Author: Amanda Lillie

4. Open house, open church: architectural dissection

When representing whole buildings we might expect painters to have been concerned with what was most publicly visible – their façades and exterior walls,16 but from the late 13th century artists often chose to strip away whole façades to reveal the inside of buildings, creating holistic structures that fused interior and exterior and could be described as perspectival sections.17 Systematic and precise use of orthogonal projection was first seen in designs for St Peter's in Rome by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger from 1517; but before this, painters and architects shared in exploring the perspectival rendering of interiors, which was fundamentally a pictorial method.

An embryonic example of this comprehensive approach to architectural representation can be seen in Apollonio di Giovanni's ‘Assassination and Funeral of Julius Caesar’ (about 1455–60) where four episodes and four architecturally defined Roman sites are lined up for the spectator like a menu of different options for seeing the outside and inside of buildings (fig. 28).18 On the left, the Temple of Apollo is set up as a partial façade framed by a giant order of Corinthian pilasters with a deep niche scooped out to contain the sacred effigy of Apollo, and a grand doorway leading to the inner recesses of the temple (fig. 29).

The central building of the panel, set back from the picture plane, is an exterior view of the Pantheon with its portico stripped away, so that we see the two large niches either side of its main door, as well as its triangular pediment on the façade, behind which we see the great cylindrical drum of its broad, shallow dome (fig. 30).

The third building, on the right, is a cutaway view of an interior with five walls of an octagon in which Julius Caesar is being assassinated (fig. 31).

Suetonius described the assassination taking place in the Hall (or Theatre) of Pompey, where the Senate temporarily sat while Caesar was rebuilding the Curia in the Roman Forum.19 Apollonio chose features developed from Brunelleschi’s modern Basilica of San Lorenzo – tall grey stone fluted pilasters with Corinthian capitals, entablatures, round arched windows, oculi, and a deep curved niche where the high altar would be – perhaps in the knowledge that basilicas functioned as tribunals in Ancient Rome, and this was how he imagined the meeting hall of the Senate. But he gave the building an octagonal plan like the Florence Baptistery, and extended its floor to create an apron from the three remaining sections of the octagon, so that it projects beyond the basilica’s pilasters towards the audience, and is raised up on a moulded plinth.20

Any illusion of historical time and place is dispelled as we see a stage and painted actors performing the death of Julius Caesar. The final scene of Caesar’s funeral takes place on the far right in front of a monumental Roman column, alluding to the columns of Marcus Aurelius and Trajan, and a further façade with applied columns framing niches behind, resembling the ground floor of the Colosseum (fig. 32).

The artist exploited the long horizontal strip of the cassone panel to create a powerful sequence of monumental structures all ranged parallel to the picture plane. They were not accurate representations of Roman buildings, but their basic forms, their mass and presence, convey the essence of Ancient Rome as it was imagined in the mid-15th century.21 The buildings, each of a distinct and different type, each with its own geometric shape, are linked through the architectural theme of the scooped out, curvilinear niche (set between applied columns or pilasters), seven of them straddling the panel like a chain. Most important for the narrative and the viewing process is the way in which the buildings frame the action like four small stage sets, and the way the architecture pushes the figures and the drama forwards so that even the two interiors – the Temple of Apollo and the Hall of the Roman Senate – are treated like exteriors and stay near the surface. In this case the architecture ensures that rather than us entering the picture, the picture advances towards us, like street theatre performed very close.

Apollonio’s sequence of differentiated building types is no longer merely a visual description of buildings, but displays a painter’s analytical approach to architecture and to architectural representation. But other artists adopted a still more forensic or anatomical approach, removing façades to open up and explore not only interior rooms and spaces, but also the underlying structural elements of the building, its skeleton, in what we now describe as a transverse section.22 These cutaways or skeletal frameworks had already appeared in the late 13th century, in the frescoes of the Upper Church of San Francesco at Assisi painted by Giotto and his workshop.23 During the 14th century they had been taken up by artists’ workshops and were widely disseminated, as we can see in Taddeo Gaddi’s Santa Croce fresco and drawing ‘The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple’ (fig. 33).

This was a sort of radiology for artists. Their structures went beyond the bipolar separation of interior and exterior to create a true simultaneity of architectural forms, spaces and ideas, where openness and flow ruled over enclosure and division. Apart from fulfilling the crucial needs of narrative and of exploratory architectural design, sections through buildings could perform a special religious role for the congregation, as a revelation of hidden sacred space, enabling visual access to the inner sanctum of a saint’s world.

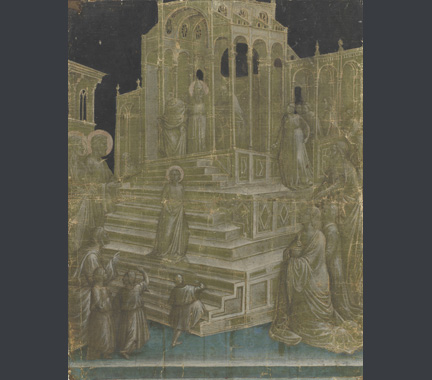

One of the best known explorations of this type was created by Lorenzo Ghiberti in his ‘Meeting of Solomon and Sheba’ panel (cast by 1437, chasing completed by1439) for his Gates of Paradise for the Florence Baptistery, where he stripped the façade away from the temple at ground floor level but let it re-emerge with its tabernacle windows on the first-storey level (fig. 34).24 Ghiberti set his building behind the figures so that it forms a backdrop to Solomon and Sheba, who join hands halfway up the front steps of the temple, on a landing behind a low wall which marks the crucial entry point to the temple precincts. By setting the temple further back he indicated its role as a destination for Sheba at the end of her long journey. At the same time Ghiberti created a staged entry motif for the panel, with an empty pathway leading through the centre towards Solomon and Sheba, and flat ground at the base surging towards five steps, a landing followed by four more steps, and another landing leading to a grille blocking the entrance to the inner sanctum beyond.25 These rising vertical levels work with the movement inwards from picture plane to pictorial depth conveyed by ever diminishing gradations of bronze relief. Yet despite the strictly controlled visual approach to the protagonists and the temple, the result is open and participatory. This is partly achieved by the public nature of the event depicted, with throngs of people flowing towards and around the meeting, and by the less tightly structured perspective, which, as Krautheimer showed, breaks Alberti’s rules.26

Above all, this inclusive effect is created by the open buildings: the cutaway temple façade with visual access to its nave, aisles, crossing and apse, all dissected for the viewer, flanked on both sides by buildings with tall loggias which are perspectivally splayed, creating an open-book type of composition. Scholars have tended to interpret perspective as a zooming inwards effect, narrowing towards the distance, but it is equally possible to see it as opening outwards towards the viewer. Each technique in this panel is designed to encourage visual access: the entrance pathway through a central opening via steps and platforms, the section through the temple, the outward splay of the basilica's aisles and the flanking buildings seen in perspective, and the design of the buildings with their proliferation of arches and apertures (at least 36 in this one panel).

Vecchietta (Lorenzo di Pietro) develops the cutaway façade or cross-sectioned basilica further in his ‘Story of the Blessed Sorore’ fresco, in the Sala del Pellegrinaio of Siena’s Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala (fig. 35).27 Like Ghiberti’s Temple of Solomon, the basilica of the Blessed Sorore is a vertical cross-section through the nave and aisles with the upper part of its façade still visible. However there are important differences, for Vecchietta brings his architecture forwards, creating an outer framework with pilasters supporting an arch spanning the whole wall as an entry point for the fresco, with two figures either side (one looking in and one looking out) inserted into the space between the entrance arch and the fictive basilica. As in Ghiberti’s temple, Vecchietta’s nave and aisles have ribbed cross vaults, but there are many further structural and decorative enrichments, such as the dome over the crossing, the shell niches and pilaster strips in the apsidal side chapels and main apse, and the coffering under the arches. Like Siena Cathedral, Vecchietta’s basilica is a decorative tour de force, with its splendid façade covered in illusionistic sculpture, surmounted by a Gothic tracery rose window (fig. 36).

Although executed in 1441, only two to four years after Ghiberti’s ‘Solomon’ panel, Vecchietta took the meta-motif of the basilica and created a virtuoso display of architectural and sculptural ornament transposed into painting. It is structurally aligned, but nothing could be further from the stripped down elegance of Ghiberti’s temple, which celebrates flat piers and pilasters, unarticulated walls and airy spaces – what Krautheimer described as ‘a classicistic and quiet purism’ (fig. 37).28 Vecchietta’s exuberant, hyper-inventive architecture dominates the picture plane (with its outer arch), the foreground (with the triumphal arch of the basilica façade), and every level of its deep space (with its many arches, dome and semi domes, piers and high imposts). Its multiple arches create successive frames and entrances, reinforcing the rhetorical nature of the picture, which explicitly and insistently addresses the viewer.29 It is a dynamic, even declamatory sort of construction, which applies sculpture lavishly to all its parts, and in the process creates a highly pictorial architecture. Although communication with the viewer seems paramount, what is being communicated – the narrative of the Blessed Sorore – is almost overwhelmed by the framing process itself.

Read further sections in this essay

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Painted boundaries, thresholds and inner frames

- 3. Apertures and arches, porches and loggias

- 5. Interiors: the picture as a room

To cite this essay we suggest using

Amanda Lillie, 'Entering the Picture' published online 2014, in 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting', The National Gallery, London, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/entering-the-picture/open-house-open-church