Ovid and the Narcissus myth

In the Roman poet Ovid’s version of the Narcissus myth, Narcissus’s mother is told in a prophecy that Narcissus will reach old age, so long as he never recognises himself. He grows up to be a beautiful young man, admired by men and women alike.

One day, during a hunt, Narcissus grows thirsty and finds a stream to quench his thirst. As he leans down, however, he becomes utterly bewitched by his own reflection. His most notable admirer, the nymph Echo, is often depicted in art looking wistfully at Narcissus, who looks ever more wistfully at his own reflection. Unable to tear himself away from the sight of himself, Narcissus eventually withers and dies, and a narcissus, or daffodil, is found in place of his body.

The Narcissus myth is most often interpreted as a cautionary tale against the perils of self-obsession – the pool of water serving as a metaphor for the mirror, and with it, the dangers of vanity and excessive self-involvement. This interpretation has since been reinforced by the term ‘narcissism’, which, coined in the late 19th century and popularised by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, derives its name from the Narcissus myth.

Narcissus and male beauty

Even if the Narcissus myth was designed to be a cautionary tale, this hasn’t stopped artists through the ages from appreciating Narcissus’s beauty. This was especially apparent in the Renaissance period, which saw artists borrowing from Classical conceptualisations of male beauty.

Boltraffio’s (follower of) Narcissus (above), for instance, depicts him with flowing ringlets of hair and smooth, gently flushed cheeks – an idealised man. In the Renaissance period, some depictions of Narcissus appear to be more an appreciation of male beauty than an attempt to convey a moral message about Narcissus’s self-absorption.

The Baroque artist Caravaggio depicts Narcissus with parted lips, peering over a pool, totally absorbed by his own reflection. As viewers, it is hard not to be drawn to Narcissus’s beauty in the same way that Narcissus is himself captivated by it.

Meanwhile, Echo – the wounded party who is left by the wayside due to Narcissus’s self-obsession – is often absent from some of the more eroticised depictions of the myth.

Narcissus and queer desire

Narcissus’s desire for himself has traditionally been framed as a misplaced, if not, ‘wrong’, kind of desire. In other words, by desiring himself, Narcissus does not desire who he is ‘meant’ to; he possesses a desire that cannot be fulfilled.

The non-normative nature of Narcissus’s desire has spoken to the experiences of LGBTQ+ people living in cultures in which they are not accepted. There are affinities between queer desire, which can feel 'impossible', and Narcissus’s own impossible desire.

An often overlooked reading of Ovid’s version of the Narcissus myth is that Narcissus’s desire is inherently queer. In the myth, Narcissus initially thinks he is desiring another man – he does not immediately realise that the reflection in the water is himself.

Narcissus in the Victorian era

The Narcissus myth was adopted in literary and artistic circles in Britain and France in the late 1800s. Its themes of forbidden or non-normative desire resonated with the late 19th-century decadent and Aesthetic Movements, which often revelled in the beautiful, the excessive, the forbidden, and the queer.

Leighton House, the West London house-studio of Lord Frederic Leighton, is a sumptuous example of how the Narcissus myth was adopted by the Aesthetic Movement. The house’s Narcissus Hall features turquoise ceramic tiles by William De Morgan and a bronze statue of Narcissus in the centre of the room.

French Symbolist artist Gustave Moreau’s Narcissus demonstrates how the myth found a natural home in decadent culture, with its themes of decline and decay. Surrounded by ornate, blousy flora and fauna, a lithe Narcissus uses a stick to prop himself up. The painting is heavy with foreboding, as Narcissus’s head hangs heavy, and his sleepy eyes gaze down into the pool.

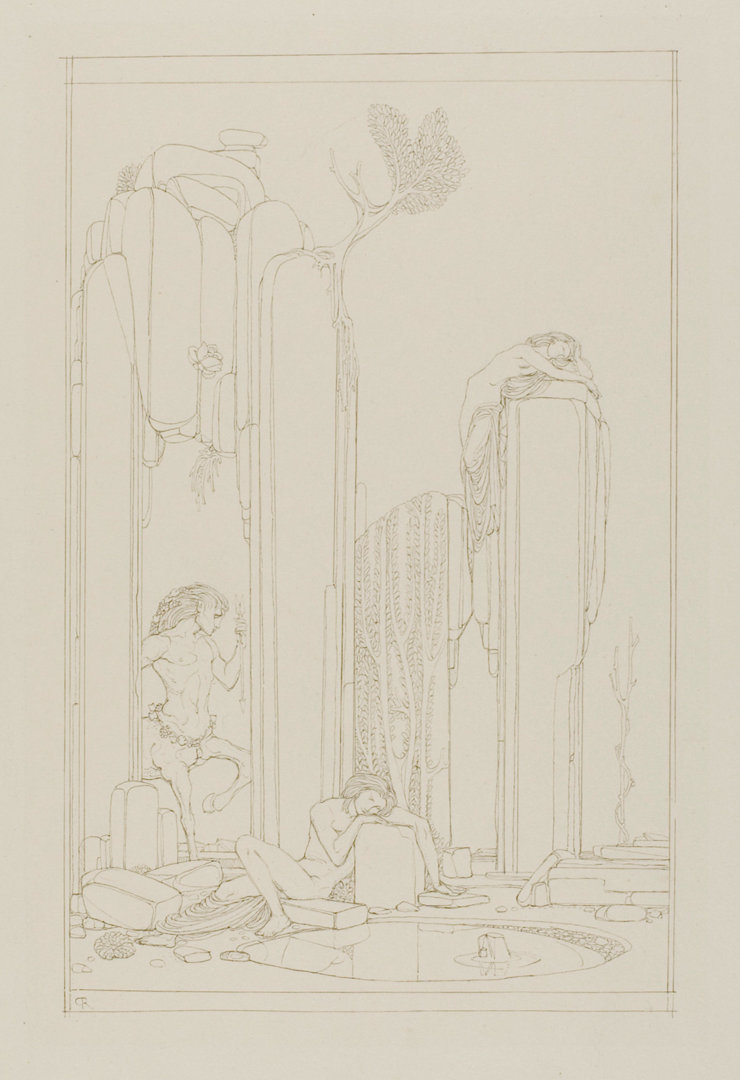

In decadent culture, androgyny, with its sexual ambiguity, was sometimes employed as a coded way of expressing queer desire. British artist Charles Ricketts’ illustration of Narcissus features an androgynous figure who gazes mournfully at his own reflection, surrounded by ruins.

Ricketts drew Narcissus to accompany a humorous prose poem Oscar Wilde wrote about Narcissus, named ‘The Disciple’. In this playful reimagining, the pool claims it loves Narcissus because in Narcissus’s eyes, the pool saw its own beauty mirrored, revealing the pool and Narcissus to be one and the same – both using each other only to see themselves, both as bad as each other.

Elsewhere in literature, Narcissus is refashioned into an aesthete (a representative of the Aesthetic Movement). Wilde makes frequent reference to the Narcissus myth in his novel, 'The Picture of Dorian Gray' (1890), where the protagonist, Dorian Gray, obsessed with his own beauty, is likened to Narcissus.

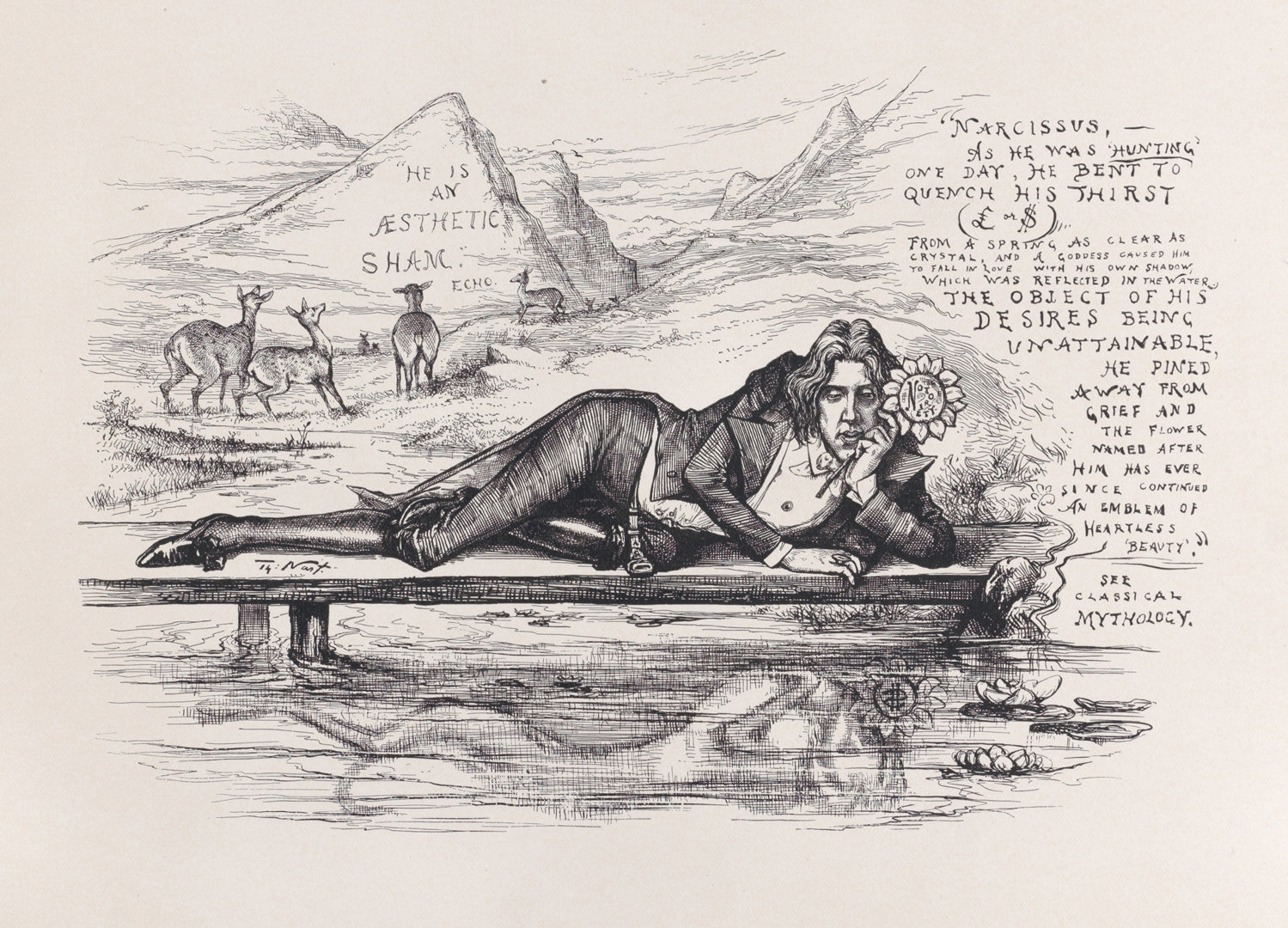

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Wilde himself was lampooned using the Narcissus myth. In a caricature by Thomas Nast, produced at the time of Wilde’s American lecture tour in 1822, Wilde can be seen lounging before a pool of water, clutching a sunflower bearing the word ‘Notoriety’. In the pool, which seemingly reflects the truth, the sunflower bears a dollar sign, implying Wilde coveted notoriety for the sake of fame and money.

Narcissus in contemporary queer art and culture

In modern times, Narcissus has been depicted in explicitly and unashamedly homoerotic ways. In 2012, the French photographer duo, Pierre et Gilles, recreated a bare bottomed Narcissus, idly admiring his own naked reflection.

James Bidgood’s art house film 'Pink Narcissus' (1971) also offered a kitschy, camp take on the Narcissus myth, bringing the myth out of its Classical setting and into the urban metropolis of the modern world. In the film, Narcissus is reimagined as a young gay man who roams the city, in search of spiritual and sexual fulfilment.

Like all myths, the Narcissus myth has produced countless reinterpretations. Throughout history, queer individuals have seen the myth as theirs for the taking, often knowingly fashioning it to fit their own desires and remaking Narcissus in their own image.

Digital activity at the National Gallery is supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies Digital Accelerator