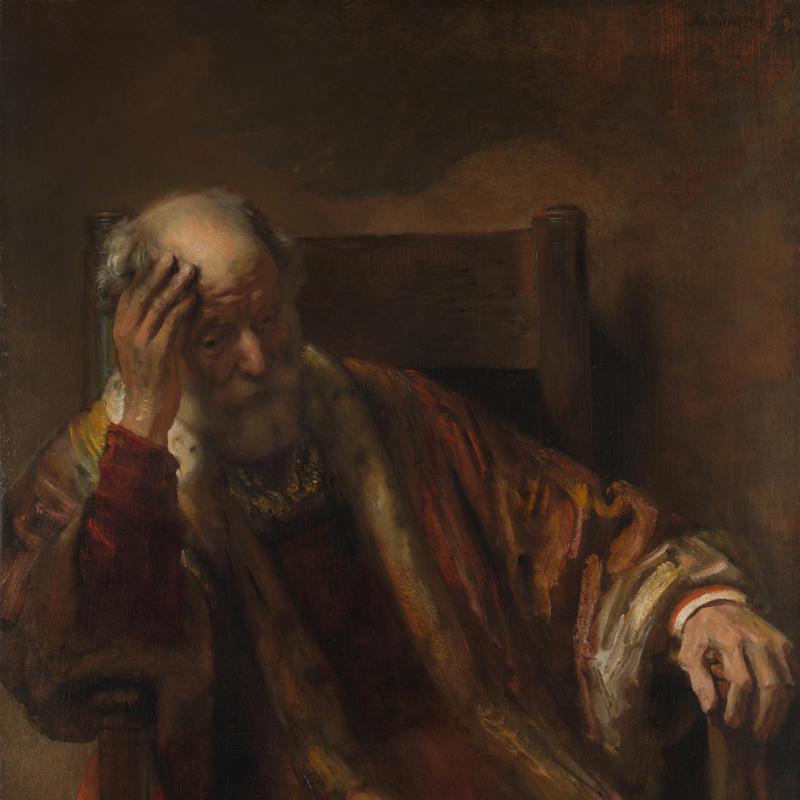

Follower of Rembrandt, 1606–1669

'An Old Man in an Armchair', 1650s

Oil on canvas, 111 x 88 cm

NG6274

Some of Rembrandt’s most powerful paintings combine his characteristically bold brushwork with a lifelong interest in depicting men and women immersed in thought. These evocative works were imitated and emulated by his many pupils and followers. Over time many of these paintings, including An Old Man in an Armchair, were mistaken for works by Rembrandt himself. A combination of connoisseurship and scientific analysis, and a knowledge of historic painting practice, can help to refine our understanding of these pictures.

A ‘Venetian’ Rembrandt

When the National Gallery acquired this painting in 1957, it was praised as a powerful example of Rembrandt’s work of the 1650s. Sir Kenneth Clark remarked on the pronounced ‘Venetian’ aspect of the painting, citing the pure, saturated colours and the use of glazes to create depth of tone. Clark felt the painting showed the influence of Tintoretto, although it is not at all certain that Rembrandt would have known the work of the Venetian master. By the late 1960s a more systematic comparison of ‘An Old Man in an Armchair’ with authentic works by Rembrandt, and a greater understanding of the materials and techniques of paintings by Rembrandt and artists in his circle, enabled scholars to recognise the Gallery picture as the work of a contemporary follower.

Looking at technique

‘An Old Man in an Armchair’ is superficially convincing as a work by Rembrandt. The subject of an old man in contemplation is a common theme in Rembrandt’s oeuvre. The painting bears a signature and date at upper right. Yet there are aspects of quality, technique and handling of paint that find no parallel in the master’s work.

There is a disparity in style between the handling of the beard, fur coat and right hand of the sitter and his left hand and sleeve, which are rendered in an almost impressionistic manner.

The noted ‘Venetian’ effect results largely from the use of comparatively pure pigments: the bright red on the man’s left cuff is pure vermilion, the orange-yellow streaks in his robe are just natural earth pigment, and the deep purplish glazes consist solely of red lake pigments. This use of red lake glazes on the sitter’s gown and on his hand would be most unusual in authentic paintings by Rembrandt of this period.

© Six Collection / Bridgeman Art Library, London

Materials and their use

The painting cannot simply be dismissed as a later imitation, however. The materials used suggest that it was produced either in Rembrandt’s studio during the 1650s or by a contemporary painter emulating Rembrandt’s style. The canvas was prepared with a double ground typical of Dutch 17th-century practice. Examined microscopically and by EDX, the ground was found to consist of a lower layer of orange-red earth pigment and a dull brownish-olive upper layer, containing lead white, wood charcoal and some yellow ochre.

Similar grounds have been identified in Rembrandt’s portraits of Jacob Trip and Margaretha de Geer of about 1661, which would indicate that ‘An Old Man in an Armchair’ may also have originated in Rembrandt’s studio. Many of the specific pigments found in the ground layers of these pictures have also been identified in the paint itself. This would suggest – unusually – that the grounds may have been applied in the studio rather than the canvases having been commercially primed.

Education and emulation

But who might have painted this ‘Rembrandtesque’ work? We know that Rembrandt encouraged his pupils not just to copy his work as a way of learning from it, but also to create independent paintings inspired by motifs or themes borrowed from those works. Before they became masters in their own right, guild regulations prohibited pupils from signing their works, and some of their better efforts may have been provided with the master’s signature before leaving the studio.

A convincing author has yet to be found for this evocative painting of an old man immersed in thought. Careful connoisseurship and continued scientific investigation of works by Rembrandt and his followers may eventually solve the puzzle.

Marjorie E. Wieseman is Curator of Dutch paintings at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

D. Bomford, J. Kirby, A. Roy, A. Rüger and R. White, ‘Art in the Making: Rembrandt’, London 2006, pp. 210–13

N. Maclaren, ‘National Gallery Catalogues. The Dutch School 1600–1900’, rev. edn by C. Brown, 2 vols, London 1991, vol. 1, pp. 376–7

M.E. Wieseman, ‘A Closer Look: Deceptions and Discoveries’, London 2010, pp. 58–9