallery as a trustee, you feel you’re the most ignorant man in the Gallery, which I still remain. And I’ve just finished being a trustee, and I count this as being something where I really made a contribution, because in the end, we had to decide whether to buy it or not and of course there were people who really were very well equipped to give an account of a picture and there were people who were able to make a very informed judgement about it. I was neither of those things. I merely looked at it as something… would I like to have it in the Gallery? Would it enhance the Gallery? Would it be something that people would enjoy and I thought positively absolutely, and I was the swing vote, so I like to think that I was part of getting it.

It’s interesting because there are very, very few of this guy’s paintings outside Finland, almost none at all and this came up in New York and it was a one-off chance to have it, and I believe that since we’ve had it, it’s been a fantastically well selling postcard, so that indicates that we got it right to some extent. If public joy at the picture is anything to test it by…

Miranda Hinkley: Jon, you’ve been to… you’re very well travelled, you’ve been to some difficult situations, you’ve covered war zones – what does the Gallery mean to you? Is it somewhere where you come and get away from all that and relax or does it speak to what you do in some way?

Jon Snow: I think you think you’re coming in here to escape the world outside and I always saw it initially as something which gave me breathing space from the world outside, from the world that I had to intersect with, but of course, the longer you spend in here, the more you find yourself reconnecting with some of the issues – particularly religion – that you thought you’d left outside.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Thanks to Jon Snow. And if you’d like to see ‘Lake Keitele’ for yourself, come along to the Gallery – it’s currently on display.

Dave Brown reimagines ‘The Ambassadors’

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Dave Brown’s cartoons for the ‘Independent’ newspaper have won him acclaim as a funny and incisive chronicler of British political life. Sketches in his ‘Rogue’s Gallery’ series, published every Saturday, offer judgement on the politics of today by pastiching great paintings from the past. Over the years he’s pressed many National Gallery pictures into service, including Holbein’s The Ambassadors, much loved by visitors for its mysterious image of a skull which blurs in and out of focus depending on where you stand. Cathy Fitzgerald went to meet Brown and began by asking how his version of the painting differs from Holbein’s.

Dave Brown: My version of ‘The Ambassadors’ is done at the time of Sarkozy’s visit to Britain for a state visit. So we have Gordon Brown standing in the rather fine Tudor dress and Sarkozy on the other side and they’re leaning on the shelf as in Holbein’s version with an array of objects between them, and as in Holbein’s version the objects really tell the story, so it’s all the topics they were talking about, so we have a NATO helmet, a flask of rather dodgy looking nuclear material glowing rather dangerously, and the nude photo of Carla which was on auction in New York at the time, and on it, on the corners, Sarkozy’s hung his Aviator sunglasses and his big bling Rolex watch.

Sarkozy is supposedly a great fan of Thatcherism and the Anglo-Saxon way of doing things, so there’s the bust of Thatcher on the bottom shelf, slightly worse for wear, the tip of the nose is broken off, and next to that we’ve got the atlas open at Afghanistan. Sarkozy had just committed troops to Afghanistan, to the war. And one of the other issues they were talking about was the European Union, so I’ve made it quite literally a political football; it’s a football in the blue and yellow colours of the EU flag. At the bottom, we’ve got this strange object, which it isn’t really apparent immediately what it is, and as in Holbein’s it’s a skull – it’s a memento mori, a reminder of death, but of course in my version, death is Bush.

Cathy Fitzgerald: So it’s George Bush at the bottom – how did you get the skull effect?

Dave Brown: Yes, I’m sure Holbein must have used some sort of technology of his day to draw the anamorphic skull, whether it was a camera obscura or a glass cylinder or some sort of perspective drawing frame. But now, of course, I had Photoshop to do it, so I drew a little sketch in normal perspective of Bush as a skull, trying to get it as skull-like as possible, but also keep the likeness. Then scanned it and put it in Photoshop on the computer, and using the distort tools you could stretch it to the desired shape. And then print it out and copy that down on to the final cartoon. Because I wanted to make sure that, as in the original, you could look down the side of the picture and see the skull come back into the proper perspective.

Cathy Fitzgerald: And what’s up in the top left-hand corner? In Holbein’s painting there’s a small silver crucifix that just peeps through on the top left – what have you got?

Dave Brown: Yes, instead of the crucifix, there’s half hidden an old black and white photo of Blair. So it’s the icon of the old religion half hidden behind the curtain and gathering dust.

Cathy Fitzgerald: You’ve based your cartoons on pictures for a number of years. What is it about paintings that draws you back as a source of pastiche?

Dave Brown: Well, I think with very well known pictures it’s an easy way in for the viewer. If it’s something they recognise, they immediately have half an understanding of the story. They have an idea what the relationship is, what’s going on. And that can work for you two ways. If it’s very well known, you can take it and completely subvert it; you can change the meaning completely and surprise people with something unexpected. If it’s a little less well known, it can just be a way in, a helpful sort of tool, so you don’t have to spend your whole time explaining what the story is.

Cathy Fitzgerald: And are there any other paintings in the National Gallery that you’ve used over the years? Who else have you lampooned?

Dave Brown: Another recent cartoon was based on Henri Rousseau’s tiger and it was at the time of the protests over China and their attitude to Tibet and of course the Olympics. So its title is the same as Rousseau’s, it’s ‘Surprised! Tiger Caught in a Storm’. The tiger in my version is the Chinese premier and he’s surprised by the storm of outrage over Tibet. And in front of him are five skulls, arranged to look like the rings of the Olympic logo, and the tiger’s claws and fangs are rather bloodied.

Cathy Fitzgerald: And who have you got in your sights next? Boris Johnson?

Dave Brown: Yes, I imagine I’ll be drawing Boris sometime fairly soon, I’m not quite sure what as. I must scour the National Gallery for blond-headed toffs, I think, and see who I might possibly draw him as.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Cathy Fitzgerald talking to Dave Brown, whose ‘Rogue’s Gallery’ series has recently been published as a book. If you’d like to see Holbein’s original version of ‘The Ambassadors’ for yourself, without George Bush, pop along to the Gallery where it’s currently on display.

That’s it for this episode, but we’ll be back in July with more news from the National Gallery, London. Until then – goodbye!