Italian

‘Portrait Group’, early 20th century

Oil and tempera on wood, 40.6 x 36.5 cm

NG3831

Sometimes we see what we want to see. When this Italian ‘Renaissance’ portrait was acquired by the National Gallery in 1923, it was hailed as a unique painting by an undiscovered master of the 15th century. Since the 1950s, connoisseurship, art historical research and scientific analysis have combined forces to unmask a remarkably sophisticated 20th-century forgery.

This portrait was acquired by the National Gallery in 1923 as a painting of the late 15th century, possibly by an accomplished but unknown artist in the circle of Melozzo da Forli (1438−1494), an artist primarily active in Urbino and Rome. The armorial badge stamped into the gesso at upper right suggested the sitters were members of the Montefeltro family of Urbino, although no family members of the appropriate age and gender could be identified.

Doubts and deliberations

Even at the time of acquisition, some of the picture’s physical properties baffled researchers. The peculiarly impervious nature of the paint, in particular, attracted attention: as former Gallery Director Sir Charles Holmes commented, it was "painted in tempera of an almost flinty substance, covered with a curiously hard brown varnish."

In April 1924 the painting was examined by the restorer A.H. Buttery, largely to quell doubts about its authenticity. Buttery felt strongly that it was an authentic 15th-century painting, and "proceeded to test this view by heat and by applying pure solvent to various portions of the picture". As his methods barely managed to disturb the varnish, Buttery declared the painting unquestionably of the 15th century and congratulated the Trustees on their astute purchase. The National Gallery subsequently issued a statement announcing that the painting’s antiquity "was again conclusively demonstrated".

In the Gallery’s catalogue of early Italian paintings published in 1951, however, opinion had shifted, with curator Martin Davies concluding that ‘this picture appears to be modern’. Further evidence of the modern origins of Portrait Group emerged in 1960, when costume historian Stella Mary Newton demonstrated that the garments worn by the figures were both anachronistic and structurally impossible. In fact, the man’s chequered cap was inspired by a distinctive women’s fashion of about 1913.

Scientific analysis

The painting’s curious technical aspects remained largely unexplored until 1996, when a scientific investigation was launched to determine how the forgery was crafted. ‘Portrait Group’ was painted on a thin wood panel, which was stuck on to a thicker panel of old wood and artificially cracked to heighten the impression of great age.

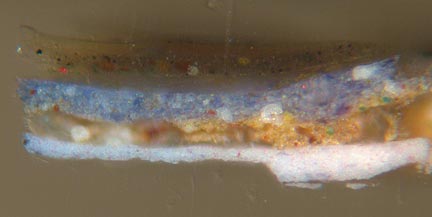

Although the traditional gesso ground and egg tempera medium were used (the latter confirmed by GC-MS analysis and FTIR microscopy), SEM-EDX analysis identified a number of modern pigments in the samples: cobalt blue, cadmium yellow, viridian and chrome yellow. None of these were available before the 19th century.

The paint layer is covered with a layer of shellac (a resin-like substance secreted by the lac insect) mixed with pine resin − probably a cheap, commercially prepared varnish. Covering this is a layer of what appears to be animal glue, deliberately tinted to give the appearance of age, and a second layer of varnish. These upper layers produced the curiously ‘flinty’ character and brownish tonality of the deceptively aged surface. As the shellac dried it contracted, creating a craquelure in the paint below. Superficially at least, this simulated the surface craquelure typical for paintings of the 15th century.

Modern forgers

Although scientific investigation has revealed the methods used to manufacture the painting, we still do not know who might have devised such a complex and sophisticated forgery. It has been proposed that the Gallery’s picture is the work of the Italian restorer and master forger Icilio Federico Joni (1866–1946). However, it bears little resemblance to his usual forgeries of 14th- and early 15th-century Sienese paintings. Recently it has been suggested that one of Joni’s contemporaries, Umberto Giunti (1886–1970), might have painted the work.

Different visions

It may seem surprising that the ‘Portrait Group’ could ever have been mistaken for an authentic Italian portrait of the late 15th century, even without the insight of modern scientific analysis. The hard linearity of the figures grossly exaggerates the delicate clarity of 15th-century profile portraits, and the faces themselves seem just a little too modern.

However, early 20th-century viewers could easily have discounted features made familiar by the taste of their own age. Details that now appear inappropriately modern would have simply proved for those viewers the ‘ageless’ appeal of Renaissance painting.

Marjorie E. Wieseman is Curator of Dutch paintings at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

M.E. Wieseman, ‘A Closer Look: Deceptions and Discoveries’, London 2010, pp. 36–8

M. Wilson, ‘If the Paintings Could Talk’, London 2008, p. 57