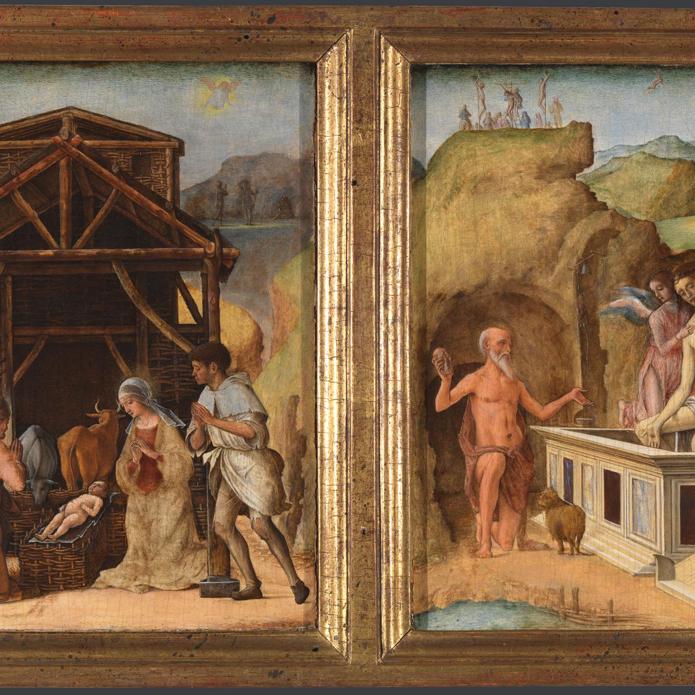

Ercole de' Roberti, 'The Adoration of the Shepherds', about 1490

About the work

Overview

This small panel is painted in fine detail, resembling a precious painted miniature or illuminated manuscript. It formed the left side of a diptych (a work of two parts) joined with a central hinge; the other side showed The Dead Christ. Joseph, the Virgin Mary and a shepherd in torn clothes pray before the infant Christ. He lies naked in a manger in front of an elaborate wooden structure that looks more like a temple or church than a stable. Although it is made of humble materials, its design reflects the ideas of the eminent local architect, Alberti, whose church architecture incorporated features of ancient Roman architecture. This cultural reference would not have been lost upon the diptych’s owner Eleonora of Aragon, Duchess of Ferrara. Eleonora focused her prayer upon the body of Christ and its place in the Mass, when Catholics believed that the bread and wine of the Eucharist became Christ’s body and blood. The focus here upon Christ’s naked body was appropriate for her private prayer.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Adoration of the Shepherds

- Artist

- Ercole de' Roberti

- Artist dates

- Active 1479, died 1496

- Part of the group

- The Este Diptych

- Date made

- About 1490

- Medium and support

- Egg tempera on wood

- Dimensions

- 17.8 × 13.5 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1894

- Inventory number

- NG1411.1

- Location

- Room 51

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Previous owners

- Frame

- 15th-century Italian Frame

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Martin Davies, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools’, London 1986; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2014Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance PaintingThe National Gallery (London)30 April 2014 - 21 September 2014

-

2023Ercole de' Roberti e Lorenzo CostaPalazzo dei Diamanti18 February 2023 - 19 June 2023

Bibliography

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.

Images

About the group: The Este Diptych

Overview

The Adoration of the Shepherds and The Dead Christ were originally joined with hinges to form a diptych – an object made up of two painted panels – that could open and close, creating a visual prayer book. It probably belonged to Eleonora of Aragon, Duchess of Ferrara. An inventory of her possessions records just such a work, covered in cherry-red velvet; traces of red velvet remain on the back of these two pictures. The images portray the beginning and end of Christ’s life but the focus is on his body.

Eleonora was particularly devoted to the Corpus Christi (‘the body of Christ’). She played a prominent role in the annual feast that celebrated the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper, when Christ instructed his disciples to drink wine and eat bread in commemoration of his blood and body. She was closely connected to a religious group that focused their prayer upon the Corpus Christi and was buried in their church in Ferrara.