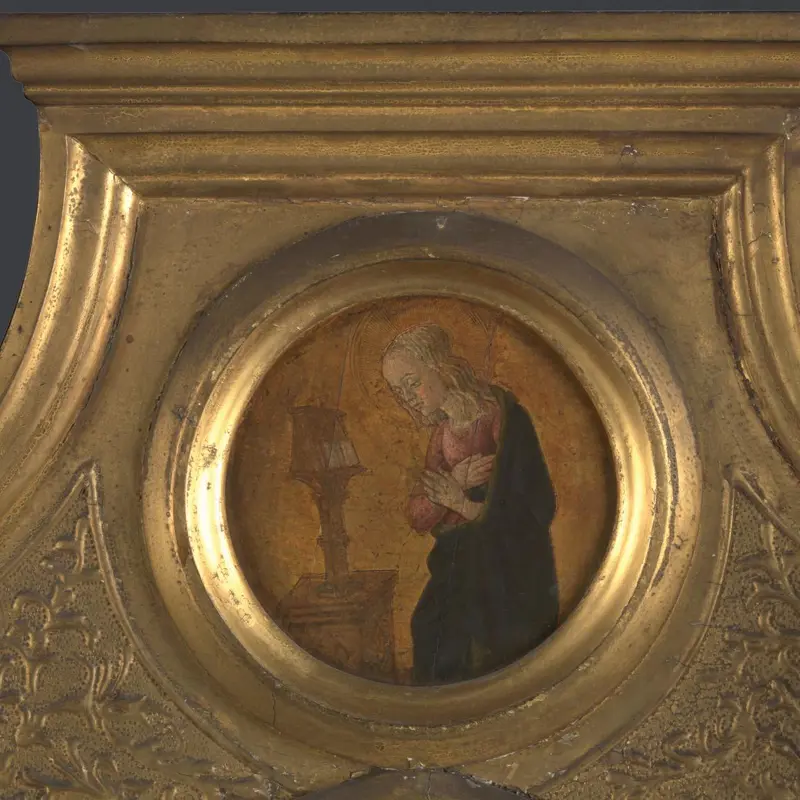

Probably by Jacopo di Antonio (Master of Pratovecchio?), 'The Virgin: Altarpiece Pinnacle (Left)', about 1450?

About the work

Overview

This small, arched painting of the Virgin Mary grieving comes from a large polyptych (a multi-panelled altarpiece) painted in around 1450 for a provincial house of Camaldolese nuns in Pratovecchio, Tuscany. A number of other panels from this altarpiece are also in the National Gallery’s collection. This one would have been at the top, to the left of an image of the Crucifixion (now missing).

In contrast with the rest of the polyptych, and most early Renaissance altarpieces, the Virgin stands against a dark background rather than one of burnished gold. This is not original, however – it would have originally been gold like the other panels.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Virgin: Altarpiece Pinnacle (Left)

- Artist

- Probably by Jacopo di Antonio (Master of Pratovecchio?)

- Artist dates

- 1427 - 1454

- Part of the group

- Pratovecchio Altarpiece

- Date made

- About 1450?

- Medium and support

- Egg tempera on wood (probably poplar)

- Dimensions

- 57 × 27.5 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1857

- Inventory number

- NG584.7

- Location

- Not on display

- Collection

- Main Collection

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Dillian Gordon, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings’, vol. 1, London 2003; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2022Donatello, the RenaissancePalazzo Strozzi19 March 2022 - 31 July 2022

Bibliography

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2003Gordon, Dillian, National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings, 1, London 2003

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the group: Pratovecchio Altarpiece

Overview

This altarpiece is a polyptych (a multi-panelled altarpiece) but parts of it are missing. The two halves were not originally next to each other, but were on either side of a painting of the Assumption of the Virgin formerly in the church of San Giovanni Evangelista, in Pratovecchio, Tuscany.

The whole altarpiece once stood on a side altar in the Camaldolese nunnery of San Giovanni. Very unusually we know quite a lot about its commissioning. In June 1400 one Michele di Antonio Vaggi, a Camaldolese monk, made a will asking his mother Johanna to found a chapel at San Giovanni, for which she was to provide a ‘tavola picta’ (a painted altarpiece).

Both Johanna and Michele’s patron saints appear in the main panels, with Camaldolese saints in the pinnacles. This is presumably the altarpiece made for their family chapel, although it wasn't painted until the 1450s.