Carlo Crivelli, 'Saint Thomas Aquinas', 1476

About the work

Overview

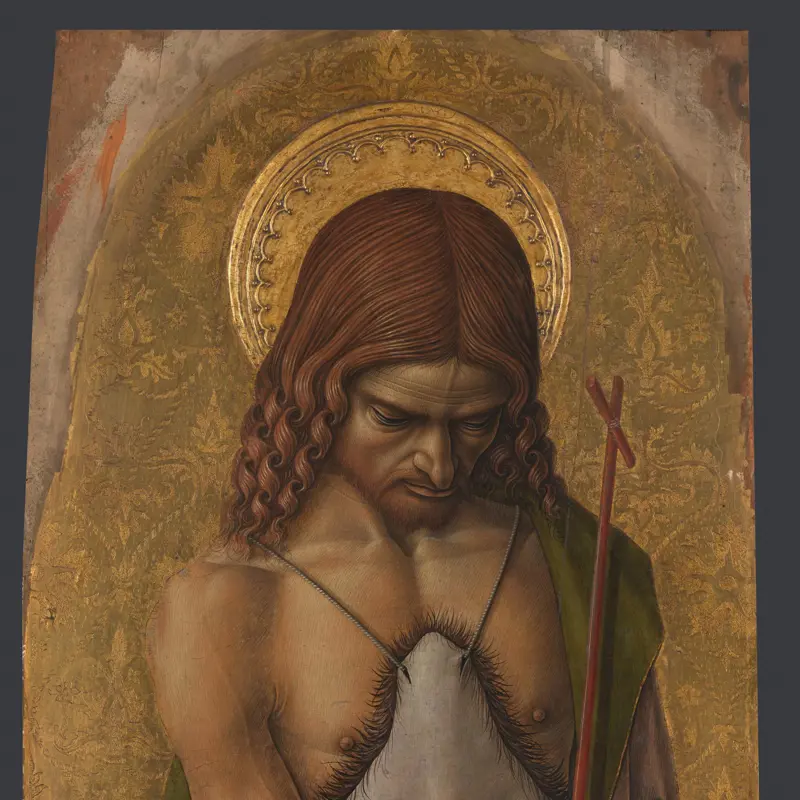

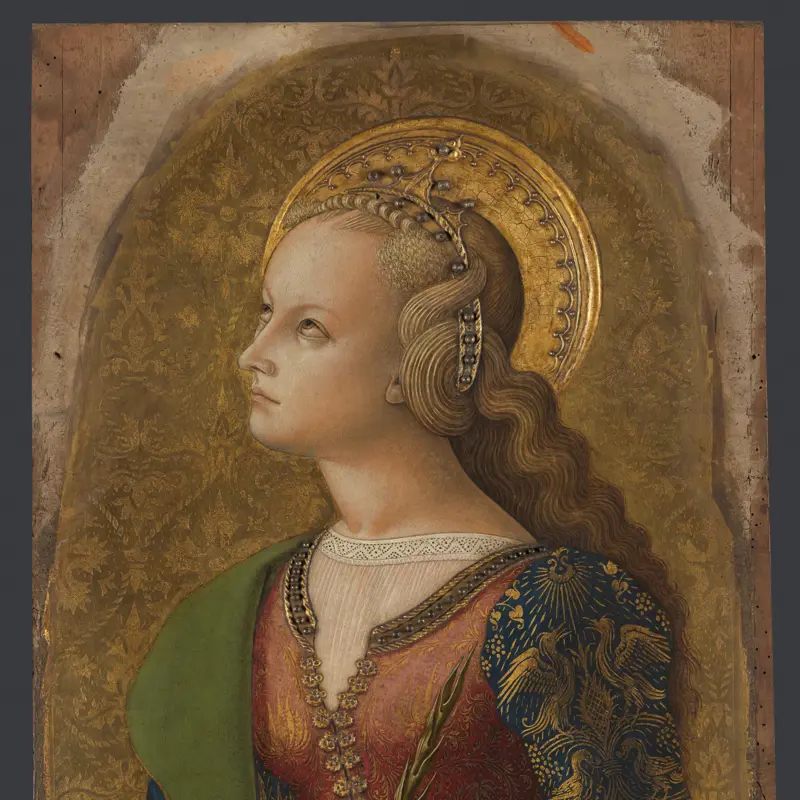

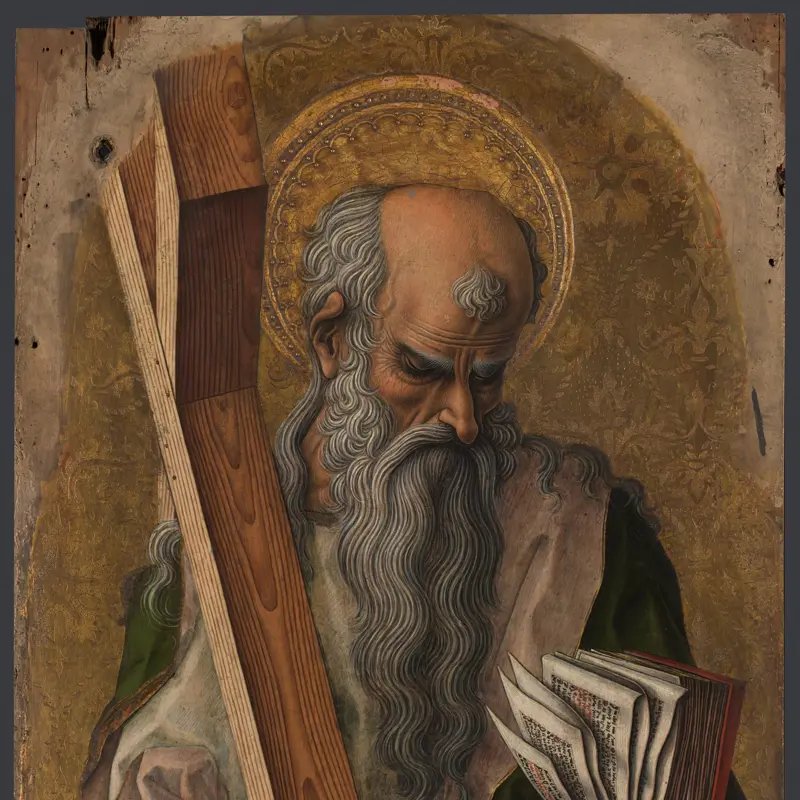

This half-length figure of a saint comes from the upper tier of a polyptych (multi-panelled altarpiece) which Crivelli painted in 1476 for the high altar of the church of San Domenico, in Ascoli Piceno in the Italian Marche. He is the theologian and Dominican friar Saint Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274). His strong features and the vigorous set of his jaw express his intellectual authority, as does the book he clasps in his left hand, his fingers holding open its fluttering pages.

Crivelli has painted the book half open, with fore-edge towards so us that we see the crinkled edges of the parchment pages; he has made it look like a three-dimensional object, although we know it is not. Crivelli’s skill as a painter of drapery is such that even though Thomas’s robes are black, we can see the deep folds of the hood around his shoulders. The severity of his black and white robes – the uniform of the Dominican Order – contrasts with the opulent gilding of the background.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- Saint Thomas Aquinas

- Artist

- Carlo Crivelli

- Artist dates

- About 1430/5 - about 1494

- Part of the group

- The Demidoff Altarpiece

- Date made

- 1476

- Medium and support

- Egg tempera on wood (poplar, identified)

- Dimensions

- 60.5 × 39.5 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1868

- Inventory number

- NG788.9

- Location

- Room 10

- Collection

- Main Collection

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Martin Davies, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools’, London 1986 and supplemented by Amanda Hilliam, Jonathan Watkins et al., ‘Carlo Crivelli: Shadows on the Sky’, Birmingham 2022; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Bibliography

-

1724D.T. Lazzari, Ascoli in prospettiva: Colle sue più singolari pitture, sculture e architetture, Ascoli 1724

-

1766F.A. Marcucci, Saggio delle cose ascolane e de'vescovi di Ascoli nel Piceno dalla fondazione della città sino… all'anno mille settecento sessanta sei, Teramo 1766

-

1790B. Orsini, Descrizione delle pitture, sculture, architetture ed altre cose rare della insigne città di Ascoli nella Marca, Perugia 1790

-

1822L.A. Lanzi, Storia pittorica della italia dal risorgimento delle belle arti fin presso al fine del XVIII secolo, Florence 1822

-

1834A. Ricci, Memorie storiche delle arti e degli artisti della Marca di Ancona, Macerata 1834

-

1852Quelques tableaux de la galerie Rinuccini décrits et illustrés, Florence 1852

-

1900G.M. Rushforth, Carlo Crivelli, London 1900

-

1901A. Venturi, Storia dell'arte italiana, 11 vols, Milan 1901

-

1905S. Reinach, Répertoire de peintres du Moyen Âge et de la Renaissance (1250-1580), 4 vols, Paris 1905

-

1907L. Venturi, Le origini della pittura veneziana 1300-1500, Venice 1907

-

1927F. Drey, Carlo Crivelli und seine Schule, Munich 1927

-

1932B. Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works, with an Index of Places, Oxford 1932

-

1934L. Serra, L'arte nelle Marche, Pesaro 1934

-

1936B. Berenson, Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi, Milan 1936

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1952P. Zampetti, Carlo Crivelli nelle Marche, Urbino 1952

-

1961M. Davies, The Earlier Italian Schools, 2nd edn, London 1961

-

1961F. Zeri, 'Cinque schede per Carlo Crivelli', Arte antica e moderna, IV, 1961, pp. 158-76

-

1975A. Bovero, L'opera completa del Crivelli, Milan 1975

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

1986P. Zampetti, Carlo Crivelli, Florence 1986

-

1991J. Dunkerton et al., Giotto to Dürer: Early Renaissance Painting in the National Gallery, New Haven 1991

-

1992F. Zeri, Giorno per giorno nella pittura: Scritti sull'arte dell'Italia centrale e meridionale dal Trecento al primo Cinquecento, Turin 1992

-

1994F. Haskell et al., Anatole Demidoff, Prince of San Donato (1812-70) (exh. cat. Wallace Collection, 10 March - 25 July 1994), London 1994

-

1995P. Zampetti, Crivelli, Florence 1995

-

1998F. Gennari, 'It will form such an Ornament for Our Gallery': La National Gallery e la pittura de Carlo Crivelli (1856-1868), n.p. 1998

-

1998A.C. Tommasi (ed.), Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle: Conoscitore e conservatore: Atti del convegno, Venice 1998

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2002A. De Angelis, 'Francesco Saverio de Zelada (1717-1801)', Ricerche di storia dell'arte, LXXVII, 2002, pp. 41-53

-

2004R. Lightbown, Carlo Crivelli, New Haven 2004

-

2008R. Duits, Gold Brocade and Renaissance Painting: A Study in Material Culture, London 2008

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the group: The Demidoff Altarpiece

Overview

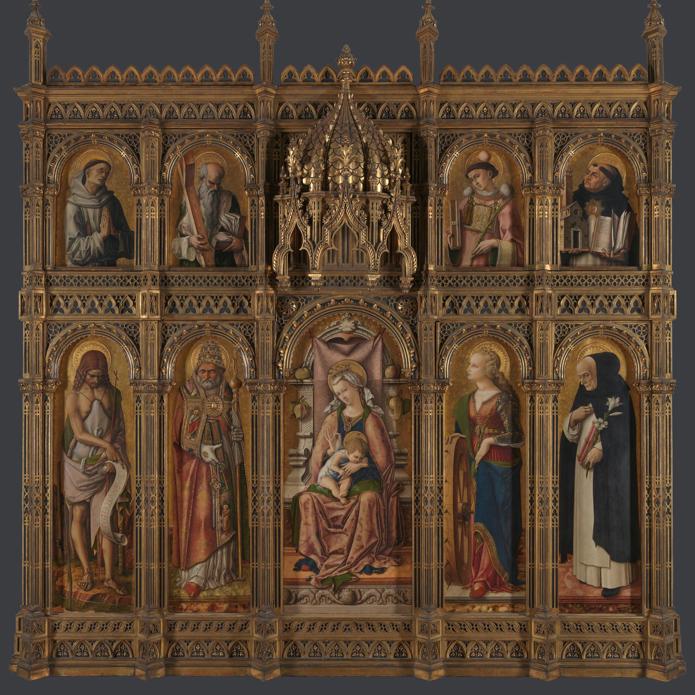

Crivelli painted two altarpieces for the small church of San Domenico, in the town of Ascoli Piceno in the Italian Marche. Their history is complex and intertwined. A large, double-tiered polyptych (a multi-panelled altarpiece) sat on the high altar, while a smaller altarpiece was in a side chapel.

In the nineteenth century parts of both altarpieces were sold to a Russian prince, Anatole Demidoff, who mounted them in a grand frame to make a three-tiered altarpiece for the chapel of his villa in Florence. The whole complex is now known as the Demidoff Altarpiece.

The National Gallery bought the Demidoff Altarpiece in 1868, and in 1961 the panels from the smaller polyptych were removed. They are now displayed separately.