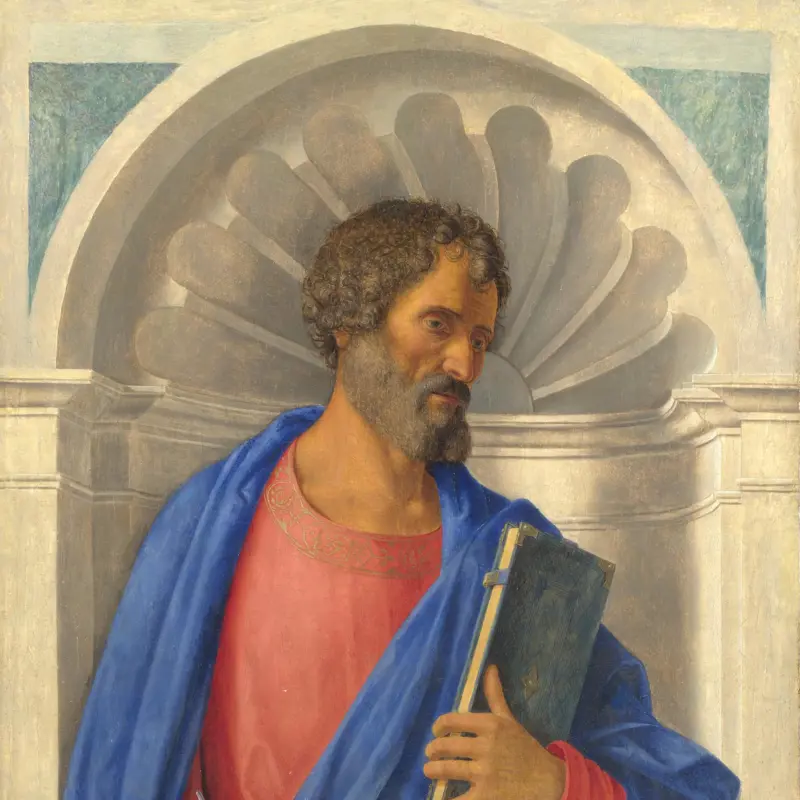

Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano, 'The Virgin and Child', probably about 1496-9

About the work

Overview

The Virgin sits in front of an Italianate landscape, the Christ Child standing on her lap. He twists his body to gaze lovingly at his mother, while her hand cups his left foot.

This picture, with its brilliant blues and greens, is among Cima da Conegliano’s finest works. It is one of several versions of the composition painted by him and his workshop. This one is thought to be mainly by Cima: the clear light and the contrasting colours are very characteristic of his style.

As well as being highly decorative, the composition has a strong underlying geometric structure. The Virgin and Child together form a wide-based triangle, their heads meeting at the apex. Christ’s body makes a narrower triangle, and the shapes of the hills, towns and mountains all echo these forms.

Key facts

Details

- Full title

- The Virgin and Child

- Artist dates

- About 1459/60 - about 1517/18

- Date made

- Probably about 1496-9

- Medium and support

- Oil on wood

- Dimensions

- 69.2 × 57.2 cm

- Inscription summary

- Signed

- Acquisition credit

- Bought, 1858

- Inventory number

- NG300

- Location

- Not on display

- Collection

- Main Collection

- Frame

- 16th-century Italian Frame

Provenance

Additional information

Text extracted from the ‘Provenance’ section of the catalogue entry in Martin Davies, ‘National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools’, London 1986; for further information, see the full catalogue entry.

Exhibition history

-

2010Cima da Conegliano: Poeta del paesaggioGalleria Comunale d'Arte Conegliano26 February 2010 - 2 June 2010

Bibliography

-

1951Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, London 1951

-

1986Davies, Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Earlier Italian Schools, revised edn, London 1986

-

2001

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, London 2001

About this record

If you know more about this work or have spotted an error, please contact us. Please note that exhibition histories are listed from 2009 onwards. Bibliographies may not be complete; more comprehensive information is available in the National Gallery Library.