Author: Amanda Lillie

3. The ruined temple: architecture subject to time

Sandro Botticelli’s ‘Adoration of the Kings’ [link to entry] tondo (fig. 11) belongs to a different tradition from that of Ercole. The rustic element of the construction, in keeping with the presence of the shepherds, has receded into the makeshift stable roof seen in the background, to be replaced by the ruins of a great church or basilica suitable for the visit of the Three Kings.17 Again, architecture plays a dominant role in creating the mood and meaning of the work. The whole concept of vast ruined arches, and particularly the three horizontally positioned arches to the left, may evoke the remnant of the ancient basilica at the edge of the Roman Forum known in the 15th century as the Temple of Peace (‘Templum Pacis’, fig. 12).18

Herbert Horne’s eloquent description of this painting in his 1908 monograph draws our attention to the architecture which he describes as:

'a strange, indescribable piece of antiquity, as of some vast, cruciform church, the roofless arches of which rise into the clear air and measure out the space of the heavens. The building, temple or basilica, or whatever it may be, is raised above a vaulted under-croft; and below, in the foreground of the painting, among its shattered piers, Botticelli has grouped the figures of his story, to the number of seventy or more, which have ascended from either side into the nave or body of the ruin. It is in the design of this architecture, and in the art with which the figures are disposed before it, and proportioned to it, that, what is now the chief beauty of the picture, its imposing effect of courtly spaciousness, largely consists… In originality and subtlety of design, Botticelli certainly never afterwards surpassed himself in this kind of composition.'18

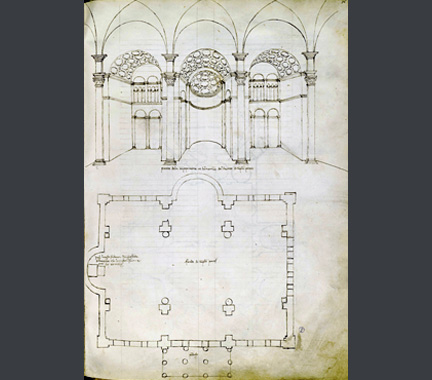

Botticelli’s architecture in the ‘Adoration’ tondo raises many questions, retaining the mystery of the ruin. The first difficulty is to imagine what type of building this might be and its ground plan. We seem to be looking into a longitudinal nave, its portal strongly suggested by huge blocks of stone guarding the entrance to the image, its roof once supported by a series of arches resting on a giant order of rectangular piers. Extending at right angles to this nave, to the left, a further series of arches of the same classical order and height continue beyond the picture’s edge. A giant transept might be implied, especially when a close inspection reveals that Botticelli originally extended this arcade across the right-hand side of the picture (fig. 13);20 but it is not clear how this ‘transept’ connects with the ‘nave’.

Perhaps the infill with walls of roughly hewn stone (in front and around the ox and the ass) marks the point of intersection between ‘transept’ and ‘nave’ (fig. 20).21 In plan this is surely a basilica in the Christian sense – a church rather than an Ancient Roman meeting hall. Its plan must have been selected for its cross shape inscribed in the circle of the panel, placing Christ at the very centre.

Apart from its ground plan, the cross-section of this building with three different floor levels is unusual in painted architecture. At the lowest level to the left and right the arches of an undercroft are visible; the nave is at ground level; and resting on the undercroft to left and right is the raised transept (fig. 14).

Botticelli may have been imagining a medieval basilica like San Miniato in Florence (about 1018–1207), where the crypt, nave and raised choir are all simultaneously visible inside the main entrance (fig. 15).

Was this an evocation of a venerable Florentine church, perceived as ‘ancient’, and the largest surviving local basilica of this type?22 This must remain doubtful, for in other respects Botticelli’s basilica would have looked resolutely modern in 1475.23 Instead of round columns it has rectangular piers with framed flat panels set into each face. There was a vogue for this type of pier among Florentine architects from about 1465 to about 1485, and this building recalls the rather severe rectilinear style developed by Giuliano da Maiano for the cathedral of Faenza (begun 1474, fig. 16) and the basilica of the Santa Casa at Loreto (1461–86), and by Francesco di Giorgio for Urbino Cathedral (planned from 1460, built from about 1477, now destroyed), all of which employed piers.24

Its huge projecting transept may relate to plans for St Peter’s in Rome begun under Pope Nicholas V (1447–55) and continued under Paul II (1464–71).25 Botticelli’s choice of capital at first appears idiosyncratic and certainly did not derive from Ancient Roman capitals he could see reused in Florentine churches such as San Miniato and Santi Apostoli, nor from contemporary examples.

On closer inspection, however, it is clear that he conceived of pier capitals as quite different from column capitals, and designed them like short strips of cornice, consisting of five stacked elements: a water leaf motif, palmettes, egg and dart, bead and reel, and stopped fluting (fig. 17). This vocabulary could have been taken from Roman Ionic cornices, perhaps from a specific example he had seen.26 But his fundamental approach was similar to that adopted by Alberti for the piers supporting arches at the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini;27 and the solution appears again at Urbino Cathedral, where the pier capitals were parts of the entablature wrapped around the interior.28

There may have been a number of reasons for the modernity of the temple in Botticelli’s tondo.29 One may be that it was the ruined condition of the building that mattered, not its form, so that a modern ruin was just as acceptable. A second possibility is that an ‘all’antica’ building, that is a modern structure designed in the ancient manner, could satisfactorily perform the role of an ancient building.30 A third, theological, reason might be that by projecting forwards into modern time the building draws a parallel between the end of the old order and the end of the new order, demonstrating the enduring power of the Incarnation. Or, as Aby Warburg expressed it: ‘In fifteenth-century art, “the antique” does not necessarily require artists to abandon expressive forms derived from their own observation’. Here we can observe Botticelli’s dual response, his ‘resistance and submission’ to antiquity.31

Designing a ruin

Whereas other designers of ruins tended to paint a pair of columns, or a single crumbling arch, or a piece of ancient wall, Botticelli invented an entire building. The crucial difference is that most other artists seem to have conceived of their ruins as fragments from the start, as leftover bits whose original or reconstructed shape they never fully imagined, whereas Botticelli seems to have begun with the concept of a whole building, which he then proceeded to dismantle. This reveals much about Botticelli’s thinking and his approach to architecture in painting. He was thinking like an architect, interested in understanding what a building might have looked like as a complete design and how it was put together. This is evident in his preparation for the composition, as incised lines link the different parts of the whole raised transept-like structure that originally stretched horizontally across the whole picture, with arches behind and the stumps of piers in front. Furthermore, Botticelli was not afraid to let the building dominate the composition and determine the grouping and flow of figures.

Botticelli’s approach to time is revealed in his treatment of the ruin. He was aware of the building as a changing, quasi-organic entity that responded to and marked time. He drew fine cracks in the stone and depicted weeds springing out of the ruin as though it were reverting to nature (fig. 18).

At the same time he conveys a note of foreboding by painting dropped keystones that threaten to trigger the collapse of the whole structure, as well as other precariously placed blocks of stone (fig. 19).

He takes the anachronistic juxtaposition of the Nativity and the ruined temple a step further by not only having Christ born inside the ruined temple, but showing precisely how it was converted to use as a stable, the open arches of its crossing infilled with big blocks of rougher stone to support the wooden roof (fig. 20).

He draws attention to the incongruity and clumsiness of these improvised and partly collapsed rough walls – and the absurdly flimsy high roof which offers so little shelter – in comparison to the grand scale, elegant proportions, and smooth white stone of the temple.32

Botticelli took a symmetrical architectural composition and rendered it asymmetrical when he decided to paint over the arches of the right-hand transept.33 He took a more complete and comprehensible ruin and ruined it further until its overall structure was hard to make out. By removing the connecting links in the building, the artist seems to want to withhold something, like an architectural puzzle from which key pieces have been removed so we will never be able to see it complete.34 But it is the missing parts that make ruins evocative and compelling in the way that unfinished stories hold our attention and make us want to know or invent an ending. In creating this insoluble ruin Botticelli makes us realise that the past is unknowable.

At the same time, by eradicating the building on the right, Botticelli gives greater prominence to the peacock, a symbol of resurrection and regeneration. Thus the left part of the image, the ruined building, would refer to decay and the old order, while the right side would refer to immortality as symbolised by the bird. Instead of fixing a time or period for the Nativity, Botticelli deals with two simultaneous notions of time: the ruined temple, which is subject to time and change, and Christ who is not. The cracks, falling keystones and missing parts, all demonstrate how the Roman building is a victim of time in a way that Christ never will be. The dissonance between these two types of time asserts the trans- or super-historicity of the birth.

Read further sections in this essay

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The stable of the nativity: holy rusticity and primitive time

- 4. Mysterious ruins: the nostalgia of receding time

To cite this essay we suggest using

Amanda Lillie, 'Architectural Time' published online 2014, in 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting', The National Gallery, London, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/architectural-time/the-ruined-temple