Lorenzo Monaco, 'The Coronation of the Virgin', 1407-9

About the work

Overview

Christ and his mother, Mary, are seated on a throne. He places a crown on her head, and she crosses her hands on her chest in a gesture of acceptance. This is the coronation of the Virgin, a popular subject in medieval Italy where Mary was especially revered. According to medieval Christian legend, her soul was carried up to heaven after her death and she was crowned as Queen of Heaven.

This feast of gold and colour is a perfect example of early Renaissance painting. It was originally at the centre of a large polyptych (multi-panelled altarpiece) painted by Lorenzo Monaco for the monastery of San Benedetto fuori della Porta Pinti in Florence. Other panels from the same altarpiece survive in the National Gallery and in other collections.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Coronation of the Virgin: Central Main Tier Panel

- Artist

- Lorenzo Monaco

- Artist dates

- Active 1399, died 1423 or 1424

- Part of the series

- San Benedetto Altarpiece

- Date made

- 1407-9

- Medium and support

- Egg tempera on wood (probably poplar)

- Dimensions

- 220.5 × 115.2 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1902

- Inventory number

- NG1897

- Location

- Room 57

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 20th-century Replica Frame

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Dillian Gordon, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings’, vol. 1, London 2003; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Bibliography

-

1684F.L. Del Migliore, Firenze città nobilissima, Florence 1684

-

1710G. Farulli, Istoria cronologica del nobile, ed antico monastero degli Angioli di Firenze, Lucca 1710

-

1723P. Farulli and F. Masetti, Teatro storico del sacro eremo di Camaldoli, Lucca 1723

-

1754G. Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine, 10 vols, Florence 1754

-

1791D. Moreni, Notizie istoriche dei contorni di Firenze, 6 vols, Florence 1791

-

1864J.A. Crowe and G.B. Cavalcaselle, A New History of Painting in Italy: From the Second to the Sixteenth Century, 3 vols, London 1864

-

1878G. Vasari, Le vite de'più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori: Con nuove annotazioni e commenti di Gaetano Milanesi, ed. G. Milanesi, 8 vols, Florence 1878

-

1887M.-F. Reiset, Une visite à la Galerie nationale de Londres, 2nd revised edn, Rapilly 1887

-

1893H.A. Grueber and I. Spielmann, Exhibition of Early Italian Art from 1300 to 1550, (exh. cat. New Gallery, 1893-94), London 1893

-

1905O. Sirén, Don Lorenzo Monaco, Strasbourg 1905

-

1923R. van Marle, The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, 19 vols, The Hague 1923

-

1938G. Pudelko, 'The Stylistic Development of Lorenzo Monaco, I', The Burlington Magazine, LXXIII/429, 1938, pp. 237-48

-

1949M. Davies, 'Lorenzo Monaco's "Coronation of the Virgin" in London', Critica d'arte, VIII/29, 1949, pp. 202-8

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1958M.L. D'Ancona, 'Matteo Torelli', Commentari, IX, 1958, pp. 244-58

-

1958M.L. D'Ancona, 'Some New Attributions to Lorenzo Monaco', Art Bulletin, XL/3, 1958, pp. 175-91

-

1961M. Davies, The Earlier Italian Schools, 2nd edn, London 1961

-

1968B. Degenhart and A. Schmitt, Corpus der italienischen Zeichnungen, 1300-1450, Berlin 1968

-

1968A. Conti, 'Quadri alluvionati 1333, 1557, 1966', Paragone, XIX/215, 1968, pp. 3-22

-

1975M. Boskovits, Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370-1400, Florence 1975

-

1975M.-L. Frawley, Lorenzo Monaco and His Patrons, MA Thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art 1975

-

1978L. Bellosi and F. Bellini, I disegni antichi degli Uffizi: I tempi del Ghiberti, (exh. cat. Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi, 21 October 1978 - 4 February 1979), Florence 1978

-

1980G. Schiller, Ikonographie der christlichen Kunst, Gütersloh 1980

-

1982Centro d'Incontro della Certosa di Firenze, Iconografia di San Benedetto nella pittura della Toscana. Immagini e aspetti culturali fino al XVI secolo, Florence 1982

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

1988A. Burnstock, 'The Fading of the Virgin's Robe in Lorenzo Monaco's "Coronation of the Virgin"', National Gallery Technical Bulletin, XII, 1988, pp. 58-65

-

1989M. Eisenberg, Lorenzo Monaco, Princeton 1989

-

1991J. Dunkerton et al., Giotto to Dürer: Early Renaissance Painting in the National Gallery, New Haven 1991

-

1991M.B. Hall, Colour and Meaning: Practice and Theory in Renaissance Painting, Cambridge 1991

-

1991F. Haskell, 'William Coningham and His Collection of Old Masters', The Burlington Magazine, CXXXIII/1063, 1991, pp. 676-81

-

1992M. Warner, 'The Pre-Raphaelites and the National Gallery', in M. Warner et al., The Pre-Raphaelites in Context, San Marino 1992, pp. 1-12

-

1993L. Kanter, 'Review: Marvin Eisenberg, Lorenzo Monaco, 1989', The Burlington Magazine, CXXXV/1086, 1993

-

1994M. Boskovits, 'Su Don Lorenzo, pittore camaldolese', Arte Cristiana, LXXXII, 1994, pp. 351-64

-

1994L. Kanter et al., Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence 1300-1450 (exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17 November 1994 - 26 February 1995), New York 1994

-

1995T. Lamb and J. Bourriaus (eds), Colour: Art and Science, Cambridge 1995

-

1995A. Thomas, The Painter's Practice in Renaissance Tuscany, Cambridge 1995

-

1995D. Gordon, 'The Altar-Piece by Lorenzo Monaco in the National Gallery, London', The Burlington Magazine, CXXXVII/112, 1995, pp. 723-7

-

1995D. Gordon and A. Thomas, 'A New Document for the High Altar-Piece for S. Benedetto Fuori della Porta Pinti, Florence', The Burlington Magazine, CXXXVII/112, 1995, pp. 720-2

-

1998M. Ciatti and C. Frosininis (eds), Lorenzo Monaco: Tecnica e restauro, Florence 1998

-

1998National Gallery, 'The Restoration of Lorenzo Monaco's Altarpiece', National Gallery News, 1998

-

2000P. Ackroyd, L. Keith and D. Gordon, 'The Restoration of Lorenzo Monaco's "Coronation of the Virgin": Retouching and Display', National Gallery Technical Bulletin, XXI/1, 2000, pp. 43-57

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2003Gordon, Dillian, National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings, 1, London 2003

-

2006G.R. Bent, Monastic Art in Lorenzo Monaco's Florence: Painting and Patronage in Santa Maria Degli Angeli, 1300-1415, Lewiston NY 2006

-

2006A. Tartuferi and D. Parenti, Lorenzo Monaco: A Bridge from Giotto's Heritage to the Renaissance, (exh. cat. Galleria dell’Accademia, 9 May - 24 September 2006), Florence 2006

-

2007P.L. Rubin, Images and Identity in Fifteenth-Century Florence, New Haven 2007

Frame

At the Gallery in 1949, Arthur Lucas designed and constructed a frame to reunite three panels from the San Benedetto Altarpiece. This architectural frame has three arched openings and a gabled top. The frame was water-gilded with a craquelure finish.

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the series: San Benedetto Altarpiece

Overview

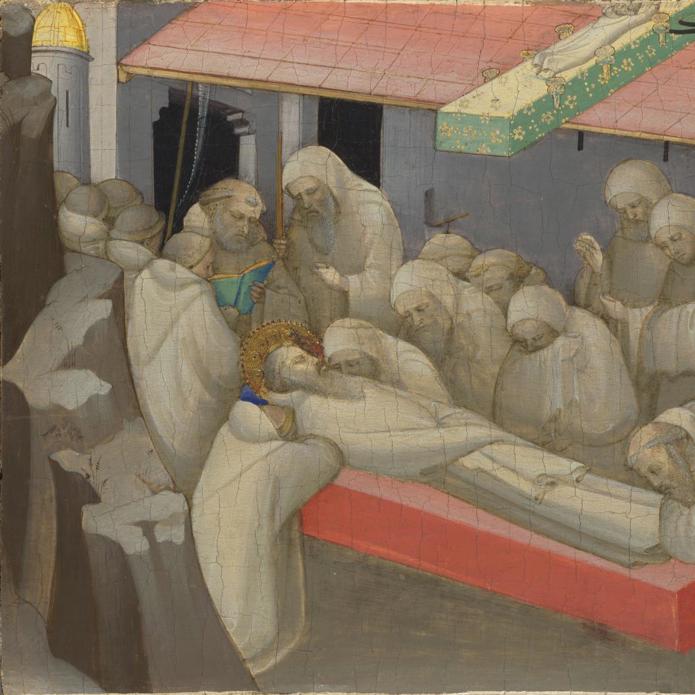

A glorious, glowing, multi-coloured company of saints and angels surround Christ and his mother as he delicately places a golden crown on her head, making her Queen of Heaven. This huge polyptych (multi-panelled altarpiece) was painted for the high altar of the monastery of San Benedetto fuori della Porta Pinti in Florence. It was originally even bigger: its main panels are in the National Gallery, but other parts are scattered in collections across the world.

The Camaldolites (a religious order founded in 1012) were famous for their strict lifestyle, although they lived among great visual riches. The monastery’s register records how it was commissioned by a Florentine citizen, Luca Pieri Rinieri Berri, who was to pay almost the entire cost. In recompense his name was painted on the altarpiece – a few letters can be made out on the grey step of dais – so that he would be remembered in the monks' prayers.