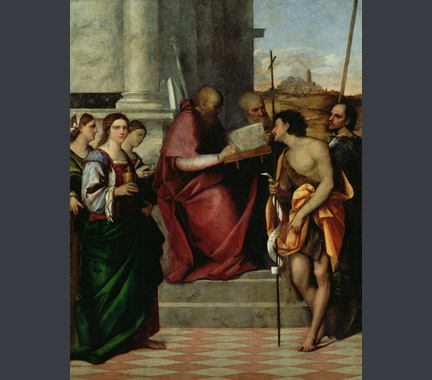

Sebastiano del Piombo (about 1485–1547)

'The Judgement of Solomon', about 1506–11

Oil on canvas, 208 x 315 cm

Kingston Lacy (Dorset), Bankes Collection, National Trust

© National Trust Images/Derrick E. Witty

This unfinished painting, widely accepted as the work of Sebastiano del Piombo, was one of the largest and most audacious narrative paintings produced in Venice in the early 16th century.1 It may have been commissioned for the grand reception hall (‘portegho’) of Andrea Loredan’s new palace designed by Mauro Codussi and completed around 1509.2 If this were the case, it would be an early example of a splendid type of painting in a horizontal format (later employed by Veronese) designed to embellish palace interiors. Its deep space and columns would have extended and enhanced the room.3

'The Judgement of Solomon’ was based on the Old Testament account (1 Kings 3: 16–28) describing how a mother who had accidently smothered her baby switched the dead child for the living child of another woman. Although the babies have not yet been painted, it is clear that Sebastiano depicts the response to King Solomon’s pronouncement that the living baby should be cut in half. The bad mother on our left points accusingly towards the good mother, while the good mother to the right has one hand on her heart and with the open palm of her other hand offers to give up her baby to save its life. The executioner in the right foreground was meant to hold the living baby in his left hand and the sword in his right. The divided composition with a central void and a clear parting of the figures into two camps is strengthened by the architecture with its nave and side aisles. This underscores the narrative: a stark choice or adjudication between two options concerning two babies, two mothers, truth and falsehood.

The compositional scheme

Three superimposed compositional schemes have been identified on this canvas, each successive phase becoming increasingly architectural 4 (see the essay 'Imagining the temple in Jerusalem'). The first phase with smaller figures included an open arch on the far right with blue sky and landscape visible through it, and two roundels either side of the throne. This is likely to have been an exterior or semi-exterior setting as it included a man on horseback to the right.5 The second phase introduced the cloth of honour in front of a deep arch, flanked by two large tabernacle-framed niches with segmental pediments, and the beginnings of a perspectival pavement with straight squares in the foreground.6 The third phase created a much more ambitious unifying composition which used perspective and architecture to create a magnificent basilica that encompasses the figures. The setting was now unequivocally an interior space.

The powerful architectural presence is partly the result of a relatively low viewpoint, so that we look up at the high steps, columns and vaults. The effect is also created by the perspectival pavement which extends continuously around the figures and towards the viewer. The interior elevation of the basilica dominates the picture. This architectural composition is similar to that adopted for many cutaway views of churches and temples; but whereas most of those have a longitudinal axis focused on the central nave, the great width of this canvas enabled Sebastiano to spread out his structure horizontally to include the aisles, which again contributes to the enveloping quality of the painting. By including a double row of columns on each side, and in particular by deploying free-standing columns for the outermost colonnade, Sebastiano introduces the possibility that this could be a double-aisled basilica.7 This might be a visual reference to the Ancient Roman basilica as a tribunal or law court. The inclusion of a stylobate, or stone platform to raise the height of the columns, and the trabeated, flat coffered ceilings (rather than arches and curved vaults) also set this apart from other representations of basilica or temple interiors.

The architecture compares closely with other works by Sebastiano, although the design of ‘The Judgement of Solomon’ is the most ambitious, and the one that most successfully enhances the subject matter. Sebastiano’s altarpiece for San Giovanni Crisostomo (fig. 1) employs similar red and white diamond paving in the foreground to place figures on a perspectival stage. In both pictures the principal figure is seated at the top of grey marble steps with receding colonnades of ‘all’antica’ columns raised on plinths, providing spatial depth and looming height, as well as lending authority and majesty to the central figure.

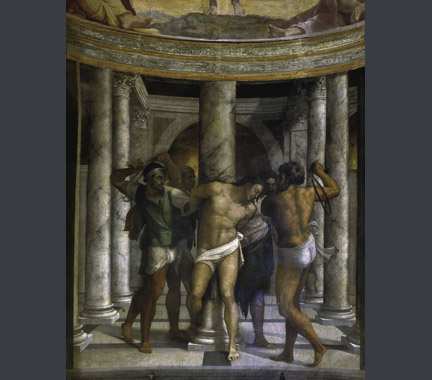

The external organ shutters for San Bartolomeo (fig. 2) share a very low viewpoint with ‘The Judgement of Solomon’, allowing us to see the underside of the Roman-looking coffered vault, and augmenting the apparent height of columns and arches. Here too we find a predilection for crisply moulded plinths and entablatures uniting the structure, and a sliver of architrave defining the upper edge of the picture.

Significantly, after his arrival in Rome Sebastiano retained the same architectural vocabulary, incorporating grey marble colonnades in his triple portrait with Ferry Carondolet and in the frescoed ‘Flagellation’ for the Borgherini chapel (fig. 3), which also seems to return to the apsidal scheme devised for the second phase of the Judgement of Solomon.

Amanda Lillie

Selected literature

Waagen 1857, pp. 377–8; Wilde 1974, pp. 99–102; Hirst 1981, pp. 13–23; Hirst in London (RA) 1983, cat. no. 97, pp. 210–1; Laing and Hirst 1986, pp. 273–83; Lucco in Rome and Berlin 2008, pp. 25, 27, 102–83; Harpur 2013.

This material was published in April 2014 to coincide with the National Gallery exhibition 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting'.

To cite this essay we suggest using

Amanda Lillie, ‘Sebastiano del Piombo, The Judgement of Solomon’ published online 2014, in 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting', The National Gallery, London, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/architectural-time/sebastiano-del-piombo-judgement-of-solomon