Yolande Lyne Stephens, née Duvernay

1812–1894

Antoine Watteau, La Gamme d’Amour (The Scale of Love) (NG 2897)

Yolande Marie Louise Duvernay was born at Versailles in December 1812. Her father was an actor, as had been her mother as a young woman. The family moved to Paris when Yolande was six, and she then studied dance for the next twelve years. Her first leading role, under the name Pauline Duvernay, was in Meyerbeer’s opera Robert le Diable performed at the Opéra de Paris in 1831.1 She was greatly admired both as a dancer and as a woman, one contemporary later describing her as ‘one of the most ravishing women you could wish to see; she was twenty years old, had charming eyes, an admirably turned leg, and a figure of perfect elegance’.2 In 1833 she performed at the Theatre Royal, London, where the young William Makepeace Thackeray described her as a ‘vision of loveliness’.3 She returned to London the following year and formed a relationship with Edward Ellice, the son of a Cabinet minister. However, she soon returned to Paris and to her previous lover, Louis Véron, director of the Opéra, who described her as a melancholic who frequently burst into tears.4 Abandoned by him, and then in 1835 by her subsequent lover, the marquis de La Valette, by whom she seems to have had a child, she made two suicide attempts at the end of that year.5 In 1836–7 she performed in London where she was paid £600 a month (the equivalent of some £50,000 today).6 In her celebrated role as Florinda in the ballet, Le Diable boiteux, she was the subject of a number of portrait prints.7

It was during her third and last London season in 1837 that Yolande met Stephens Lyne Stephens (1801–1860), whose father had inherited a substantial fortune from a cousin.8 Lyne Stephens was briefly an officer in the 10th Hussars, but saw no active service, and was even more briefly MP for Barnstaple.9 His preference, however, was for a life of leisure on the back of his father’s fortune.10 With the help of his friend, the comte d’Orsay, Lyne Stephens negotiated for Yolande’s favours: her mother received a one-off payment of £8,000, and she herself an allowance of £2,000 per annum for two years, convertible into a lifetime annuity from January 1840, on condition that she remained faithful during the two-year period. After a period of living together at Lyne Stephens’s father’s house in Portman Square, London, he and Yolande married on 14 July 1845, and honeymooned in France and Italy. Four years later they moved into Grove House, Roehampton (now part of the University of Roehampton), in Surrey. Lyne Stephens’s father died in 1851 leaving him an annual income of £3 million in today’s values, making him allegedly the richest commoner in England.11 In the years that followed he remodelled Grove House and had by early 1856 bought the hôtel Molé (formerly the hôtel de La Vaupalière) at 85 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Paris.12 He also started to have built a country mansion at Lynford Hall (sometimes called Lynsford Hall), Mundford, near Thetford in Norfolk, on an estate of nearly 8,000 acres.13

Stephens Lyne Stephens died in February 1860, with Lynford Hall incomplete. It would not be occupied until 1862. He bequeathed Grove House and his art collection to Yolande absolutely, and Lynford Hall to her for her life. She also inherited the Paris property for life.14 She became more pious, outwardly at least, commissioning from her late husband’s architect, William Burn, an elaborate mausoleum and sarcophagus which were placed in the grounds of Grove House in 1864,15 contributing to religious foundations in Paris and Roehampton, and from 1879 funding the construction of one of the largest Catholic churches in England, the Church of Our Lady and the English Martyrs in Cambridge.16 From the early 1860s her grief was tempered by a liaison with, and devotion to, Edward Claremont, the married British military attaché in Paris, who was a friend of the Marquess of Hertford and of his son, Richard Wallace.17 It was with Claremont’s advice, and possibly that of Wallace, that Yolande expanded her art collection. It was also on Claremont’s advice that in 1875 she sold the hôtel Molé and found an apartment on the Champs-Elysées.18 A partial account of the apartment is given in a letter of June 1882 from Claremont’s daughter-in-law to her mother: ‘The rooms are a dream, all opening out of each other, full of curios: china, pictures, and tapestry. My room is very pretty. The walls are covered with copper-coloured brocade and the furnishings are pale blue.’19

Edward Claremont died in 1890, and it was to his son, Harry, who had taken over the management of Yolande’s affairs from his father, that she bequeathed Grove House and her residuary estate in England. Harry died in 1894, a few months after Yolande’s death on 2 September 1894, having, as required by the will, changed his surname to ‘Lyne Stephens’.20 Yolande’s lawyer, Horace Pym, inherited her residuary estate in France, including the Champs-Elysées property.21 The French estate was the subject of a number of bequests, including one to the National Gallery of three paintings.22 By her English will of 8 March 1887, Yolande, then 75 years old, had bequeathed part of her art collection at Roehampton and Lynford to the nation, with her pictures going, as the Lyne Stephens Collection, to the National Gallery, and furniture and porcelain to the South Kensington Museum. On 12 June 1894, however, she revoked the bequests under the English will to both institutions, so that, save for the bequests made to them under her French will, Yolande’s collections fell into residue and were auctioned in 1895 and 1911.23 The apparent reason for the revocation, made a few weeks before her death, was that the Finance Bill of 1894 proposed an increase in the rate of death duties on large estates.24

Attached to the will of 8 March 1887 was an inventory of the same date including a list of the 45 paintings then intended for the National Gallery. That list is set out in the appendix to this entry. The inventory may originally have been in manuscript which might explain why some artists’ names have been wrongly spelt in the typed version which formed part of the will as admitted to probate: for example, Vandes Meulen, Wonvermans, Bettini (author’s italics). Both it and the inventory of furniture and porcelain were expressed to be translated from the French, which at least raises the possibility that the French original was written, or dictated, by Yolande herself. This possibility is made greater by some of the language used to describe individual items which goes beyond what was necessary merely to identify them: for example, ‘Very beautiful portrait’ (a Velázquez), ‘A superb painting full of beautiful inspiration and fine proportion from top to bottom’ (a Murillo) and ‘A charming picture very fine in all respects’ (a Wouwermans).

Of the 45 paintings in the inventory, 20 hung at Lynford Hall and the remainder at Grove House, Roehampton. Since some of the same inventory numbers appear twice – once for a picture at Lynford Hall and once for a picture at Grove House – it is clear that separate numbering was established for each house. This applies also to the inventoried porcelain and furniture. The most likely explanation for the sequence of numbering is not that it reflects the chronological order of a piece’s acquisition,25 but rather the topography of the collection in the house in question. It should also be borne in mind that the function of the 1887 inventories was not primarily to list all the objects in the Lyne Stephens collection,26 but to identify the paintings which Yolande then intended to leave to the National Gallery, and the furniture and porcelain which she then planned to give to the South Kensington Museum. In the case of both properties, there are many numbers missing in the inventories, and these presumably represent items (not necessarily paintings, furniture or porcelain) that Yolande did not plan to give to either institution.

The double portrait sold in 1808 and 1810 was attributed to Quinten Massys. Between 1824 and 1900, NG1689 was invariably attributed to Massys. In 1901 it was catalogued as by Gossart;14 in the 1913 catalogue the idea was put forward that it might be by two different hands, one German and one Netherlandish.15 Though this theory was dropped after 1921, the portrait remained ‘ascribed’ to Gossart until 1945, when it was once more catalogued as by Gossart. The attribution has been accepted by Friedländer, who considered it ‘in many respects his masterpiece’,16 by Davies and by most other art historians.

Date

Weisz dated the portrait in the 1500s, von der Osten towards 1513; Pauwels, Hoetink and Herzog placed it in the 1520s; Ainsworth between c.1515 and 1530.17 The dress of the couple may indicate that it was painted in the 1510s18 but, because they were old, they may not have kept up assiduously with current fashions. The style is close to that of the signed diptych of Jean Carondelet, dated 1517 (Louvre),19 and the Brussels donor portraits of about 1520; the attention to detail is less startling in the later portraits. The nudes in the man's hat-badge, whose poses derive from engravings by Dürer, are reminiscent of Gossart's ‘Neptune and Amphitrite’ (Berlin), dated 1516.20

Such half-length double portraits were known in the Low Countries in the fifteenth century and appear to have been relatively common in Germany.21 Two portraits by Quinten Massys, which may be cut from one double portrait, were painted at about the same time as NG1689 and show sitters who are similarly failing to communicate with each other.22 According to Smith, Gossart has brought the couple ‘the more together to show them the more apart. Eyes averted, ignoring each other, they choose not to communicate. Thickly clothed as if to defend their bodies one from the other, they make a pitiful contrast to the young lovers in the cameo on the man's hat. They, like an emblem of honest communication, “eye-beames twisted”, stare into each other's eyes, baring their souls as they have bared their bodies. Held by the girl, a horn of plenty promises unashamedly physical joys. The elderly couple, haggard and sour, seem, through their incompatibility, never to have experienced such happiness ...’23

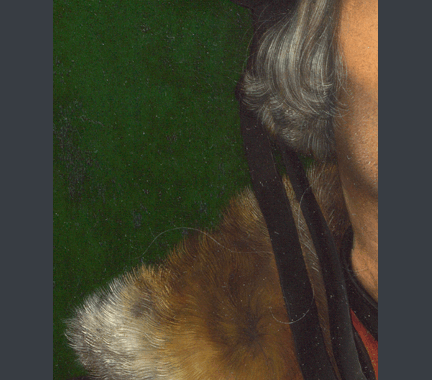

Although the woman is behind the man and although, in reality, her head was probably smaller than his, in the portrait her face is only very slightly smaller. Because it is more strongly lit, because it is surrounded by a large area of white veiling and because it is more centrally placed on the horizontal axis of the composition (whereas the man's head is just contained within the top half), she occupies the dominating position. She appears to be the younger and stronger of the two. She has retained most of her teeth, whereas he has lost his; the whites of her eyes are greyish but his are pink; she is tidily dressed but he is casting white hairs onto his collar. Her hands are concealed but his are clenched, perhaps rather desperately, around his fur collar and his staff – contrasted with the staff casually held by the young god in the hat-badge. She makes a bolder pattern of simple shapes, while his contours, as well as his body, are crumpled. He is shrinking – literally, for his body is much too small in proportion to his head. Though the two may not be communicating, she appears to buttress his decaying and shrivelled form.

View enlargement in Image Viewer

The parchment support is unusual and may suggest that the portrait was meant to be easily transported.24 That could imply that it was painted not for the sitters themselves but rather for some distant friend or descendant. The two heads are rather differently treated. The woman's is carefully outlined in the underdrawing and there are very few alterations, though the detail, for example in the hairs on her upper lip, is equally exacting; whereas the man's head is more sketchily underdrawn and there are many more changes. He may have been painted after the woman. They may never have seen the finished painting, may never have been aware of Gossart’s merciless observation of their physical decrepitude or the pitiful contrast between the young gods on the hat-badge and the collapsing flesh of their own bodies. The white hairs which have fallen from the man's head and which curl over his collar are not just triumphs of illusionistic virtuosity but a dreadful commentary on mortality (see fig.21 above, and photomicrographs m14 and m16 in Image Viewer).

Further Sections

- Introduction

- Provenance

- Exhibitions and version

- Technical notes

- Description

- The identities of the sitters

- Attribution and date

15. NG 1913 catalogue, p. 414.

16. Friedländer, vol. VIII, p. 39 and no. 80

17. Weisz 1913, pp. 78-9; von der Osten 1961, pp. 459–60; Pauwels, Hoetink and Herzog in the exh. cat. Rotterdam-Bruges 1965, p. 176; Ainsworth in Ainsworth et al. 2010, pp. 276–8.

18. See above.

19. Ibid., no. 4.

20. Ibid., no. 47. The poses derive from Dürer's ‘Temptation of the Idler’ (B.76) and his ‘Adam and Eve’ of 1504 (B.1).

21. Campbell 1990, p. 54 and references.

22. Private collection, Belgium, and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: ibid., pp. 34–7.

23. Smith 1973, p. 32.

24. Gossart's ‘Deësis’ (Prado), sometimes said to be on parchment, is in fact on paper, this time laid down on panel (Friedländer, vol. VIII, no. 19; exh. cat. Madrid 2006, pp. 102–13).