The shelter

The Luftwaffe flew intensive bombing sorties over London day and night throughout the autumn and winter of 1940-41. The city was under siege yet somehow the concerts continued.

Audiences picked their way through streets strewn with glass and rubble, skirting bomb craters and smouldering ruins, to find the National Gallery still standing and the performers at their posts.

Felix Kok, performer at the concerts

Transcript

Felix Kok: It was always organised it seemed to me rather at the last minute because after all you never knew whether the building was going to be there the next day, cause it was 1941 and the Blitz. Mind you we didn’t have bombing raids during daylight, but so much could have been destroyed the night before, and therefore it was always hanging on a very slender piece of string what was going to happen. I just think looking back it was so wonderful that this idea came about and it was pursued for so long.

I always remember Trafalgar Square also because South Africa House overlooks the Square, and so I used to have to go there for various reasons cause when I travelled I was on a South African passport. I had to get a visa so I was always finding myself there and you know you saw the scarred buildings, oh it was, one always wondered what on earth was it going to be like when it all ended, and how was it ever going to be repaired cause it was such a mess. It took years before anything started to change, but my goodness, when I see pictures of the National Gallery with the odd bus and the empty streets with no cars and the occasional taxi it brings it all back to me.

Such extraordinary circumstances inevitably brought challenges. Government buildings were expected to close their doors during air raids and admit no one, a policy that saw the start of concerts regularly delayed.

Audiences responded by queuing patiently outside the Gallery until the All Clear had sounded and performances could take place. Once inside the building, concert-goers found conditions considerably more cramped and less comfortable than in the days before the Blitz.

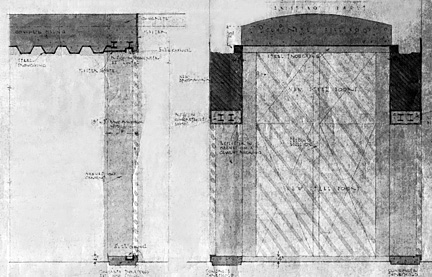

Performances had previously been held in a grand set of galleries beneath a glass dome. Now, the severity of the daytime bombing raids necessitated a move to a new home downstairs in the basement.

The shelter had room for only 300 to 400 people, and rapidly became inhospitable when the temperature either rose or fell. In the summer it was hot and airless. Audience members fainted and string players struggled to keep their instruments in tune.

In the winter piercing draughts from the blown-out windows made rugs and blankets a necessity for audience and musicians alike.

Large pools of water collected on the stone floor despite the tireless efforts of the Gallery attendants; Myra Hess played in a fur coat; and stoves were placed on the platform to stop the performers’ fingers turning blue.

On one particularly icy day a clarinettist was seen trying to heat her instrument over a stove in a vain attempt to get it up to pitch.