Andrea Previtali, about 1480–1528

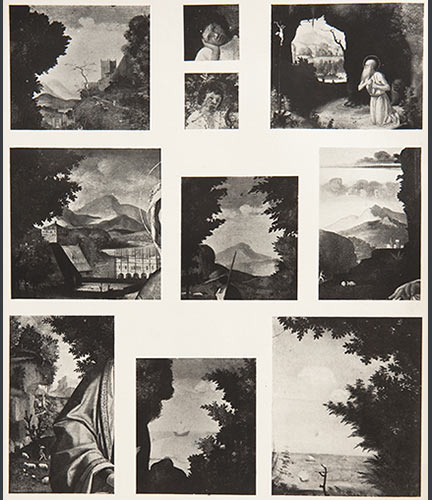

'Scenes from Tebaldeo's Eclogues: Damon broods on his Unrequited Love / Damon takes his Life', about 1510

Oil on wood, 45.2 x 19.9 cm

NG4884.1

Andrea Previtali, about 1480–1528

'Scenes from Tebaldeo's Eclogues: Thyrsis asks Damon the Cause of his Sorrow / Thyrsis finds the Body of Damon', about 1510

Oil on wood, 45.2 x 19.9 cm

NG4884.2

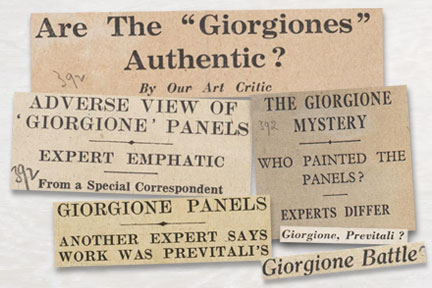

These two panels were acquired by the National Gallery in 1937 as works by Giorgione. A considerable amount of money was spent on them, attracting attention from the media and public alike. When art historians started to assert that the paintings were indeed not by Giorgione but by a follower, the growing scandal – dubbed by the newspapers ‘The Giorgione Controversy’ – exploded.

Acquisition

The two panels were seen by Kenneth Clark in Vienna in 1937, while in the possession of the Austrian dealer Oskar Salzer. Only a year before, they had been in the Da Porto collection, near Vicenza. The National Gallery acquired them for the then considerable sum of £14,000. The resulting press release, entitled ‘Four Newly Discovered Giorgiones for the National Gallery’, makes clear the importance placed on their acquisition, raising public expectation and interest.

'The Giorgione Controversy’

However, prominent art historians such as Tancred Borenius (‘my old friend’, as Clark would ironically call him) started immediately to question the attribution of the two panels to Giorgione. Borenius attributed them – rather unconvincingly – to Palma Vecchio. Nevertheless, Pandora’s Box had been opened. Shortly afterwards, in 1938, G.M. Richter published the panels as works by Andrea Previtali.

Notes on photographs of works by Previtali in the Gallery archive make it clear that this attribution was, in fact, the work of Philip Pouncey, at the time a young member of the curatorial staff. In defiance of his Director’s view, Pouncey informed Richter of his thoughts and provided him with the comparisons illustrated in Richter’s article.

Since then, the attribution of the panels to Previtali has been little questioned, and Clark himself soon revised his opinion.

At the same time, the press started a strong campaign against what was thought to be an irresponsible use of public money, and Clark’s detractors and enemies seized the opportunity to attack the National Gallery. The scandal grew, and questions were even asked in Parliament about the sum paid to Oskar Salzer, who had apparently bought the paintings the previous year for less than £40.

Why Giorgione?

At the time of the acquisition, Kenneth Clark was the young director of the National Gallery, where the perceived lack of a proper painting by Giorgione was strongly felt. Giorgione’s works have always been highly desired by collectors and museums, but there are less than a dozen pictures that are surely attributable to him. This may have been the main reason why Clark convinced himself that the paintings he saw were by Giorgione.

The incredible misunderstanding that the pictures generated was also due to the fact that they are indeed early 16th-century works, probably painted in Venice, and certainly showing a strong influence of the art of Giorgione. Andrea Previtali, a native of Bergamo, spent his youth in Venice and was trained in the workshop of Giovanni Bellini. Previtali was clearly not indifferent to Giorgione’s totally new concept of landscape painting, in which nature alone, in all its forms, became the subject of the representation, rather than merely a backdrop for a religious or mythological scene. Giorgione’s innovative approach is beautifully demonstrated in his famous works ‘La Tempesta (The Tempest)’ (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice) and Il Tramonto (The Sunset).

Subject

The subject of these four small panels was soon recognised by Ernst Gombrich as inspired by the second eclogue (pastoral poem) of the Ferrarese poet Antonio Tebaldeo. Editions of this poem were published in Venice around 1500.

The tragic story must be looked at in reading order. The first scene is the one at the top of the left panel, which portrays the melancholic and solitary Damon, suffering for his unrequited love for Amaryllis. In the second scene (top of the right panel) his friend Thyrsis tries to console him.

In the third scene (bottom of the left panel) Damon kills himself with a dagger in his breast. The last scene shows him found by Thyrsis in a pool of blood.

Antonio Mazzotta is the Pidem Curatorial Assistant at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

K. Clark, ‘Four Giorgionesque Panels’, ‘The Burlington Magazine’, vol. LXXI (1937), pp. 199–207

N. Penny, ‘National Gallery Catalogues. The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings. Volume I. Paintings from Bergamo, Brescia and Cremona’, London 2004, pp. 291–9

G.M. Richter, T. Borenius and T. Bodkin, ‘Four Giorgionesque Panels’, ‘The Burlington Magazine’, vol. LXXII (1938), pp. 33–7