The Virgin of the Rocks is a complex and mysterious painting which has intrigued people for centuries.

For an artist who notoriously left works unfinished and from whom even fewer survive, this is a rare example of one of his large-scale paintings.

It gives us insight into some of Leonardo’s ground-breaking scientific observations, demonstrating techniques and innovations which transformed Italian painting.

Leonardo began his painting career in Florence, but in the early 1480s he moved to Milan in search of new opportunities. Shortly after his arrival in the city he received the commission to paint ‘The Virgin of the Rocks’.

The painting was to be part of a grand altarpiece which included a wooden statue of the Virgin Mary. The altarpiece was destined for the chapel of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary in the church of San Francesco Grande, the principal church of the Franciscan Order in Milan and the largest church in the city after the Cathedral.

The painting was commissioned in 1483, but wasn't completed to the Confraternity’s satisfaction until 1508, twenty-five years later. A dispute over money led Leonardo to sell his first version of the picture (image above) – which is now in the Louvre, Paris. The confraternity finally managed to come to an agreement with Leonardo, and he began work on a second version of the painting; the one that is now in our collection.

The Immaculate Conception

The idea of Mary’s Immaculate Conception was much debated in Medieval Europe – the Franciscan order supported it, while the Dominicans contested it. Supporters of the Immaculate Conception argued that in order for Christ to be born without original sin (which originated at the moment Adam and Eve disobeyed God in the Garden of Eden), his mother, Mary, also had to be free of sin. It was therefore necessary for the Virgin to have been conceived by God even before the creation of the world – and so before original sin.

In 1476 (less than a decade before ‘The Virgin of the Rocks’ was commissioned), Pope Sixtus IV at last adopted the feast for the Western church. The subject was still so new there was no standard way of showing it, giving Leonardo free rein to create a new composition.

In his final version he painted the Virgin, the infant Saint John the Baptist (a gilded cross under his arm), and an angel, kneeling behind Christ – a chubby cross-legged child. The three figures communicate with each other through their hand gestures and directed gazes while the angel acts as a heavenly witness to the scene.

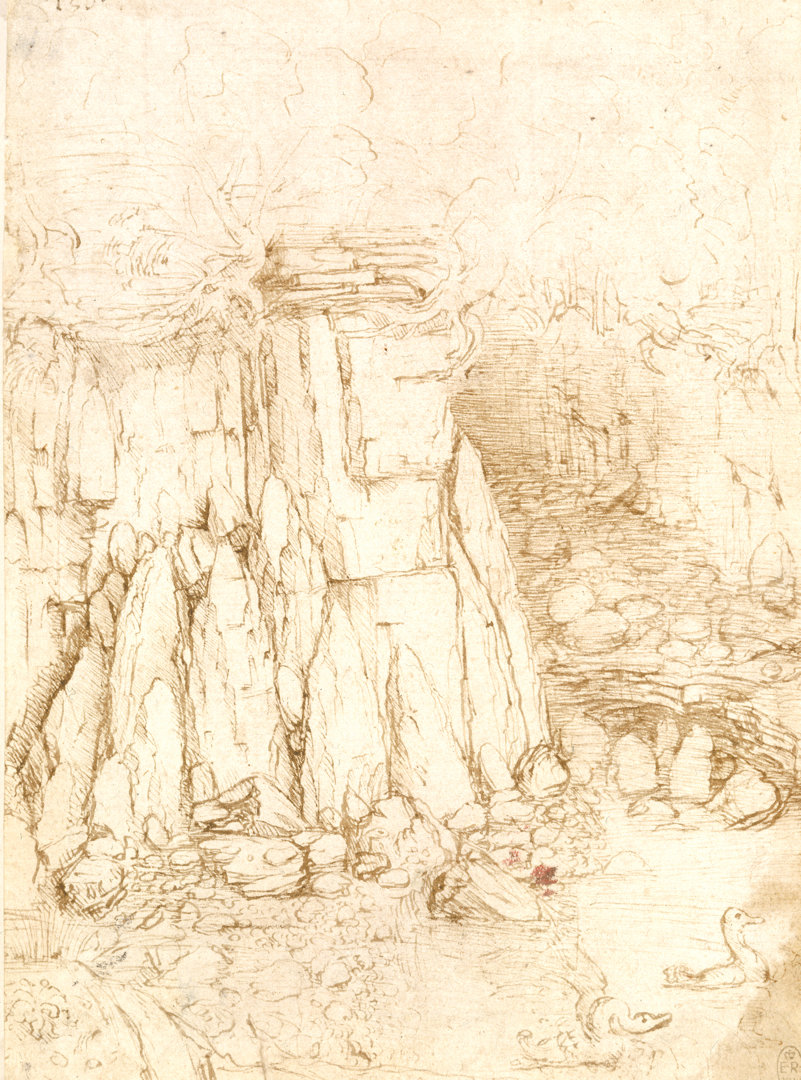

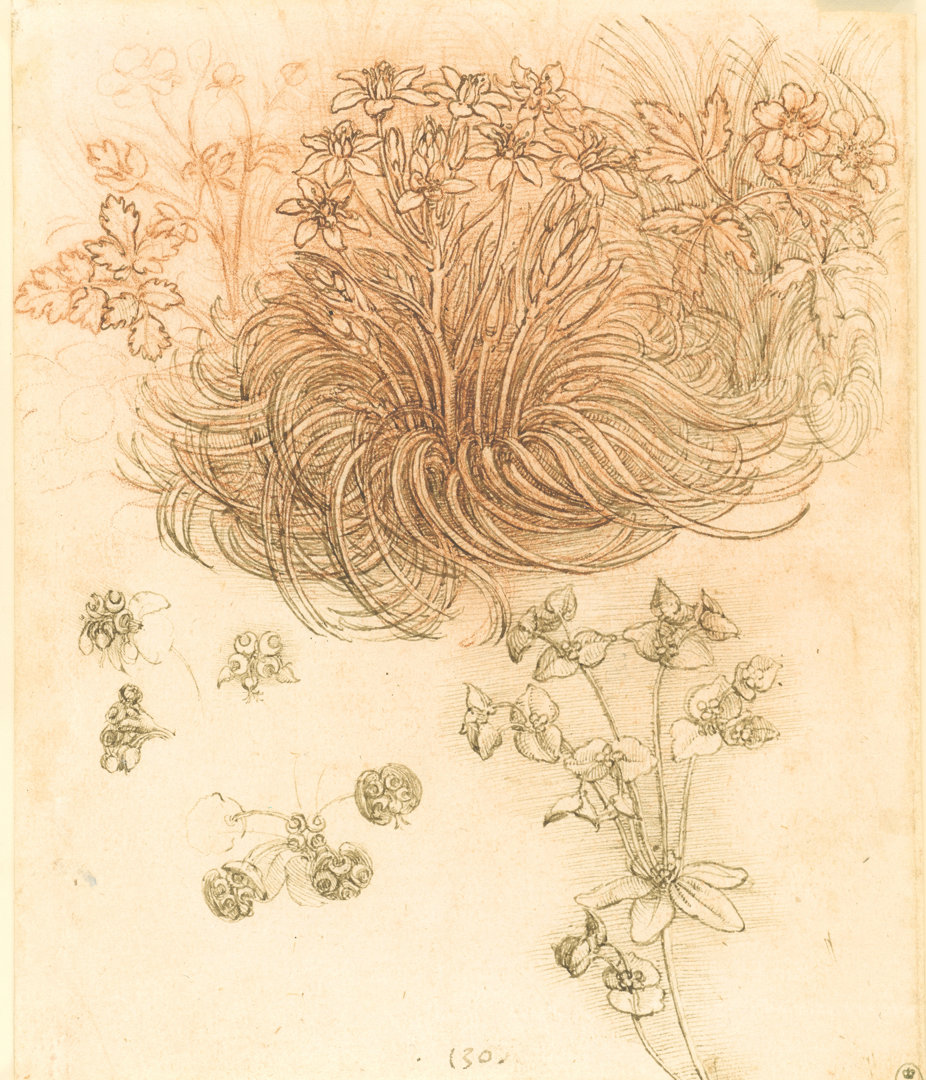

Leonardo had a lifelong fascination with the natural world. His surviving drawings include numerous observations of nature: swirling water, dramatic rock formations, trees and detailed plant studies. He studied the landscapes of the areas in which he lived in detail, and observed the effects of water and time on the natural environment.

This interest in the natural world is reflected in the attention he gives to the other-worldly landscape in ‘The Virgin of the Rocks’. The rocks structure the whole painting with the vertical thrust of their pinnacles, broken surfaces, and dark fissures. Their upward energy contrasts with the water’s flat stillness.

This wilderness is fertile: the plants beneath Saint John the Baptist and the Virgin are growing strongly with bright flowers and healthy foliage. Plants even sprout from the rocks above. But the flowers don’t resemble any real flowers – they are invented hybrids of different plants.

These apparently primeval elements suggest the scene may be set in the earliest moments of creation: the first verses of the biblical creation story tell of God creating the earth out of the watery deep.

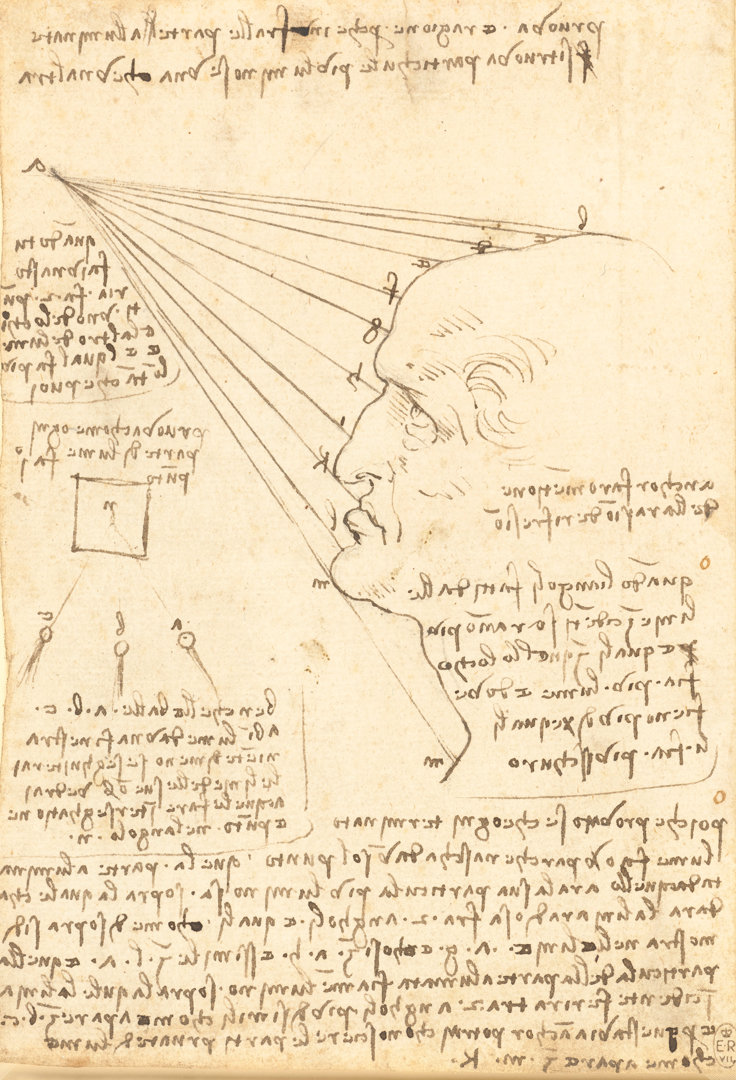

Leonardo gives the impression of the landscape’s vastness through a technique we now call ‘aerial perspective’. From his studies in optics, he realised that we perceive the same colours differently depending on their distance from us; mountains appear blue and paler if viewed from far off.

He softened their edges so they appear hazy, another technique that mimics the effects of vision in reality. The light towards the horizon and the cool blue of water and distant mountains also contrasts directly with the warm dark browns of the earth and rocks.

‘The Virgin of the Rocks’ demonstrates Leonardo’s revolutionary technique of contrasting light and shadow, known as ‘chiaroscuro’ to define three-dimensional figures.

By blocking out most of the sky and surrounding his figures with tall rocky outcrops, overhanging ledges, and dark hollows, Leonardo creates a gloomy environment from which the figures’ faces and bodies emerge as though spot-lit. This unnatural illumination emphasises their divine beauty. In some notes destined for the artist’s manual he was compiling, Leonardo remarked how even the faces of ordinary people look beautiful at dusk when the light is low.

Leonardo achieves subtle transitions between light and shadow through another innovative technique, now known as ‘sfumato’ – from the verb ‘turn to smoke’. By using this smoky, blurry effect around the edges of forms, such as around the Virgin’s temples and nose, rather than stark outline, the figures appear to emerge subtly from the darkness. It is the beautiful modelling of flesh and skin using fine gradations of smoky grey tones that makes each figure appear three-dimensional.