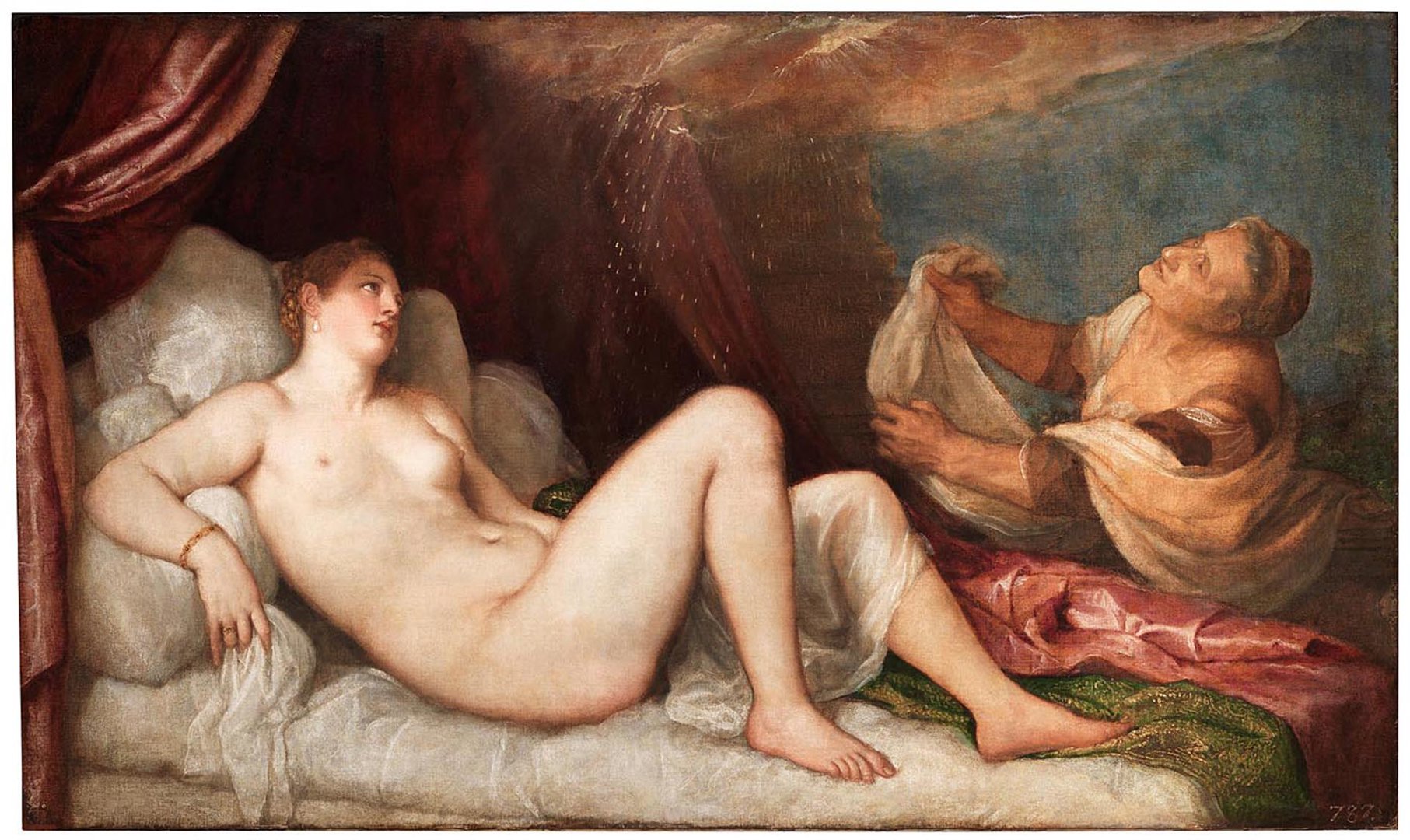

Danaë

One of the first of the cycle of paintings, Danaë tells the story of the daughter of King Acrisius of Argos. She was shut up in a tower by her father as a means of preventing her from ever having a son.

The heirless king had been told by the oracle (fortune teller) that he would have a successor and that this child would be his daughter's son. Good news only in part as he was also told that this grandson would kill him.

Meanwhile Jupiter, an admirer of Danaë and immune to any barrier, reaches her via a skylight in the form of a shower of gold. She goes on to have their child, Perseus, the hero of another of the 'poesie'.

Venus and Adonis

Titian paints Venus, filled with foreboding, clutching for her lover, the beautiful hunter Adonis, in an attempt to stop him from going hunting. However, his fate is sealed. He does not return; gored to death by a wild boar.

Diana and Actaeon

Diana, chaste goddess of hunting is disturbed, while bathing accompanied by nymphs, by the hunter Actaeon. He recoils. His arms raised almost as if to protect himself.

The telling reaction on the nymphs' faces and Diana's dreadful glare indicate that he has - unwittingly - infuriated her. The consequence is fatal. Titian hints at Actaeon's punishment by including a stag being chased by Diana on the skyline. Diana transforms Actaeon into a stag which is savaged by his own hounds.

Diana and Callisto

Here again, Titian retells in paint the story of someone incurring the wrath of Diana. The distraught nymph and hunting companion, Callisto, implores Diana as she is roughly stripped to reveal her pregnancy.

Callisto’s vow not to marry and her subsequent rape by Jupiter (who changed her into a bear) have tipped Diana over the edge. Diana goes on to kill Callisto, not realising that she has taken animal form.

Jupiter immortalises Callisto by transforming her into the constellation Ursa Major (the Great Bear).

Perseus and Andromeda

Andromeda was the beautiful daughter of King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia. Cassiopeia offended the Nereids, the sea nymphs, by claiming that Andromeda was more beautiful than they.

In revenge, Neptune, god of the sea, sent a sea monster to devastate Cepheus’s kingdom. Andromeda is chained to the rocks to be devoured by the monster when the hero Perseus flies by and falls in love with her.

Perseus then swoops down to rescue her, his powerful vertiginous descent contrasting vividly with her passive vulnerability. He slays the monster and later marries Andromeda.

Rape of Europa

Jupiter, captivated by Europa, transforms himself into a beautiful bull and joins the herd of cows around her.

Europa approaches the bull and, finding it tame, winds flowers around its horns and jumps onto its back. The bull (aka Jupiter) leaps into the sea and carries her off. Europa clings on in terror, a flailing arm waving desperately at her companions on the beach.