Hans Memling, 'The Donne Triptych', about 1478

About the work

Overview

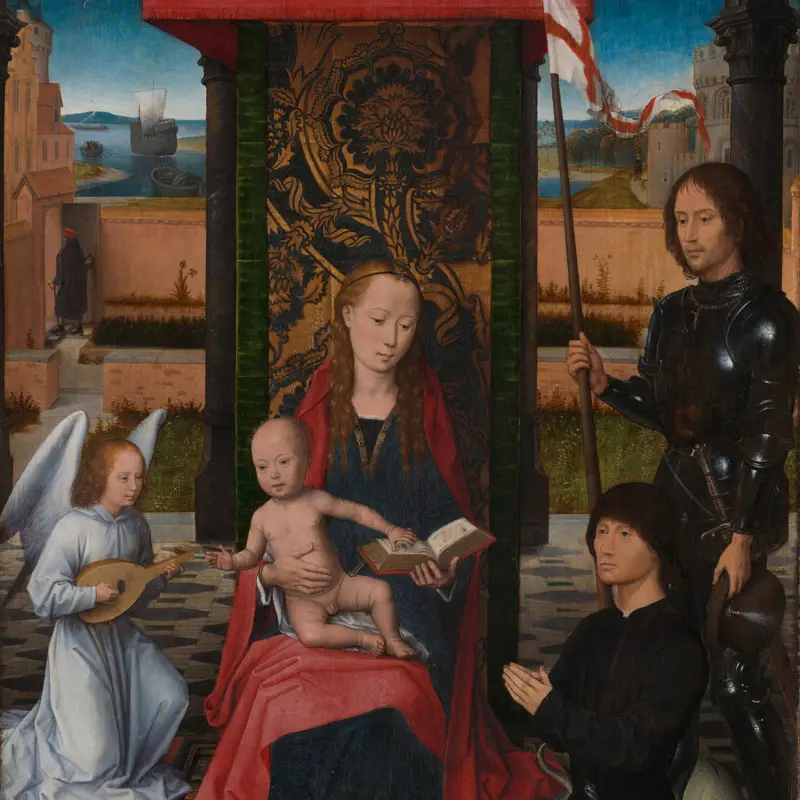

This is the central panel of a small triptych (a painting in three parts), probably commissioned by Sir John Donne in the late 1470s. In it, he kneels before the Virgin and Christ Child, facing his wife Elizabeth and one of their daughters. They are accompanied by their patron saints Catherine and Barbara, and Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist appear on the side panels (also in the National Gallery’s collection).

Sir John’s nose was enlarged during the course of painting, and rapid, hatched brushstrokes indicate shadows and stubble. His head seems to have been painted rapidly and from life. Lady Donne initially looked very like the youthful Saint Barbara but she was made – presumably – more realistic in the course of painting, with thinner lips and a sharper nose. It seems that Memling first painted an idealised head and changed it either when he met Lady Donne or was supplied with better information by her husband.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Virgin and Child with Saints and Donors (The Donne Triptych)

- Artist

- Hans Memling

- Artist dates

- Active 1465, died 1494

- Part of the group

- The Donne Triptych

- Date made

- About 1478

- Medium and support

- Oil on wood (probably oak)

- Dimensions

- 71 × 70.3 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Acquired under the terms of the Finance Act from the Duke of Devonshire's Collection, 1957

- Inventory number

- NG6275.1

- Location

- Room 53

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 20th-century Replica Frame

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Lorne Campbell, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools’, London 1998; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2017Monochrome: Painting in Black and WhiteThe National Gallery (London)30 October 2017 - 18 February 2018

Bibliography

-

1761London and Its Environs Described: Containing an Account of Whatever is Most Remarkable for Grandeur, Elegance, Curiosity or Use, in the City and in the Country Twenty Miles around it, 6 vols, London 1761

-

1837G.F. Waagen, Kunstwerke und Künstler in England und Paris, vol. 1, Berlin 1837

-

1840J.G. Nichols, 'Picture at Chiswick, attributed to van Eyck', Gentleman's Magazine, XIV, 1840, pp. 489-91

-

1937A.J. Finberg, 'Vertue Note Books, V', The Walpole Society, XXVI, 1938

-

1958The National Gallery, The National Gallery: July 1956 - June 1958, London 1958

-

1967M.J. Friedländer, Early Netherlandish Painting, eds N. Veronée-Verhaegen and H. Pauwels, trans. H. Norden, 14 vols, Leiden 1967

-

1970M. Davies, The National Gallery, London, Les Primitifs flamands. I, Corpus de la peinture des anciens Pay-Bas méridionaux au quinzième siècle 11, Brussels 1970

-

1971K.B. McFarlane, Hans Memling, Oxford 1971

-

1980W. Jahn, 'Der Maler Hans Memling aus Seligenstadt: Burger zu Pruck in Flandern gewest', Archiv für hessische Geschichte und Altertumskunde, XXXVIII, 1980, pp. 45-94

-

1981D. Sutton, 'Aspects of British Collecting, I: Early Patrons and Collectors', Apollo, CXIV/237, 1981, pp. 282-97

-

1983J. Mills, Carpets in Paintings (exh. cat. The National Gallery, 1 June - 24 July 1983), London 1983

-

1986M. Scott, A Visual History of Costume: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, London 1986

-

1987Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Early Netherlandish School, 3rd edn, London 1987

-

1991J. Dunkerton et al., Giotto to Dürer: Early Renaissance Painting in the National Gallery, New Haven 1991

-

1994P. Lorentz and N. Reynaud, 'Un "ange" de Hans Memling (v. 1435-1494)', Revue du Louvre, XLIV/2, 1994, pp. 10-7

-

1995L. Gent (ed.), Albion's Classicism: The Visual Arts in Britain, 1550-1660, New Haven 1995

-

1996C. Stroo et al., The Flemish Primitives: Catalogue of Early Netherlandish Painting in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, 6 vols, Brussels 1996

-

1997J.V. Field and F.A.J.L. James, Science in Art: Works in the National Gallery That Illustrate the History of Science and Technology, Stanford in the Vale 1997

-

1997R. Billinge et al., 'Methods and Materials of Northern European Painting in the National Gallery, 1400-1550', National Gallery Technical Bulletin, XVIII, 1997, pp. 6-52

-

1997L. Campbell, 'The Donne Triptych', in H. Verougstraete-Marcq, R. van Schoute and M. Smeyers (eds), Memling Studies: Proceedings of the International Colloquium. 10-12 November, Bruges, 1994, Louvain 1997, pp. 243-4

-

1998Campbell, Lorne, National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings, London 1998

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

-

2002M. Belozerskaya, Rethinking the Renaissance: Burgundian Art across Europe, Cambridge 2002

-

2002F. Koreny, Early Netherlandish Drawings: From Jan van Eyck to Hieronymus Bosch (exh. cat. Rubneshuis, 14 June - 18 August 2002), Antwerp 2002

-

2003R. Marks and P. Williamson, Gothic: Art for England 1400-1547, (exh. cat. Victoria and Albert Museum, 9 October 2003 - 18 January 2004), London 2003

-

2004J.O. Hand, Joos Van Cleve: The Complete Paintings, New Haven 2004

-

2005T.-H. Borchert et al., Memling's Portraits (exh. cat.), Amsterdam 2005

-

2008L. Monnas, Merchants, Princes and Painters. Silk Fabrics in Italian and Northern Paintings, 1300–1550, New Haven 2008

-

2008B.W. Meijer (ed.), Firenze e gli antichi Paesi Bassi, 1430-1530: Dialoghi tra artisti da Jan van Eyck a Ghirlandaio, da Memling a Raffaello (exh. cat. Palazzo Pitti, 20 June - 26 October 2008), Livorno 2008

-

2009B.G. Lane, Hans Memling: Master Painter in Fifteenth-Century Bruges, London 2009

Frame

This frame – part of a triptych – was made in Brussels in 1958 by Le Cadre S.A. It is crafted from pinewood, with polychrome and painted marbling. Following the tradition of Flemish frames, the triptych incorporates a black fillet, a marbled frieze with mitre pegs and a sill. The sight moulding is water-gilt.

The side wings are double-sided frames. On the reverse of these wings is a marbled frieze with a stone-coloured cavetto moulding at the sight edge. The reverse of the central panel is marbled.

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the group: The Donne Triptych

Overview

Courtier and soldier Sir John Donne kneels before the Virgin and Christ Child in the central panel of this triptych (a painting in three parts), which he commissioned, facing his wife Elizabeth and one of their daughters. With them are Saints Catherine and Barbara, two of the most popular medieval saints; the wings show Donne’s patron saints, John the Baptist and John the Evangelist. On the outside of the wings Saints Christopher and Anthony Abbot are shown as stone statues in niches.

The younger son of a Welsh soldier, Donne was a career administrator who owed his fortune to King Edward IV. He and his wife wear the King’s livery collars. The composition is a version of Memling’s famous Triptych of the Two Saints John (Memling Museum, Bruges), which he worked on in the late 1470s. Perhaps Donne saw it in Memling’s workshop and asked for something similar.