Episode 7

The National Gallery Podcast

In the May 2007 podcast, find out what goes on at the National Gallery after dark. Night-time tales from security guards on patrol and author Tracy Chevalier ('Girl with a Pearl Earring'). Writer Marina Warner discusses bringing art to life.

As a bonus, listen to original poetry from two writers’ collectives, ‘The Vineyard’ and ‘Malika’s Kitchen’, inspired by the National Gallery after dark.

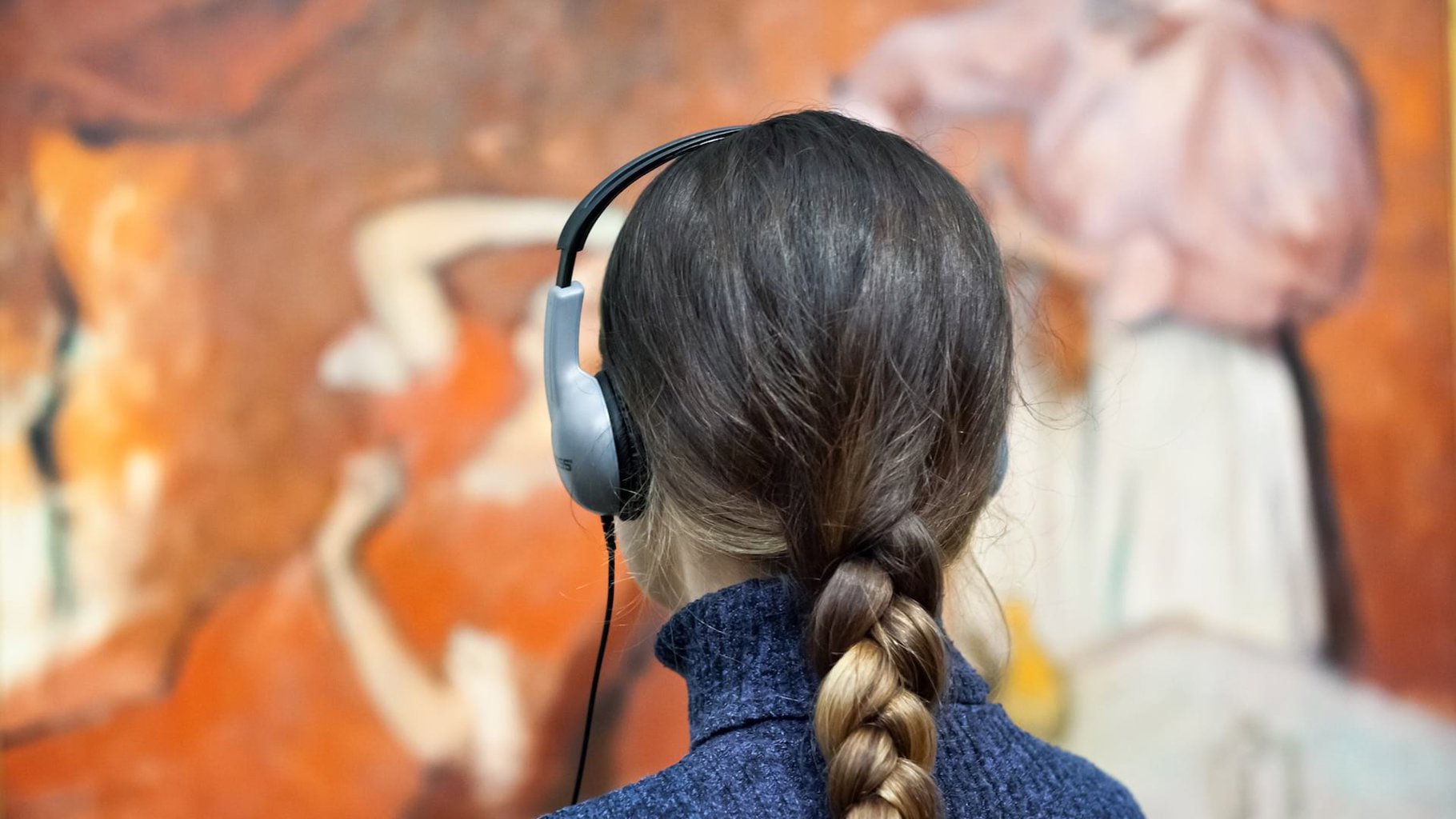

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Hello, I’m Miranda Hinkley and this is a special episode of the National Gallery Podcast. On Saturday 19 May, museums and galleries across Europe will stay open long into the evening to celebrate what’s been dubbed – the ‘Night of the Museums’. Here at the National Gallery, the ‘Renoir Landscapes’ exhibition, sponsored by Ernst and Young, will welcome visitors until 11pm. You can reserve tickets in advance at our website: www.nationalgallery.org.uk.

In preparation for the event, we’re devoting this episode to the Gallery after dark. What happens when the last visitors leave? When the lights go out and the building falls quiet? Do paintings dream? This is nocturne.

The Gallery at night: Tracy Chevalier, Marina Warner and others

Security: Closing time at the Gallery. This is a visitor announcement. The Gallery closes at 6pm…. Closing now, thank you, can we make a move please?

[Keys rattle, door shuts.]

Go ahead Michael. Can you give us a call in the control room please…

Joe Maciejczek: My name is Joe. I’ve been a security warder for 26 years.

Atmaram Kawal: My name is Atmaram Kawal. I’ve worked here for 28 years. I work as a control room security officer.

Joe Maciejczek: We start at 8 o’ clock in the evening. In summertime it’s not too bad, but in the winter it’s rather darkish. Our job is to look around the ceilings and to make sure that there are no leaks and most of the time to make sure that the building is secure.

Jacob Sam La-Rose: We are many, never silent. Even in darkness light sighs from our surfaces like sap from wounded trees. We demand your eyes and meet them with a multiplicity of our own. We are never alone.

Tracy Chevalier: My name is Tracy Chevalier. I’m the author of five novels, the best known being ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’, which is a novel about a Vermeer painting. We’re standing in a dark room with just a little light from the edge and you can more or less make out the paintings, what they are, as our eyes get better adjusted to the dark you can see. It does feel like they’re all asleep, these paintings are asleep – they’ve been here all day and everybody’s been looking at them, and they’re exhausted. They don’t want to tell their stories any more so it’s dark and they’re quiet and they’re all sleeping just the way we do. And now we’re going to wake them all up. I feel so sorry for them. But it’s almost like the paintings have to sort of regain their energy, they have to recharge, so at night they have their downtime. But boy do you feel them when you walk through, even in the dark rooms, this intense kind of feeling of presence, presence the way people have a presence.

Joe Maciejczek: Sometimes you get a very weird feeling because when you walk up close to it, and you look at it, the eyes follow you from right to left, whatever movement you move, the actual eyes – you get a feeling that the person is watching you.

Marina Warner: I’m Marina Warner and I’m a writer principally and I also teach at the University of Essex. I’ve written quite a lot about myths and legends and people’s beliefs.

One of the oldest ideas probably in mythology about art is that it comes to life. The best known story is Ovid’s ‘Pygmalion’. It’s a misogynist story – Pygmalion decides that all women are wanting, they lack the qualities that he most desires, so he creates as a sculptor, a statue, and he loves his statue so much because she’s exactly what he wants. And this is not really a very nice story. And he begins to make love to the statue and then by a marvellous piece of poetry in Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’, he feels the flesh turn warm under his fingers and she steps down from her pedestal. So this idea that statues have this really potent, uncanny life inside them belongs to quite a lot of powerful stories that have had many different versions and variations written about them.

Aoife Mannix: If you drink a painting for long enough you can breathe it into life. We slip in and out of the landscapes, they’re swirling impressions of green pathways leading deep into other worlds as we breathe our mythic conservations, a language of starry nights and crucifixions, doorways within doorways, the magic of time travel after midnight when the gardens breathe, shifting skies, the horse gallops free from the frame, and we are no longer a single expression, a moment frozen, but all the hundreds of years that have danced in the moonlight. We echo to each other…

Marina Warner: It’s got this quality of silence, that is rather different from total silence and that’s what’s eerie. Something about the people who have all gone, the visitors, leaves behind some vibration in the air, but also that the quality of all these paintings changes the actual atmosphere technically so that this is a living place, it doesn’t turn dead at all. I wouldn’t want to say that this was a kind of sacred feeling, but it’s a kind of nuance of the sacred, there’s something close to that – you feel awed and stirred. It’s got a sort of musical quality, it touches you wordlessly.

Joe Maciejczek: Well night-time is good because night-time you can actually sit down and let your mind go and let the paintings take you over. You can actually let yourself go into the paintings and sometimes you see things what you don’t normally do during the daytime, because during the daytime you’ve got the clutter of the people walking, of children whispering, and it’s a kind of a buzzing noise in the gallery all the time, but at night-time, it’s peace, and the gallery is peace and sometimes when there is peace – mind plays tricks.

Atmaram Kawal: I’m hearing all sorts of noise. Some of the places you go are scary and you feel like your hairs up, but again – it’s a job you are doing.

Joe Maciejczek: Among the areas I like to avoid is the basement area. I could hear a ball and chain following me all the time, and I was really scared because I don’t normally believe in ghosts, but it had me going for a good year, till once I was walking down there and I found out that it was the Victoria Line – it was the workers working on the lines at night-time.

Atmaram Kawal: When I go down to the area, I feel my hairs go up, that is at 2 o’ clock in the morning it’s so quiet down there, and suddenly when you hear some noise you think ‘oh my god, what is it?’. You just feel so scary you know? You want to get out of there as quickly as possible.

Tracy Chevalier: The sounds are almost like a prison. You hear these doors cranking shut and open and this clunk, clunk, clunk of the feet going down and it’s like the paintings have been stuck here and they’re in prison and that’s the funny thing about these paintings, it’s that they’re stuck here and they don’t escape – they don’t escape the frame and they don’t escape where they are, they’re always going to be here, even if you move them on a wall, they’re going to stay in the National Gallery unless they’re let out for good behaviour to some exhibition, travelling exhibition. Then they’ll go off for a little while and then they’ll come back, but it’s all the same – a wall is a wall, isn’t it?

Aoife Mannix: We echo to each other. Who’s suffered most, who’s sat for longest, who’s been restored, who got hidden during the war, who’s been painting of the month, turned into a postcard, reprinted and sold a million times, catalogued, downloaded, our faces pressed and contorted. It seemed like flattery once. But in the hushed quiet of our own eternal night, we can’t help but resent all this endless watching. We never realised that life is just a rough sketching. But now find we are layers and layers of everyone who ever looked at us.

Marina Warner: Freud’s essay on the uncanny translates the German word ‘unheimlich’ and ‘unheimlich’ actually means ‘unhomely’, literally, ‘heim’ being ‘home’, and possibly another English translation would be ‘uneasy’ in the sense that home is kind of ease-ful a place where one is comfortable, and what is uneasy is where one’s uncomfortable. But of course what Freud put his finger on was that this is somewhere in a sense that we want to be as well. It isn’t just repellent. This disturbance of the senses, this idea that there is something both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time happening has an incredibly powerful attraction and it’s an erotic attraction. I very much like the idea that what is truly, deeply disturbing is the nearly animate and it’s the absence of soul, it’s the absence of spirit, that kind of inertia that really makes one feel clammy and one wants to supply it.

And I’m interested in playing and make-believe because I think a lot of playing and make-believe that children do actually attempts to supply this missing animation. They make their dolls play, they move their figures about with play-mobile, or whatever, they try and breathe into it. And I think some of our creative urges later in life which we see expressed in quite a lot of high art is also a quality of bringing, of refusing this kind of image of death, this image of the inanimate, and bringing things to warm life. And it does stave off the fear of death at a very deep level. It doesn’t have to be conscious – this isn’t a conscious process, this is an unconscious process of attraction and fear at the same time.

Joe Maciejczek: Sometimes it reminds me that my time will come sometime and my time is close ‘cos I’m coming to retirement soon and when you come to retirement it means time to go. So sometimes when I’m in front of the altarpieces I say ‘it’s time to say your prayers Joe, because it’ll be judgement day sometime’.

Tracy Chevalier: I think the thing that’s so captivating about a museum at night is the philosophical notion of if a tree falls in a forest and no one’s there does it make a sound. I know it sounds crazy, but if there’s no one here to look at these paintings, do these paintings actually matter? Do they – they do exist, I accept that they exist, but do they matter? And I think I’ve found as a writer, that my work, my books, don’t fully exist until the reader reads them. It’s like a contract between the reader and the writer and I present something, I give something to the reader, they read it and between the two of us we make the whole work and I think paintings are the same thing – any kind of artworks are the same thing. The painter paints the painting but what does it matter unless we actually look at it? So it’s very curious to see it at night, like to come in – we came in just a minute ago when the lights were all dark, and we couldn’t see anything, and we knew the paintings were there but did they have that power? And oddly enough sitting here in the dark when I couldn’t see them, it took my eyes a few minutes to adjust, I still felt like they did, it was like they were zinging off the walls – it was like this buzz…

Jacob Sam La-Rose: You demand that we remain constant. When sound folds itself into empty vaults of air and the last light fades like the dying echo of final footfall, we exhale…

Joe Maciejczek: Well in the morning, about five o’ clock, it’s still kind of quietish. You can start hearing the birds outside actually chippering, chippering, maybe it’s their breakfast time, but you actually can hear them, and the next minute you get the buzzing noise – buzzzzz – on the door and guess what’s coming in – the karma is gone, everything’s gone, it’s bells ringing, phones ringing, and that’s the cleaners, the contractors, the people who repair the doors. It’s like there’s a load of bees in the air, everything is busy, and you get the feeling that the paintings are getting very busy and they’re getting very tired, and they’re waiting for me to get here at 8 ‘o’ clock and give them some free space, and free them.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): The National Gallery podcast. If you’d like to visit the ‘Renoir Landscapes’ exhibition before it closes on 20 May, or attend the special late opening on 19 May, you can reserve tickets in advance at www.nationalgallery.org.uk. With thanks to Marina Warner, Tracy Chevalier, Joe Maciejczek, and Atmaram Kawal.’The Paintings at Night’ was written and performed by Aoife Mannix, and ‘We’ was written and performed by Jacob Sam La-Rose. If you’d like to hear more poems inspired by the National Gallery after dark you can download the bonus track that accompanies this episode.