Lodovico Mazzolino (active 1504–about 1528/30)

'Christ disputing with the Doctors', probably about 1520–5

Oil on wood, 31.1 x 22.2 cm

NG1495

'Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery', probably 1522

Oil on wood, 46 x 30.8 cm

NG641

The Ferrarese artist Lodovico Mazzolino became famous for his ornate devotional paintings of New Testament scenes set within fantastical architectural complexes. These structures emulate contemporary funerary monuments, ciboria (Eucharist vessels) and rood screens, and often include bas-reliefs inspired by Ancient Roman and Greek sarcophagi. Richly coloured and meticulously painted figures with exotic features and grimacing facial expressions reflect the stylistic influence of his probable teachers Ercole de’ Roberti and Lorenzo Costa,1 and suggest that Mazzolino also looked to Northern European artists, notably Dürer, whose works he would have known through prints.

Mazzolino painted these two works as a mature artist. ‘Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery’ is dated 15XXII in shell gold.2 The stylistic and thematic similarities between this work and ‘Christ disputing with the Doctors’ suggest that they are close in date.

Christ disputing with the Doctors

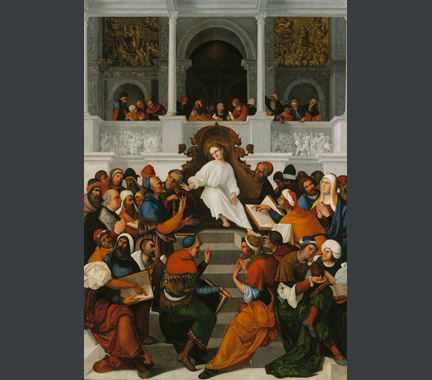

‘Christ disputing with the Doctors’ illustrates a story told in Luke’s Gospel (2:41–51). On their way home from Passover, Mary and Joseph did not realise that their 12-year-old son had stayed behind. Returning to Jerusalem, they found Jesus there debating with a crowd of doctors before the Temple of Solomon (the archetypal site of wise judgement). Mazzolino represents the moment when Mary and Joseph arrive. Jesus is elevated on a gilded throne decorated with sphinxes, a common symbol of knowledge, in order to emphasise his godly wisdom. His serene youthful face presents a stark contrast to the exaggerated expressions of the scholars, who are portrayed reading, debating and gesticulating. While the Bible places this scene in the court before the temple, Mazzolino situates it under the temple portico. The foreground piers supporting the portico roof also frame the picture. Behind the crowd of doctors a large opening, flanked by two pink marble Corinthian columns and sculptures in niches, leads into the inner part of the temple and the Holy of Holies.3 The Old Testament recounts how King Solomon had an inner room built in the temple to house the Ark of the Covenant containing the tablets with the Ten Commandments (1 Kings 6:19). Tellingly, Mazzolino depicts a frieze on the front of his structure representing Moses showing the tablets to his people, alluding to the treasure hidden behind the inner room’s walls. To underscore the importance of the building, Mazzolino includes a Hebrew inscription in the lunette above the frieze: ‘The House which Solomon built for the Lord’ (1 Kings 6:2).

Unfortunately, no archaeological evidence survives for Solomon’s Temple, but reconstructions after descriptions and plans of similar buildings do not resemble Mazzolino’s centralised structure with a cupola (the only one in his oeuvre). His interpretation of Solomon’s Temple recalls representations of Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the Dome of the Rock, both with prominent cupolae. The domed structure in this painting is only portrayed up to its circular drum. This is partly hidden behind the pediment that surmounts the portico, crowned with a roundel which appears to show Moses holding the tablets. The pediment contains a relief representing a battle scene which Mazzolino composed from individual figures copied from ancient sarcophagi. Deviating from generic representations of combat, the artist includes the young David in the centre of the frieze. David pulls towards him the head of his older bearded enemy Goliath.

The identification of the figures with these two Old Testament protagonists becomes more apparent in comparison with Mazzolino’s large-scale altarpiece of the same New Testament story, painted in 1524 for the family chapel of Francesco Caprara in the church of San Francesco in Bologna (now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin). In this altarpiece, the balustrades behind Christ’s throne are decorated with battle scenes featuring Judith with the head of Holofernes on Jesus’ right, and David about to decapitate Goliath to his left. David embodies the triumph of intelligence over physical strength in a way that parallels the young Christ’s victory over erudite scholars by teaching the word of God his father. In the National Gallery picture the visual link with David positioned directly above Christ reinforces Jesus’ authority in this context as he is a descendant of David and Solomon. The architecture as a whole emphasises the centrality of Jesus, while the narrative sculptural elements in grisaille it accommodates provide the Old Testament background to the colourful vibrant New Testament story.

Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery

Another Biblical subject Mazzolino returned to on several occasions was Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery, an episode narrated in the Gospel of John (8:1–11). The Pharisees asked Christ to condone the stoning of a woman taken in adultery, as stipulated in the Ten Commandments. In the National Gallery painting, Moses is evoked by the two bronze roundels on the temple façade, which show Moses with the tablets (on the left), and Moses among the Elders (on the right). The Pharisees intended to use this episode to create a trap for Christ, but rather than replying directly, Christ ‘stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not’ (John 8:6). Mazzolino depicts the subsequent moment when Christ responds: ‘He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.’ (John 8:7).

The Hebrew inscription on the steps reproduces this statement, a moment of artistic licence on Mazzolino’s part as the Gospel does not reveal the words Christ wrote on the ground.4 The crowd of Pharisees surrounding Christ and the adulteress in the court of the temple extends to the gallery, where scribes and Pharisees gather under the portico. The fictive architecture decorated with grotesques, bronze roundels and reliefs resembles a communal palace, a site where man-made law is enforced, rather than a temple. The shallow steps in the foreground lead up to the ground level where Christ stands, while stairs leading up to the arched entrance are presumably placed either side of the gallery’s projecting parts, each peopled with three Pharisees who look down on the event in the court. Columns and pilasters support the portico, surmounted by a bronze relief representing a battle scene set against a mosaic-like background. The view through the arched doorway suggests an arcaded inner structure. Instead of a welcoming house of God, Mazzolino represents the temple as an impregnable fort of Old Testament beliefs. This architectural device emphasises the division between the Old Law (represented by the doctors) and the New Law (Christ), which is central to the Gospel story depicted here. Mazzolino has used single-point perspective to draw the viewer’s eye towards the arched doorway, but he also gives the impression that the Temple is impenetrable, as entrance to it is blocked by the Pharisees who stand before it, and there are no steps providing easy access.

Paraphrasing antique motifs

Despite his careful articulation of architectural space, the elaborate architecture in Mazzolino’s works does not evoke actual buildings. They resemble stage sets designed to allow different narrative moments to unfold, both carved in stone and in the flesh. The sophistication of Mazzolino’s paintings appealed to his clientèle, which included several members of the Este court in Ferrara.5 The fictive Old Testament reliefs incorporated into the architecture allude to the associations between the Old and New Laws. The representation of Moses showing the tablets with the Ten Commandments associates Mazzolino’s building with the Temple of Solomon and with the Holy of Holies where the tablets were enshrined. In ‘Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery’, the inclusion of Moses with the tablets evokes the seventh commandment, against adultery, which the Pharisees appeal to.

The Hebrew inscription in ‘Christ disputing with the Doctors’ also enables identification of the building as the Temple of Solomon. Mazzolino made frequent and sophisticated use of Hebrew, which probably suggests the erudition of his patrons.6 Humanist circles would have understood the Hebrew as an element underscoring the historic and geographic authenticity of these paintings. Similarly, the prominence Mazzolino gives to reliefs inspired by Roman sarcophagi shows him targeting an educated audience that appreciated citations from antiquity.7

Mazzolino’s main source of inspiration for the battle scenes were sarcophagi decorated with ‘amazonomachy’ reliefs, portraying mythical battles between the Ancient Greeks and Amazons (a nation of all-female warriors).8 In his early depiction of the ‘Holy Family with Saints Sebastian and Roch’ (current location unknown)9 Mazzolino shows a motif found on sarcophagi fragments today in Mantua10 and in the Antikensammlung in Berlin.11 The same group of battling warriors and horses features on the left side of the central frieze in the National Gallery’s ‘Holy Family with Saint Nicholas of Tolentino’ (fig. 2).

On other occasions, Mazzolino paraphrased antique motifs, rather than directly copying an ancient source. For instance, the figure of the warrior on foot in the middle of the bronze frieze in ‘Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery’, whose pose is reminiscent of the Borghese gladiator, appears in several ancient sarcophagi and features in numerous compositions by the artist. The horse fallen to the ground with its head thrown back in horror at the far left of the central frieze in the ‘Holy Family with Saint Nicholas of Tolentino’ appears in the friezes of both paintings discussed in this catalogue entry. It seems that Mazzolino drew upon a repertoire of human and animal figures from drawings, prints and model books of ancient reliefs and sculptures in his studio.

Mazzolino used multiple textual, figural and artistic sources to visually and intellectually enrich his painted narratives. The Old Testament scenes and protagonists depicted in the reliefs in these pictures define the structures they adorn. They also identify particular functions for the buildings depicted. For instance, carvings featuring Moses with the tablets draw attention to the civic purpose of the Temple as a place that enshrined the law. Carved in stone or moulded in fictive bronze these reliefs belong to a different reality from the New Testament figures depicted in the flesh. This allows the artist to address the complex connections between the Old and New Testaments. Mazzolino imaginatively conceived his architectural settings to create a unifying structural framework, which brings together individual features in one complex yet coherent narrative, at once visually pleasing and intellectually challenging.

Arnika Schmidt

Selected literature

Robert 1890; Bober 1957; Zamboni 1968; Gould 1975; Haitovsky 1999; Bober and Rubinstein 2010; Mancini, in Penny, Mancini, Billinge and Spring forthcoming.

This material was published to coincide with the National Gallery exhibition 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting'.

To cite this essay we suggest using

Arnika Schmidt, ‘Ludovico Mazzolino, Christ Disputing with the Doctors’ published online 2014, in 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting', The National Gallery, London, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/place-making/mazzolino-christ-disputing-with-the-doctors