Italian, Florentine, 'Cassone with a Tournament Scene', probably about 1455-65

About the work

Overview

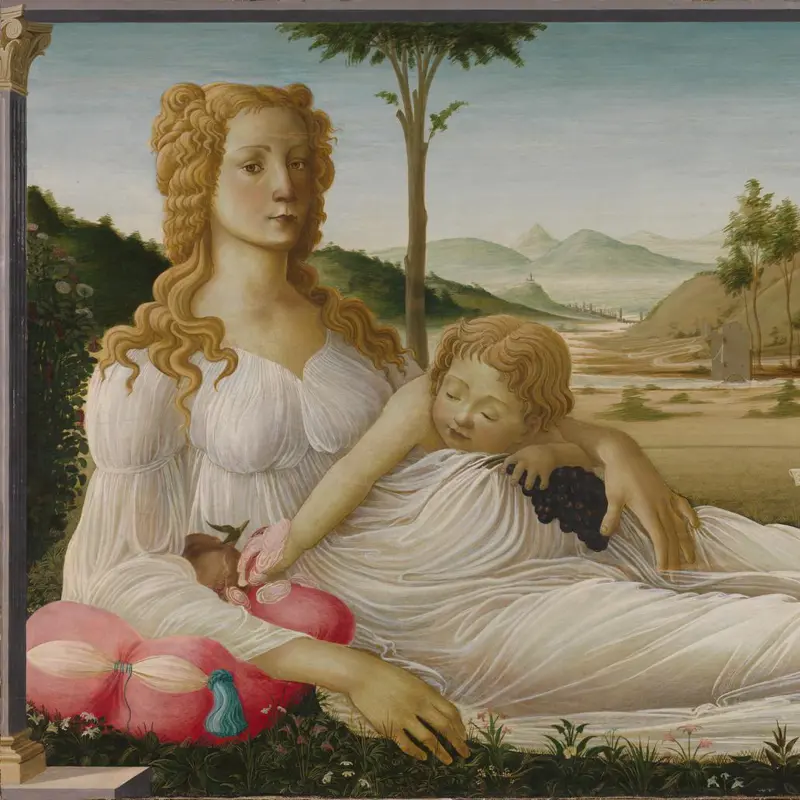

Painted chests like this are called cassone (literally ‘a large chest’). They were made to celebrate a marriage and were often used to store a new bride’s dresses and linens. Cassone were in such high demand in Florence that painters like Apollonio di Giovanni had workshops specialising in their decoration.

They were usually placed in the camera, a room with beds that was also a social space. Such a setting invited fashionable subjects, including poetry, ancient history and contemporary civic events, valued by the educated elite who could afford such items. This one shows a jousting tournament: two rows of opposing jousters, separated by wooden arches, aim to push each other off their horses with lances. The rich and busy setting allowed the painter to include lots of detail in the costumes as well as gold leaf in the horses' harnesses.

This chest was substantially altered and restored in the nineteenth century to transform it into a more elaborate structure.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- Cassone with a Tournament Scene

- Artist

- Italian, Florentine

- Date made

- Probably about 1455-65

- Medium and support

- Egg tempera on carved and gilded wood

- Dimensions

- 38.1 × 130.2 cm

- Acquisition credit

- Bequeathed by Sir Henry Bernhard Samuelson, Bt, in memory of his father, 1937

- Inventory number

- NG4906

- Location

- Not on display

- Collection

- Main Collection

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Martin Davies, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools’, London 1986; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Bibliography

-

1938National Gallery, National Gallery and Tate Gallery Directors' Reports, 1937, London 1938

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.