Angelo Caroselli, 1585–1652

‘The Plague at Ashdod (after Poussin)’, 1631

Oil on canvas, 129 x 204.5 cm

NG165

Caroselli's painting is an almost exact, and exactly contemporary, copy after Nicolas Poussin's ‘The Plague at Ashdod’ of about 1631 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Although the painting can be documented almost to the moment of its creation, we still do not know why such a faithful replica was commissioned by the same collector who owned the original, possibly even before the original was completed.

Art collector and jewel thief

The Sicilian nobleman Fabrizio Valguarnera acquired Poussin’s original painting of ‘The Plague at Ashdod’ in Rome during February or March 1631. It was one of several paintings purchased with the spoils of a fabulous jewel heist. In August 1631, during a well publicised trial investigating the theft, Valguarnera testified that he had seen the painting in Poussin’s studio while it was still unfinished.

© RMN, Paris / All rights reserved

Valguarnera also commissioned Angelo Caroselli, a Roman painter, copyist and restorer, to make a copy of Poussin’s painting. Both original and copy were in Valguarnera’s possession by July 1631. It seems odd that Valguarnera would have owned both original and copy of ‘The Plague at Ashdod’, but he apparently owned other such ‘pairs’, and may have anticipated selling one or the other.

Copy or original?

The National Gallery’s version was listed as a copy in 17th-century inventories, but by 1714 it was described as ‘originale di Niccolò Pusino’, and it was as an original by Poussin that it was presented to the Gallery in 1838. Although it was recognised as a copy by the early 20th century, it was not until the 1990s that the painting was once again connected with the copy made by Caroselli at Valguarnera’s request.

How was it made?

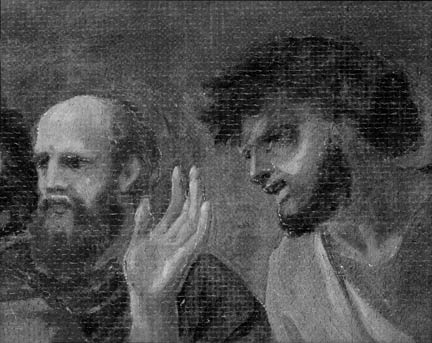

Caroselli was a respected copyist in his day: the 17th-century artists’ biographer Filippo Baldinucci reported that Poussin was himself deceived by a copy that Caroselli had painted. Caroselli seems to have worked directly from Poussin’s original when creating this copy. Tracing lines in lead white, visible at the outlines of several of the principal figures in the foreground, suggest that he had direct knowledge of Poussin’s original.

The lines were probably achieved by drawing the outlines of the figures on a sheet of fine translucent material placed over the original painting, then coating the back of the material with lead white. The material would then have been laid on top of a canvas prepared with a dark ground, and the outlines retraced to transfer markings to the new canvas.

Detecting differences

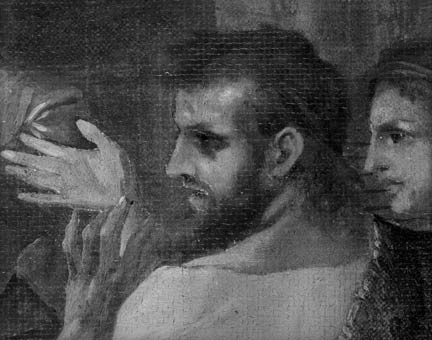

While the figures are repeated exactly from original to copy, the architectural settings are quite different. Infrared examination of the Louvre painting has shown that Poussin made changes to the background structures as he worked.

It has been proposed that the National Gallery’s picture was painted in Poussin’s studio while the original was still unfinished, and that the differences document Poussin’s earlier plan for the background of the Louvre picture. However, the architecture in Caroselli’s version does not correspond to the preliminary designs in the Louvre painting. Perhaps the differences represent Caroselli’s attempt to personalise his copy of Poussin’s original.

Materials and techniques

The materials and techniques Caroselli employed are fairly common for 17th-century Italian paintings, with the exception of an opaque bright yellow used in the drapery of the figure wearing a striped toga. X-ray diffraction analysis identified this as a lead-tin-antimony yellow, a relatively rare pigment most often found in paintings produced in Rome during the 17th century.

Over time, increased transparency of the oil paint, colour change of unstable pigments and greater prominence of the dark ground have altered the balance of colours in Caroselli’s painting. Smalt, for example (a blue pigment made from powdered glass coloured with cobalt oxide), was used in a mixture with green earth in the foliage and landscape. Over the centuries the smalt has degraded, causing these areas to appear blanched and hazy, while increased transparency of the dark parts of the figures and their draperies has given the picture a rather sunken look.

Marjorie E. Wieseman is Curator of Dutch paintings at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

A. Roy and B. Berrie, 'A new lead-based yellow in the seventeenth century' in 'Painting Techniques: History, Materials and Studio Practice', IIC Dublin Congress, A. Roy and P. Smith (eds), 1998, pp. 160–5

M.E. Wieseman, ‘A Closer Look: Deceptions and Discoveries’, London 2010, pp. 46–9

H. Wine, ‘National Gallery Catalogues. The Seventeenth Century French Paintings’, London 2001, pp. 16–23