Episode 23

The National Gallery Podcast

In the September 2008 podcast, bombs, buns and Beethoven - wartime at the National Gallery in this month's podcast. Plus curator Lois Oliver on the Love exhibition, and two beautiful panel paintings reunited and restored.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Hello. I’m Miranda Hinkley and this is the National Gallery Podcast.

Coming up: art gallery with GSOH, central London pad, and extensive holdings would like to meet non-smoking gallery-goer for fun, romance and possible LTR. Make a date to visit the Love exhibition, open throughout the month. And, back together at last, a pair of priceless panels is reunited after decades apart. We pay a visit to the Conservation team to find out more.

The Gallery in wartime

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): But we start this month with an empty Gallery. Bombing is expected any moment and the Government has forbidden large groups of people to gather in one place. Theatres, cinemas and concert venues have closed in what’s being called ‘a cultural blackout’, and the National Gallery’s paintings have been evacuated far away. It’s 1939, and what happens next is the subject of a new book and DVD by author and National Gallery picture researcher Suzanne Bosman. We asked her and archivist Alan Crookham to tell us more.

[The sound of sirens]

Suzanne Bosman: The paintings were moved out of the Gallery just before war was declared over a period of 10 days and on 2 September, all the paintings that were going to be evacuated had left London.

Alan Crookham: The paintings were scattered over several sites in Wales, one in Gloucestershire, and then they became slightly concerned after the fall of France in 1940 that the paintings that had been evacuated to Wales weren’t as secure as they thought they were because they were stored in country houses, in university halls of residence, so they were still stored above ground. So they therefore dispersed the paintings further – that was their initial response – but what they did for a more long-term solution was to look for an underground storage site. So Ian Rawlings who was the Chief Scientific Officer here in the Gallery at the time, he found a location in north Wales near Ffestiniog, a quarry, a slate quarry called Manod, and that seemed to offer the solution. The Government agreed – they agreed to pay for its conversion. They had to… I think they had to widen the entrance, and then they had to build little brick storerooms inside the caves to protect the paintings and in order to also provide them with a stable environment. And they moved the paintings up to Manod in 1941 and that’s pretty much where they stayed until 1945.

Suzanne Bosman: Kenneth Clark, the director at the time, was walking through the empty, forlorn galleries, with all the frames leaning against the walls without their famous masterpieces and he recounted how he was really depressed on seeing this site and especially on the thought that he was going to have to give over the building to some anonymous war ministry for the filling of envelopes and the typing of reports. So imagine his joy when he had an unexpected visit in those first days of the war, when Myra Hess, the famous pianist, came to see him with a revolutionary idea. She suggested organising a weekly concert to take place in the Gallery, so the concerts began only a few weeks after the war was declared.

They were organised in a record number of days and in fact the first one was performed in October. And the first concert was an absolute roaring success. As a result of the concerts and the huge number of people that were attracted in to attend them, the Gallery authorities, and Kenneth Clark in particular, realised that they had a huge audience here and wasn’t it a shame that there was nothing else for them to see in the Gallery. And so the idea of temporary exhibitions was born.

Alan Crookham: In late 1941, the Gallery acquired a Rembrandt, the ‘Margaretha de Geer’, and somebody wrote to ‘The Times’, Charles Wheeler, wrote to ‘The Times’, and he said: ‘why can’t we see this painting? Why can’t we have it on display? Wouldn’t it be worth the risk just to show one painting?’ So they brought back that painting and they put that on display and it was such a success that they also followed on Charles Wheeler’s other suggestion, which was to bring back one painting at a time and they began a series of exhibitions called the ‘Picture of the Month’ in which they brought back one painting, one masterpiece. It was usually on display for about a month and became very popular throughout the war and that carried on right up until 1945, until the day before VE day, it was the last painting of the month, which was Renoir’s ‘The Umbrellas’.

[The sounds of bombs falling]

Suzanne Bosman: Situated centrally in London as it was, the Gallery obviously was a focus of attention, but also very vulnerable to attack. One of the most serious hits on the Gallery occurred on 12 October, 1940, and a 500 lb bomb hit Room 26, which is now Room 10, where we are now standing. There are photographs that show the damage, and when one thinks that the Raphaels hung here before the war, one can only be grateful to the Gallery authorities for having conducted the evacuation so successfully a year before.

Alan Crookham: I think it’s also interesting that throughout the concerts and the acquisitions, there was never any thought of anti-German feeling, I don’t think. I mean, there was never… it was perfectly ok to play Bach, it was perfectly ok to play Beethoven, it was absolutely right that we should have Dürer as a picture of the month – a nice contrast maybe to the attitudes of the Nazi authorities, who of course were quite terrible to their museum curators, and in fact, many of their museum curators fled abroad, because they weren’t allowed to display the paintings that the Nazis didn’t agree with and they weren’t allowed to acquire those paintings and were put under pressure to display only those works that were following the party line.

Suzanne Bosman: I think we can say that the Gallery did have a good war, and I think to many people the National Gallery did come to signify a continuation of the normal life that people had lived before the war and also the fact that it was business as usual. The story of the National Gallery during the war is obviously not an unknown story, but what first attracted me to the subject was the quality of the photographs, especially the photographs of the mines in Wales, where the paintings were kept. Seeing these photographs with the paintings piled up two or three rows high – these priceless masterpieces cheek by jowl – really did attract me from the visual point of view. And I started to look into what else was available and of course found that there were marvellous photographs of the canteen, of the concerts, of the exhibitions, of the bomb damage, which was considerable, and I realised there was this huge seam of material here to accompany a truly marvellous story.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Thanks to Suzanne Bosman and Alan Crookham. Suzanne’s book and DVD, ‘The National Gallery in Wartime’, are available from mid-September; copies will be on sale in the Gallery’s shops. And you might also like to know that we’ll be holding a special day of concerts and events on 25 November to celebrate Dame Myra Hess’s wartime recitals. You can find more information online at www.nationalgallery.org.uk.

'Love' exhibition

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): It’s a cliché, but it’s true: galleries are a good place to flirt. We don’t admit it very often, but we know that some visitors are more interested in making eyes at each other than the paintings. If that’s you – or even if it isn’t – you might like to know that the subject of one of our current exhibitions is erotic, spiritual, devoted, sometimes unrequited, love. The Love exhibition spans the ages to bring together the paintings of Chagall, Vermeer and Raphael, with works by Grayson Perry, Tracy Emin, Marc Quinn and other contemporary artists. Curator Lois Oliver told me more.

Lois Oliver: One of the most fascinating things about working on this exhibition has been that many of these works have a particularly personal meaning for the artist who created them, and this is certainly the case here. It’s a painting by William Holman Hunt and it illustrates the story of Isabella, as told by Boccaccio and Keats. It is rather a macabre story. Isabella’s beloved Lorenzo has been murdered by her brothers, who disapprove of him and she goes to his grave and she takes his head from the grave, and she buries it under a basil plant, which she keeps watered with her tears.

Holman Hunt completed this work a few months after his beloved wife Fanny had died following complications in childbirth, and so the painting is very much a monument to his love for Fanny, but also his grief at her loss. He wrote to his friend William Michael Rossetti, that the only way in which he could deal with the burden of his grief, was to go to his studio everyday, setting out at eight o’ clock in the morning, not coming back until half past five, and working really hard at this painting. And he had said that one of the things that made it easier, was that Fanny had been so involved in this particular project from the start. She had actually modelled for some early compositional sketches for the painting and there’s so much about it… you can see there are many reminders of death… this basil is growing out of a wonderful majolica pot which is decorated with skulls; it’s also got two hearts pierced with arrows and there are the wilted roses on the ground suggesting the separation of the couple and the ending of earthly love.

But it’s also very much a monument to the way in which love endures beyond death, and this pot is sitting on a wonderful embroidered altar cloth, and all around it is a quotation from the Song of Solomon. You can see Lorenzo’s name picked out in the centre, but also there’s a quotation around the corner – it’s the part which says that love is strong as death.

Miranda Hinkley: There’s another work here in the exhibition, Lois, which you’re going to show me now, which is sort of… also has that sense of wanting to protect your loved ones from harm.

Lois Oliver: Yes, it’s a particularly poignant piece that’s by the sculptor Grayson Perry, and it’s a tiny, fragile ceramic hare, a really delicate piece. And it’s inscribed all over: ‘God, please keep my children safe’. It suggests the father’s all-consuming love for his children, but also a parent’s anxiety that perhaps their love is not enough to keep their children safe from all of the dangers of the world. And in the very size of the piece, it suggests the vulnerability of childhood.

It reminds me of those objects you sometimes find left in holy places requesting divine intervention. When you set it alongside some of the older works in the exhibition that are all about divine love – we have paintings by Raphael, by Bassano, by Gruchino and by Murillo – and they date from a time of much greater religious certainty and confidence in divine protection, and the contrast with the little piece by Grayson Perry is I think very moving.

Miranda Hinkley: It certainly does look very fragile doesn’t it? And it’s got these very long slender ears, which look as if they could just snap off very easily.

Lois Oliver: They do. It’s a very beautiful piece, I think.

Miranda Hinkley: Well, there’s a final piece here, that we’re not actually going to show you, but we will briefly invite you to come and see, which is the Yoko Ono conceptual piece.

Lois Oliver: Yes, this is a new piece called ‘Secret Piece Number Three’ and here you’re invited to come and be the artist. Yoko invites us to put a picture of somebody that we love on the canvas, or write a message to someone we love onto the canvas. Of course, we don’t know quite what shape this is going to take yet, but certainly I think it will convey something of the very individual but also universal nature of love.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Curator Lois Oliver. Well, Yoko Ono’s exhibit is doing a brisk trade, but there’s still room if you’d like to add your own note or picture to the display – my favourite contribution so far is a receipt for a puppy. Admission is free and the exhibition is open until 5 October.

'The Virgin and Child' and 'The Man of Sorrows' reunited

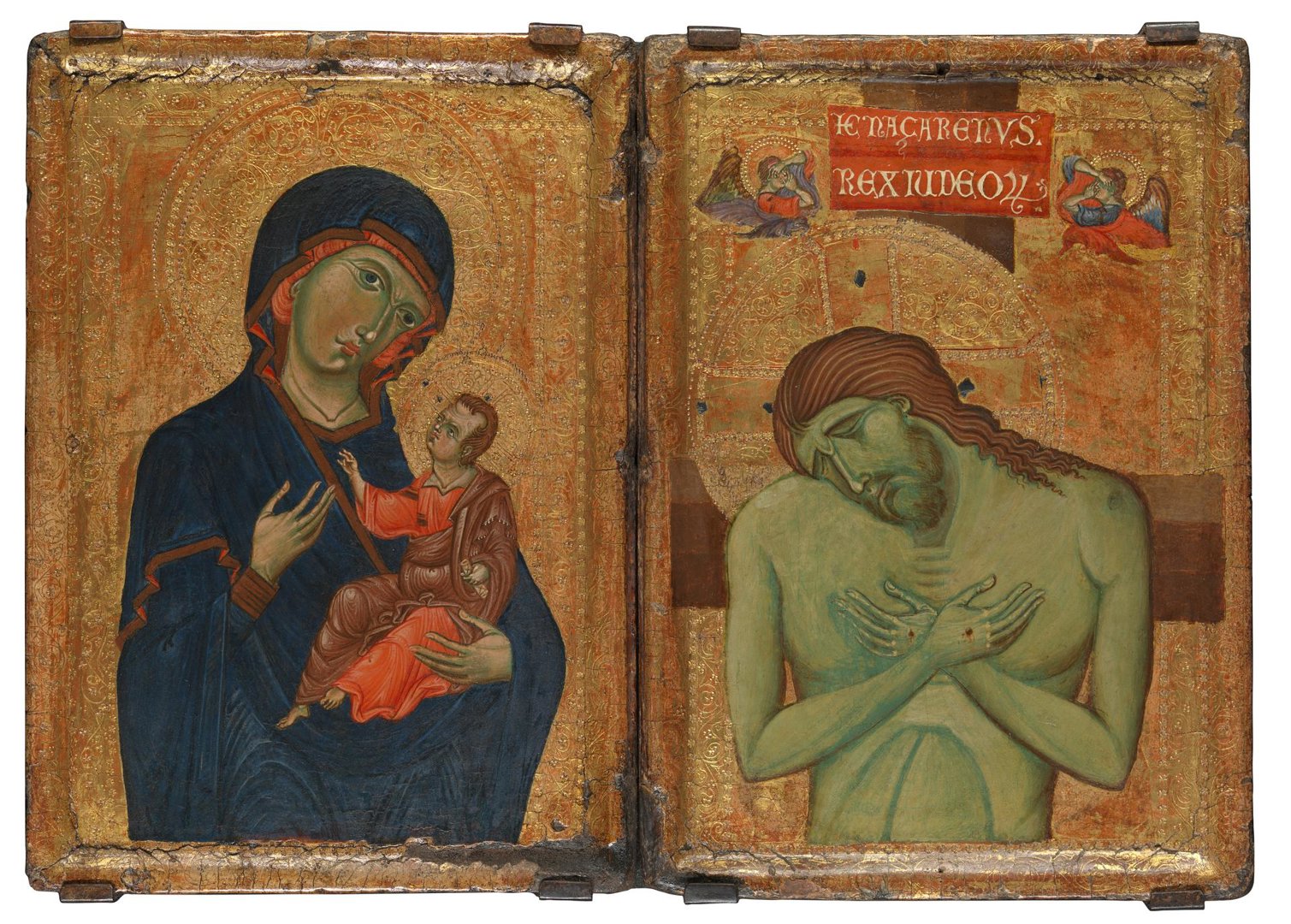

Miranda Hinkley: This month’s final segment takes us to the Conservation studio to meet curator Dillian Gordon and head of Conservation Martin Wyld. They’ve been working on two exquisitely painted panels from the 13th century – The Virgin and Child and The Man of Sorrows – which have a lot more in common than anyone, until recently, thought.

Dillian Gordon: This was a very exciting occasion for the National Gallery. A photograph of ‘The Virgin and Child’ had been sent to Joanna Cannon at the Courtauld Institute and she recognised that it belonged with ‘The Man of Sorrows’, which at some stage of its life has been thought to be Venetian. She’s a friend of mine and when I heard about this I thought it would be an exciting opportunity for the Gallery to acquire these panels because we have very few paintings of the 13th century.

It was always going to be a complicated process because the two panels were obviously in different collections and they hadn’t been together for probably over 100 years. So we were hoping that the owners of each panel would agree to sell to the National Gallery and we could bring the two panels together. And there was a very exciting period over Christmas 1998 to January 1999 when we were negotiating and finally we were successful and the two panels came together.

And of course there’s absolutely no question that they belong together. The backs are painted with imitation porphyry with hooks which definitely fit together and on the front you can see that the punching on both is identical. And the virgin is gesturing towards her child and looking sorrowfully out at the spectator, knowing that the child will be crucified and that he will end up as ‘The Man of Sorrows’ on the Cross.

Miranda Hinkley: So you’ve sort of got life and death on one side and the other.

Dillian Gordon: Yes, very much so. The child, infant Christ as a baby in his mother’s arms, and then the adult Christ with his arms folded in suffering outlined against the Cross, and the angels above are covering their faces in mourning.

Miranda Hinkley: Dillian, you mentioned that originally it had been thought that figure of Christ was thought to be of Venetian origin; has the process of reuniting these panels shed new light on their origin?

Dillian Gordon: Yes, that’s another very exciting aspect. ‘The Virgin and Child’ is unquestionably Umbrian and by putting the two together and realising that in fact ‘The Man of Sorrows’ is Umbrian as well, there are several comparative examples of Umbrian painting, particularly of course with crucifixes, where we can show it’s an Umbrian painter. It’s, of course, an anonymous painter and we don’t know who it was painted for. It’s an object for private devotion. It would have been something that you could perhaps slip into a leather case and travel around with and then open and use for your private prayer. One of the most unusual aspects of this painting is the very elaborate punching that you have all up the borders and around the Virgin’s halo. It’s extremely delicate and, as I say, unusual, for a 13th-century painting at this stage. It becomes much more common in later paintings.

Miranda Hinkley: Very, very delicate isn’t it? You’ve got floral motifs and intertwining plant forms and stems curling round, but each one is very, very delicately done. How would that have been rendered?

Dillian Gordon: The artist would have had an iron tool which he would strike into the gold leaf and depending on the pressure the result would be very slightly different, so sometimes the punches look slightly different but they’ve been made with the same tool.

Miranda Hinkley: Well, when this piece arrived here at the National Gallery, it was in quite a different state to the condition it’s in now. Martin Wyld, you’ve been working on it here in Conservation. Tell us about the condition it was in when it arrived.

Martin Wyld: Well, we could see that it was in very good condition, but it was quite obscured by probably several hundred years worth of varnish and wax polish and dirt settling on it, and at some point when the panels were still together, we think that someone had tried to clean up the figures of Christ and the Virgin and Child and they seem to have pushed all the dirt into the punch marks and incised lines, so instead of having a sort of sparkly punch-marked and incised background, they were like a series of sort of black full stops all over it, and that was the main difference.

Miranda Hinkley: And how have you worked to clean that off?

Martin Wyld: Well, I had to do most of the work under a microscope because as you can see some of the punch marks are about a millimetre across. I’ve been able to use some sort of white spirit and solvent mixed together to soften the black deposits in the punch marks, and then scrape them out with a sharpened stick, working under a microscope at about 15 times magnification. It has taken quite a long time, but I think it’s been well worth it.

Miranda Hinkley: Originally these would have been hinged together so that you could actually close the whole thing up like a book. When you’ve finished the cleaning process how is it going to be presented to people?

Martin Wyld: As they were before, which is they’ll be clamped to a padded backboard right next to each other, which is how they would have originally been seen.

Miranda Hinkley: Well, it’s very exciting to have such exquisite workmanship reunited so visitors can see it as it would have originally been.

Dillian Gordon: You’re quite right. There’s nothing like it in the collection and, indeed, really there’s nothing like it surviving in the world. There are comparatively few 13th-century paintings still surviving in private hands, so we were extremely lucky to be able to buy this. These are objects which in their own right as independent panels are very beautiful and of course reuniting them has made them an object which is absolutely unique.

Miranda Hinkley (in the studio): Thanks to Dillian Gordon and Martin Wyld. The reunited diptych will be back in the Gallery from 15 September for a few weeks before it goes on loan. You can come along and see it and any of the other pictures we’ve talked about it any day of the week, from 10 till 6, and 10 till 9 on Wednesdays. Until next time – goodbye!