Master of the Aachen Altarpiece, 'The Crucifixion', 1489-96

About the work

Overview

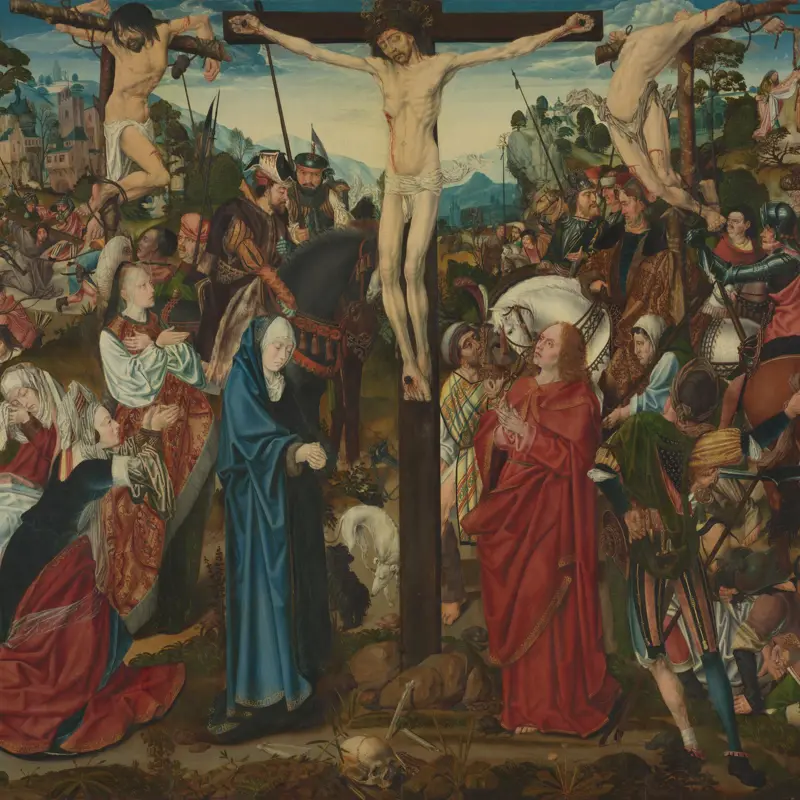

This is the central panel of a triptych (a painting in three parts) that was made for the church of St Columba, Cologne. Its two side panels – or shutters – are in the collection of the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

A small group mourns the crucified Christ: the Virgin Mary, his mother, stands at the foot of the Cross with three distraught holy women, opposite a red-eyed Saint John the Evangelist. Christ has been nailed to the Cross, while the two thieves crucified alongside him have been tied up with rope. The contorted poses of their bodies suggest the agony of the torture they are enduring, while Christ’s body is serene in death.

Among the crowd on the left, Christ is shown before the Crucifixion, collapsing under the weight of his cross as he carries it to the site of his execution. The upper right of the panel shows his body being removed from the Cross.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Crucifixion

- Artist dates

- Active late 15th to early 16th century

- Part of the group

- The Crucifixion Altarpiece

- Date made

- 1489-96

- Medium and support

- Oil on wood (probably oak)

- Dimensions

- 107.3 × 120.3 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Presented by Edward Shipperdson, 1847

- Inventory number

- NG1049

- Location

- On loan: Long Loan to the Walker Art Gallery (2023 - 2026), Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, UK

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Previous owners

Provenance

Probably from the church of St Columba in Cologne, where the donor, Hermann Rinck (died 1496) was buried and where a painting on the altar of the cross recorded there in the eighteenth century included the portraits and coats of arms of Hermann Rinck and his wife, Gertrud van Dalen.

A letter in the NG archives from Edward Shipperdson (died 1856), who presented the picture to the National Gallery in 1847, states that the painting was brought from Flanders to England at the time of the French Revolution. It is not known if it was then still with its shutters, which are first recorded when acquired by the Liverpool Royal Institute from an unknown source between 1836 and 1843. According to Shipperdson, NG 1049 was formerly with ‘James’ at Manchester, who had brought the painting to England. The latter sold it to a Mr Dixon, a merchant of Newcastle, possibly to be identified with Joseph Dixon, an iron merchant of Watergate, Sandhill. Shipperdson bought the picture from Dixon’s executors on his death and presented it to the Gallery in 1847, as a Crucifixion by the German engraver Heinrich Aldegrever.

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Susan Foister, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The German Paintings before 1800’, London 2024; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

1988Long Loan to the Walker Art Gallery (1988 - 2011)Walker Art Gallery1 December 1988 - 27 January 2011

-

2014Strange Beauty: Masters of the German RenaissanceThe National Gallery (London)19 February 2014 - 11 May 2014

-

2014Long Loan to the Walker Art Gallery (2014 - 2017)Walker Art Gallery12 May 2014 - 11 May 2017

-

2019Long Loan to the Walker Art Gallery (2019 - 2020)Walker Art Gallery1 March 2019 - 24 February 2020

-

2023Long Loan to the Walker Art Gallery (2023 - 2026)Walker Art Gallery3 July 2023 - 2 July 2026

Bibliography

-

1900M.J. Friedländer, 'Die Leihausstellung der New Gallery in London, Januar - März 1900. Hauptsächlich niederländische Gemälde des XV. und XVI. Jahrhunderts', Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft, 1900

-

1902C. Aldenhoven, Geschichte der Kölner Malerschule, Lübeck 1902

-

1924H. Brockmann, Die Spätzeit der Kölner Malerschule, Bonn 1924

-

1924M.J. Friedländer, 'Der Kölnische Meister des Aachener Altars', Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, I, 1924, pp. 101-8

-

1934A. Stange, Deutsche Malerei der Gotik, 11 vols, Munich 1934

-

1940C.P. Baudisch, Jan Joest von Kalkar, Bonn 1940

-

1954H. Kisky, 'Der Kölner Meister des Aachener Altares und der Harenrathkapelle an St. Maria im Kapitol', Annalen des historischen Vereins für den Niederrhein, 155-156, 1954, pp. 530-62

-

1959Levey, Michael, National Gallery Catalogues: The German Schools, London 1959

-

1961P. Pieper, Kölner Maler der Spätgotik: Der Meister des Bartolomäus-Altares: Der Meister des Aachener Altares (exh. cat. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, 25 March - 28 May 1961), Cologne 1961

-

1963J. Jacob, 'The Master of the Aachen Altarpiece: A Discovery', Bulletin: Walker Art Gallery, XI, 1963, pp. 7-21

-

1964T. Rensing, 'Der Meister des Aachener Altares', Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, XXVI, 1964, pp. 229-34

-

1967A. Stange, Der deutschen Tafelbilder vor Dürer. Kritisches Verzeichnis, Munich 1967

-

1968F. Anzelewsky, 'Zum Problem des Meisters des Aachener Altares', Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, XXX, 1968, pp. 185-200

-

1977E. Morris and M. Hopkinson, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool: Foreign Catalogue, Liverpool 1977

-

1977A. Smith, Late Gothic Art from Cologne (exh. cat. The National Gallery, 5 April - 1 June 1977), London 1977

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2024S. Foister, National Gallery Catalogues: The German Paintings before 1800, 2 vols, London 2024

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the group: The Crucifixion Altarpiece

Overview

This altarpiece was commissioned by the family of Hermann Rinck, who was burgomaster (or mayor) of Cologne three times in the 1480s, after his death in around 1496. It stood on the altar of their family chapel in the church of Saint Columba in the city.

The altarpiece is in the form of a triptych (a painting made up of three panels). Its two side panels – or shutters – are in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. The altarpiece was dismantled and the panels separated some time between 1810 and 1820. The central panel, which is in the National Gallery’s collection, shows Christ’s crucifixion. The shutters show the episodes leading up to the Crucifixion and those that followed it.

When the altarpiece was cleaned in 1963, overpaint on the reverse of the shutters was removed, revealing paintings of Rinck and his wife with three of their sons.