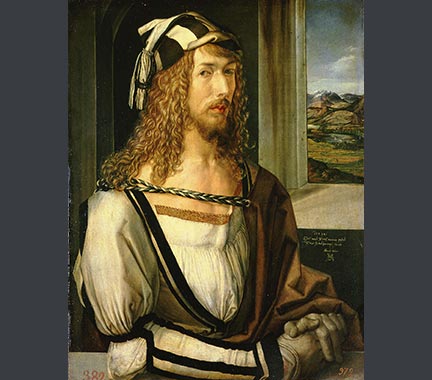

Attributed to Albrecht Dürer, 1471–1528

'The Painter's Father', 1497

Oil on lime, 51 x 40.3 cm

NG1938

In 1636 the city of Nuremberg presented Charles I with a pair of portraits by its most famous citizen, Albrecht Dürer: a self portrait and a portrait of the artist’s father. The second work would appear to be the painting now in the National Gallery. Scientific examination, meticulous connoisseurship and a thorough study of historic documents have begun to piece together the story surrounding this picture.

A royal provenance

In November 1636, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, visited the German city of Nuremberg. A companion described their visit to the city hall, which featured a room "furnished with several rare pictures, including two by Albrecht Dürer of himself and his father which the City fathers presented to his Excellency [Arundel]" as a present to King Charles I. The portraits entered the royal collection, but were sold following the execution of Charles I in 1649. The self portrait subsequently entered the Spanish royal collection (and is now in the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid), but the fate of the portrait of Dürer’s father is more obscure.

© The Art Archive / Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

The Painter’s Father came to the National Gallery in 1904 with little information about its earlier history. However, a thorough examination of the painting uncovered a possible clue. On the back of the wood panel support is a fragment of an old paper label, inscribed in what appears to be a 17th-century hand. The inscription on a similar label on the back of the Prado self portrait (perhaps in the same hand) makes it clear that the Prado painting, at least, had once belonged to Charles I.

The Gallery’s portrait precisely matches a description of the likeness of Dürer’s father in the royal collection, as listed in a 1639 inventory. The sitter is there described as having a black cap, and "a dark yellow gown wherein his hands are hidden in the wide sleeves painted upon a reddish ground all crack’t". Although other versions of the portrait are known, none have the same reddish background as the one in the National Gallery. The fact that the portrait is explicitly described as being ‘crack’t’ is also relevant. Most of the surface of ‘The Painter’s Father’ – and especially the background – is affected by broad, disfiguring cracks (now covered by modern retouching) that occurred as the paint dried.

Weighing the attribution

Although the National Gallery painting is considered the best of four known versions of ‘The Painter’s Father’, its quality and technique are not consistent with authentic works by Dürer. The streaky, pinkish-red background is unlike that in any other work by the artist. It was painted using madder, a red lake pigment that has faded over time, accentuating the streaky effect. Nor are the pronounced drying cracks seen in any other work by Dürer, whose meticulous application of successive layers of paint resulted in a flawlessly smooth surface. In contrast, the artist of the Gallery painting appears to have applied his paint quickly, in a single, relatively thick layer, which probably accounts for the extensive cracking.

© The Art Archive / Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid / Gianni Dagli Orti

A detailed comparison with paintings indisputably by Dürer – such as the self portrait in the Prado – makes it clear that the artist of the Gallery’s version lacks Dürer’s sophisticated and highly realistic approach to the modelling of form. The Gallery’s painting is likely to be a copy after a lost original by Dürer, probably made in the second half of the 16th century.

Value and significance

But if the Gallery’s painting can plausibly be identified with the painting given to Charles I by the city of Nuremberg, how could it be a copy? Admiration for Dürer’s work was such that copies were made of his paintings even during his lifetime, including some by the artist himself or made under his supervision. Production of copies, and their distribution, continued as his fame grew, well after his death. In 1636 the city fathers of Nuremberg may not have known, or cared, that one of the paintings they gave to the English king was a copy. It remained a valuable symbol of the achievements of one of their most illustrious citizens.

Marjorie E. Wieseman is Curator of Dutch paintings at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

S. Foister, ‘Dürer’s Nuremberg Legacy: The case of the National Gallery portrait of Dürer’s father’, a paper given at the conference ‘Albrecht Dürer and his Legacy’, British Museum, London, 21 March 2003. (PDF 301k)