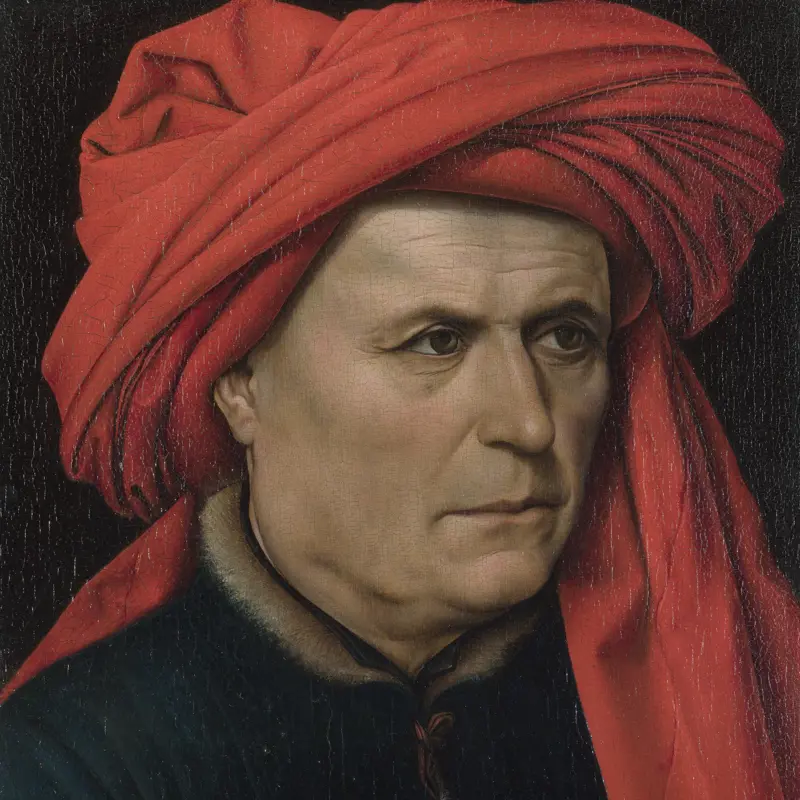

Robert Campin, 'A Man', about 1435

About the work

Overview

This striking portrait of a man in a red hat forms a pair with Campin’s A Woman – the sitters were clearly husband and wife. We do not know who they were, but their clothes suggest they were prosperous townsfolk, perhaps from Tournai where Campin lived and worked.

Campin has arranged the older husband’s clothes and face to convey his character: he seems world-weary, uncertain and disillusioned. His face is dimly lit and his skin sags beneath his jaw and forms crow’s feet around his dull eyes. He slouches. His head is off centre, and his hat has been brought forward so it seems to press down on his head.

Instead of looking out at us he gazes across at his wife. The shadows cast on his face stress the falling lines of the pattern Campin has created. His hands are not included, perhaps because they would have been at odds with this pattern.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- A Man

- Artist

- Robert Campin

- Artist dates

- 1378/9 - 1444

- Part of the series

- A Man and a Woman

- Date made

- About 1435

- Medium and support

- Oil on wood (Baltic/Polish oak, identified)

- Dimensions

- 40.7 × 28.1 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1860

- Inventory number

- NG653.1

- Location

- Room 52

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 21st-century Replica Frame

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Lorne Campbell, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools’, London 1998; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Bibliography

-

1833F. Campe, Neues Maler-Lexicon zum Handgebrauch für Kunstfreunde, Nuremberg 1833

-

1849Christie & Manson, Catalogue of the Valuable and Highly Interesting Collection of Italian, German, and Flemish Pictures, Formed by … Doctor Frederick Campe of Nuremburg, London, 18 May 1849

-

1858J.D. Passavant, 'Die Maler Rogier van der Weyden', Zeitscrift für christliche Archäologie und Kunst, II, 1858, pp. 1-20, 120-30, 178-80

-

1861R.N. Wornum, Descriptive and Historical Catalogue of the Pictures in the National Gallery, London 1861

-

1887W. Bode, 'La renaissance au musée de Berlin', Gazette des beaux-arts, XXXV, 1887, pp. 204-20

-

1888E.T. Cook, A Popular Handbook to the National Gallery Including, by Special Permission, Notes Collected from the Works of Mr. Ruskin, London 1888

-

1889National Gallery, Descriptive and Historical Catalogue of the Pictures in the National Gallery with Biographical Notices of the Painters: Foreign Schools, London 1889

-

1893H. von Tschudi, 'Berichte und Mitteilungen aus Sammlungen und Mun über Staatliche Kunstpflege und Restaurationen. London. Die Ausstellung altniederländische Gemälde im Burlington Fine Arts Club', Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft, XVI, 1893, pp. 100-16

-

1898H. von Tschudi, 'Der Meister von Flémalle', Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen, XIX, 1898, pp. 8-34, 89-116

-

1899E. Firmenich-Richartz, 'Rogier van der Weyden, der Meister von Flémalle. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Vlämischen Malerschule', Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, X, 1899, pp. 1-12, 129-44

-

1904M.H. Witt, The German and Flemish Masters in the National Gallery, London 1904

-

1906K. Voll, Die altniederländische Malerei von Jan Van Eyck bis Memling - Ein entwicklungsgeschichtlicher Versuch, Leipzig 1906

-

1913F. Winkler, Der Meister von Flémalle und Rogier van der Weyden, Strasbourg 1913

-

1915National Gallery, National Gallery: Abridged Descriptive and Historical Catalogue of the British and Foreign Pictures, London 1915

-

1916E. Firmenich-Richartz, Die Brüder Boisserée, I. Sulpiz und Melchior Boisserée als Kunstsammler, Jena 1916

-

1918S. Reinach, 'Le Maître de Flémalle', Bulletin archéologique du Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques, 1918, pp. 74-90

-

1921W.M. Conway, The van Eycks and Their Followers, London 1921

-

1924M.J. Friedländer, Die altniederländische Malerei, 14 vols, Berlin 1924

-

1925C.J. Holmes, Old Masters and Modern Art: The National Gallery, the Netherlands, Germany and Spain, London 1925

-

1928J. Destrée, 'Le maître dit de Flémalle: Robert Campin', Revue de l'art ancien et moderne, LIII, 1928, pp. 3-14, 81-92, 137-52

-

1928A. Scmarsow, 'Robert van der Kampine und Roger van der Weyden: Kompositionsgesetze des Mittelalters in der Nordeuropäischen Renaissance', Abhandlungen der Philologisch-historischen Klasse der Sächsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, XXXIX/2, 1928, pp. 47-52, 156-8

-

1931E. Renders, La solution du problème van der Weyden-Flémalle-Campin, Bruges 1931

-

1932A. Burroughs, 'Campin and van der Weyden Again', Metropolitan Museum Studies, IV, 1932, pp. 131-50

-

1934R.N.D. Wilson, The National and Tate Galleries, London 1934

-

1937M. Davies, 'National Gallery Notes, III: Netherlandish Primitives: Rogier van der Weyden and Robert Campin', The Burlington Magazine, LXXI/414, 1937, pp. 140-5

-

1939C. de Tolnay, Le Maître de Flémalle et les frères Van Eyck, Brussels 1939

-

1945Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: Early Netherlandish School, London 1945

-

1953M. Davies, The National Gallery, London, Les Primitifs flamands. I, Corpus de la peinture des anciens Pay-Bas méridionaux au quinzième siècle 3, 2 vols, Antwerp 1953

-

1953E. Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character, Cambridge 1953

-

1955Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: Early Netherlandish School, 2nd edn (revised), London 1955

-

1962E. Reynst, Friedrich Campe und seine Bilderbogen Verlag zu Nürnberg, Veröffentlichungen der Stadtbibliothek 5, Nuremberg 1962

-

1966M.S. Frinta, The Genius of Robert Campin, The Hague 1966

-

1966R. Messerer, Briefweschel zwischen Ludwig I. von Bayern und Georg von Dillis, Munich 1966

-

1967M.J. Friedländer, Early Netherlandish Painting, eds N. Veronée-Verhaegen and H. Pauwels, trans. H. Norden, 14 vols, Leiden 1967

-

1971M. Comblen-Sonkes, 'Le dessin sous-jacent chez Roger van der Weyden et le problème de la personnalité du Maitre de Flémalle', Bulletin de l'Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique, XIII, 1971, pp. 161-206

-

1979L. Campbell, Van der Weyden, London 1979

-

1980M. Scott, Late Gothic Europe: 1400-1500, London 1980

-

1982J. Huvelle, La vie et l'oeuvre de Roger de le Pasture van der Weyden, Tournai 1399 - Bruxelles 1464, Mons 1982

-

1986M. Scott, A Visual History of Costume: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, London 1986

-

1987Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Early Netherlandish School, 3rd edn, London 1987

-

1988National Gallery, 'Pictures Cleaned and Restored in the Conservation Department of the National Gallery, 1987', National Gallery Technical Bulletin, XII, 1988

-

1988D. Saunders, 'Colour Change Measurement by Digital Image Processing', National Gallery Technical Bulletin, XII, 1988, pp. 66-77

-

1990L. Campbell, Renaissance Portraits: European Portrait-Painting in the 14th, 15th and 16th Centuries, New Haven 1990

-

1990A. Dülberg, Privatporträts: Geschichte und Ikonologie einer Gattung im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert., Berlin 1990

-

1991J. Dunkerton et al., Giotto to Dürer: Early Renaissance Painting in the National Gallery, New Haven 1991

-

1991M. Wilson, A Guide to the Sainsbury Wing at the National Gallery, London 1991

-

1994H. Belting and C. Kruse, Die Erfindung des Gemäldes: Das erste Jahrhundert der niederländischen Malerei, Munich 1994

-

1994E. Langmuir, The National Gallery Companion Guide, London 1994

-

1994O. Pächt, Van Eyck and the Founders of Early Netherlandish Painting, London 1994

-

1996C. Stroo et al., The Flemish Primitives: Catalogue of Early Netherlandish Painting in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, 6 vols, Brussels 1996

-

1996L. Campbell, 'Campin's Portraits', in S. Foister and S. Nash (eds), Robert Campin: New Directions in Scholarship, Turnhout 1996, pp. 123-35

-

1997S. Kemperdick, Der Meister von Flémalle: Die Werkstatt Robert Campins und Rogier van der Weyden, Turnhout 1997

-

1997J. Richardson, Looking at Pictures: An Introduction to Art for Young People Through the Collection of the National Gallery, London 1997

-

1998Campbell, Lorne, National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings, London 1998

-

1999D. de Vos, Rogier van der Weyden: The Complete Works, Antwerp 1999

-

2000T. Todorov, Éloge de l'individu: Essai sur la peinture flammande de la Renaissance, Paris 2000

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

Frame

This replica frame was made at the Gallery in 2006. It was inspired by the original frame on Jan van Eyck’s Margaret, the Artist’s Wife, of 1439 (Groeningemuseum, Bruges). While the Van Eyck frame was executed in marble, the oak replica was water-gilded and deliberately distressed. The top fillet is followed by an ogee and is edged by a small hollow. The back edge is marbled.

It is possible that Campin’s A Man and A Woman were once hinged together to form a diptych, although any physical evidence of this has been lost. Both portraits feature traces of green pigment at their edges, probably remnants of the frame, also now lost.

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the series: A Man and a Woman

Overview

A man and a woman, clearly husband and wife, gaze towards each other. We don‘t know who they were, but their clothes, which are not excessively rich, suggest that they were relatively prosperous townspeople. The clarity and credibility of these portraits, which were designed as a pair, is astonishing – but they do more than reflect how the sitters looked.

Campin’s ability to convey textures of skin, fur and fabric means that we are not immediately aware of the skill with which he arranged the sitters’ clothes and even their features. These are highly ordered geometric compositions devised to show us what the couple were like: an older, world-weary man and a bright, optimistic young woman. The man slouches and the drooping lines of his face are echoed by his clothes; the woman’s skin is smooth, her eyes are bright and her features and clothes form rising lines.