Re-opening Room 29: The Wolfson Gallery

First opened to the public in 1930, Room 29 is one of the largest spaces in the Gallery. Since its doors closed in March 2022, we have been busy making important changes to the room to bring it into the 21st century.

But what is the history of this room and what did it look like before? Find out as we go behind the scenes:

A new addition in the history of the Gallery

You might be surprised to learn that Room 29 didn’t exist when the Gallery first opened its doors on Trafalgar Square in 1838. It was built as part of a new extension in the 1920s to house the Gallery’s growing collection.

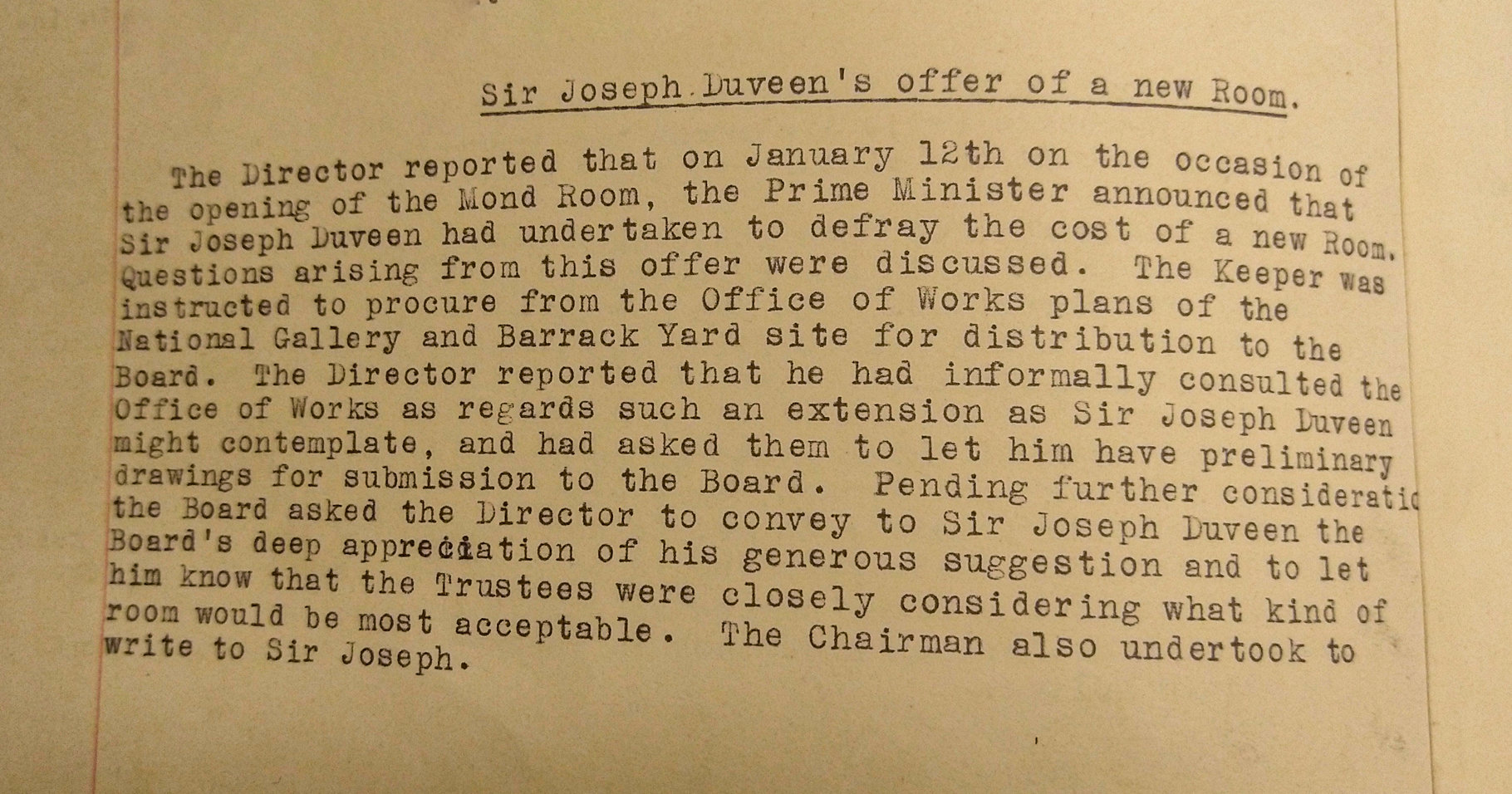

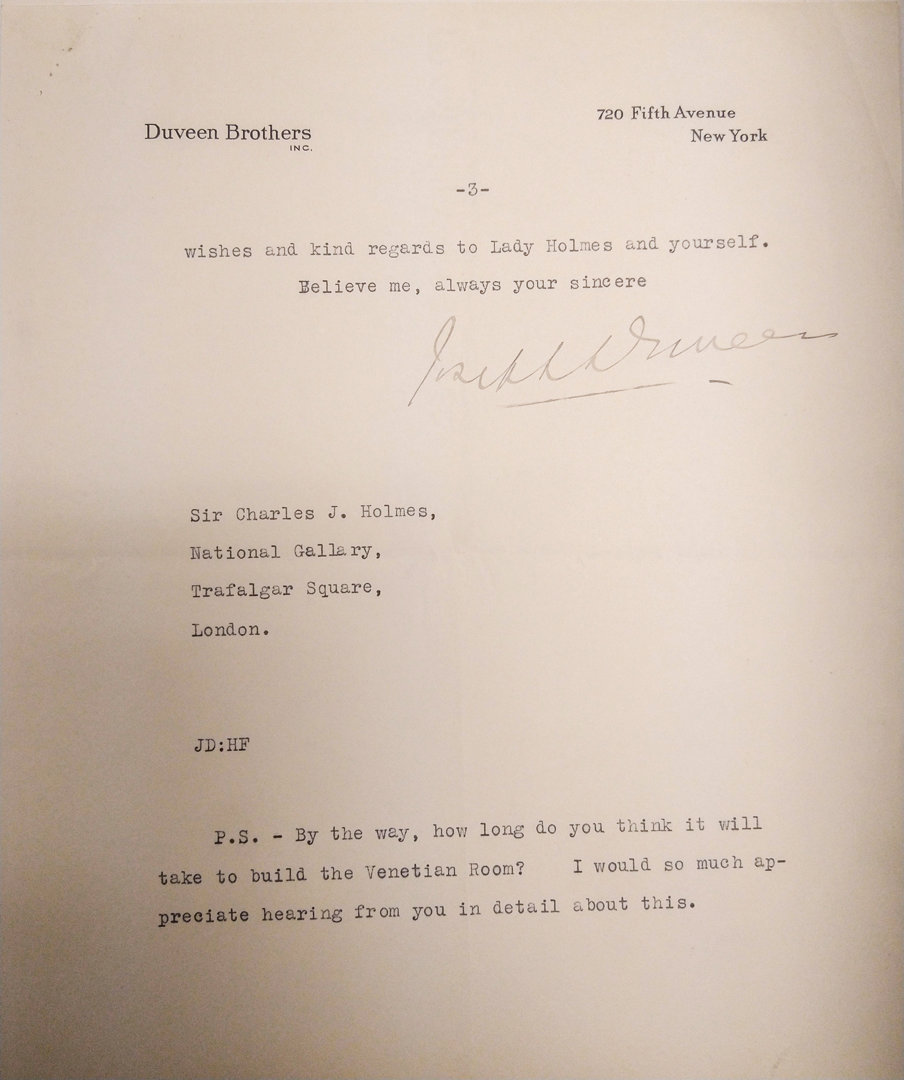

The project was funded by Joseph Duveen in 1928. His offer was sent first to the Prime Minister at the time, offering to pay for the cost of building a 'Venetian Room', and was followed up with a letter sent to Sir Charles Holmes, the Gallery’s Director.

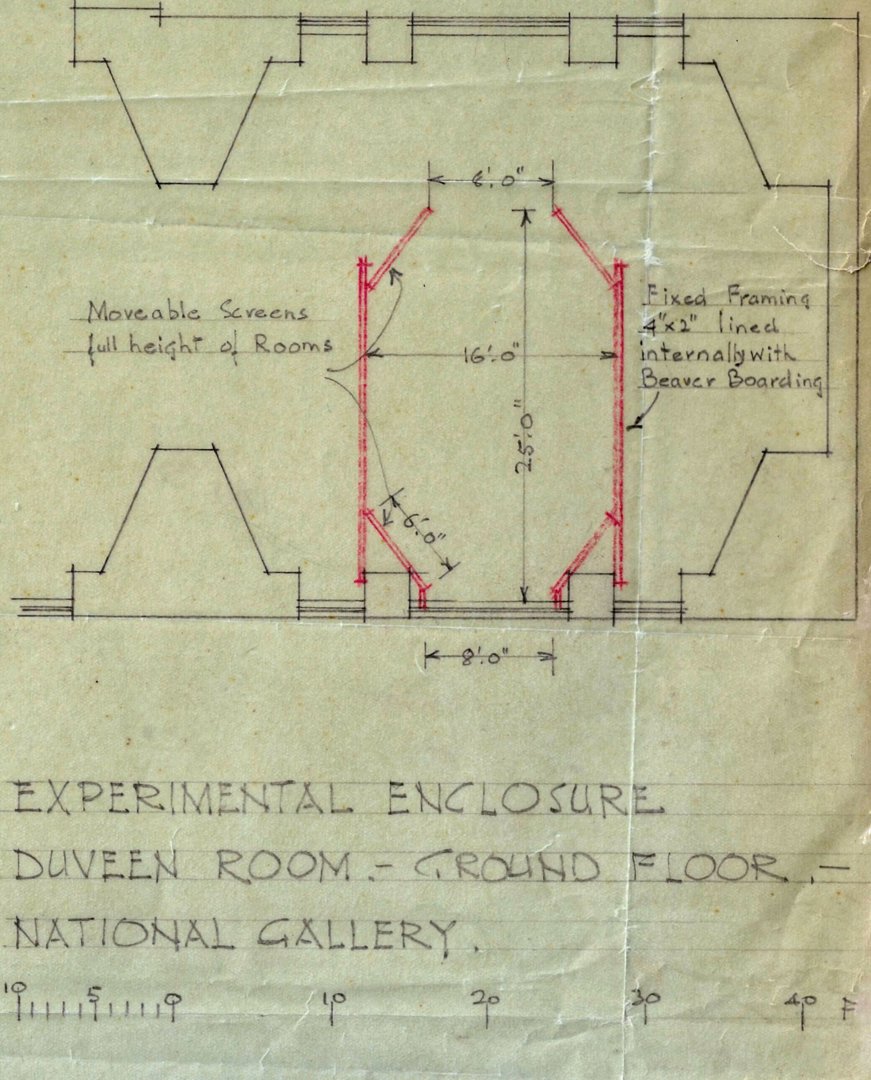

In 1929, during the planning process, the elected architect, Sir Richard Allison created a model of the room, complete with movable screens and frames for experimental hanging. Even a century ago, the room was intended to hang 'Venetian and North Italian pictures' just as it is today. The wall coverings were agreed to be light, the fabric to be grey and the moulding to be painted grey to match. This was inspired by the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid.

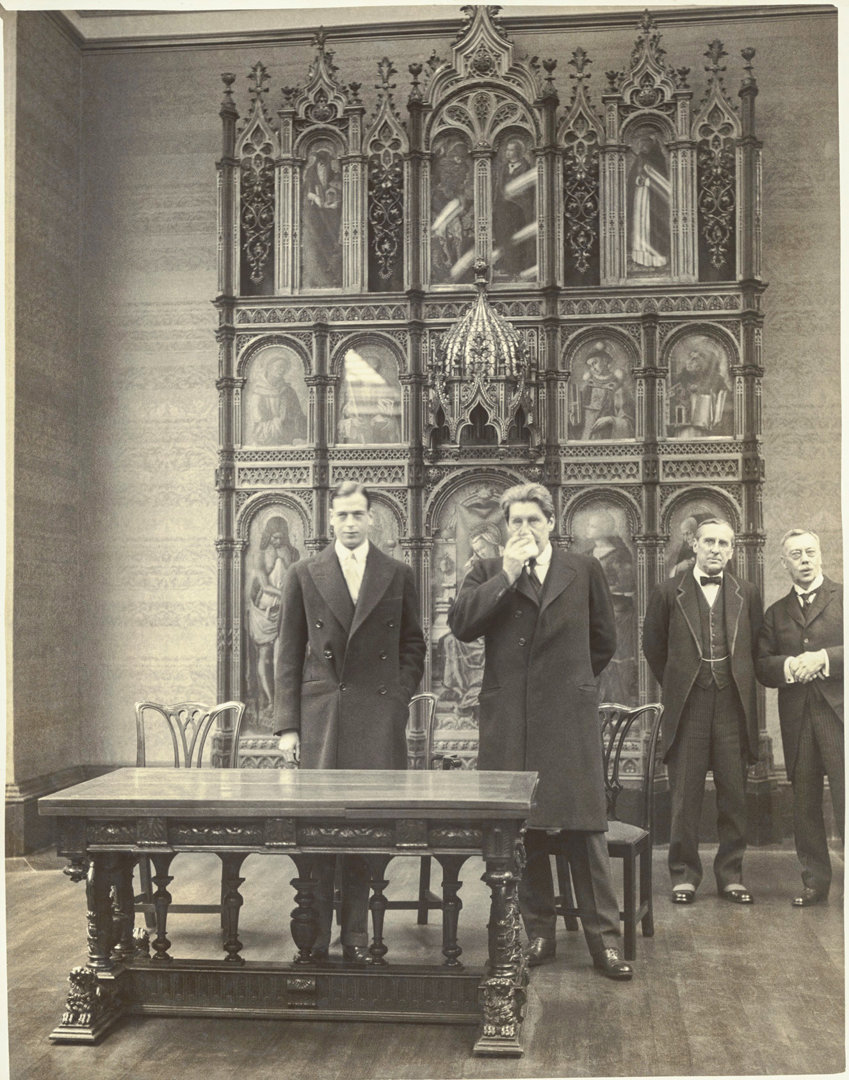

The room was opened by Prince George, Duke of Kent, in January 1930.

A room devastated by war

During the Second World War, the Gallery’s collection was sent for safe keeping to a disused slate mine in Manod, Wales.

The Gallery was bombed nine times between October 1940 and April 1941. Room 29 was one of the spaces that was badly damaged.

The room was repaired and reopened in 1950. It was redecorated with pale gold damask and our German and Flemish paintings graced its walls.

In the 1970s, architectural modifications were made, including the installation of air conditioning units. Temporary walls and false ceiling were also added, which created smaller rooms.

Sir Martin Davies, Director at the time, believed that 'the ideal of hanging – for the National Gallery – is that all the pictures look their best, and nobody notices anything but them'. This meant obscuring any architectural features and adjusting rooms to suit different types of paintings. The Gallery started to experiment more with the display of the pictures in the existing main floor rooms.

A new space, nearly 100 years on

You may not notice some of the changes we’ve made to the room, but these all help to enhance your enjoyment of our paintings. With new technologies, we’re able to better control the natural light that comes into the room, helping visitors to enjoy our paintings even more. The walls have changed to a warm olive green to complement the paintings, and the floors have been replaced with a light oak to make the room feel brighter.

During the refurbishment we’ve used 440 metres of fabric, 600 metres of braiding and over 800 linear metres of gilded mouldings.

This redisplay celebrates the major refurbishment of this room, made possible through the generous support of the Wolfson Foundation. Their support has enabled the realisation of this project, breathing life into the newly named Wolfson Gallery.