Pieter de Hooch, 1629–1684

'A Man with Dead Birds, and Other Figures, in a Stable', about 1655

Oil on oak, 53.5 x 49.7 cm

NG3881

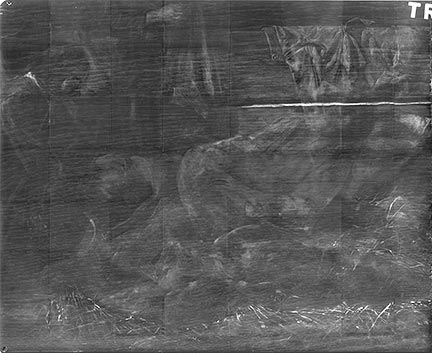

An X-radiograph of A Man with Dead Birds, taken in 1971, revealed that the still life of birds and hunting implements in the foreground was a later addition. At some point, someone had intentionally covered over part of de Hooch’s composition. A combination of scientific investigation and art historical sleuthing may have identified the culprit.

The humble setting and monochrome palette of this stable scene are typical of paintings produced by Pieter de Hooch around 1655. Nonetheless, in 1900 the painting was sold as a work by Jan Baptist Weenix, a 17th-century Dutch painter of game and bird still lifes, and was later described as a collaborative work by Weenix and de Hooch.

The idea that Weenix had had a hand in the picture was soon dismissed, but the changing attribution reflects the stylistic discrepancy between the richly painted still life in the foreground and the remainder of the picture, which is thinly painted and limited in palette.

Revealed by X-radiograph

In 1971 a scholar contacted the National Gallery with an inquiry: could the Gallery painting be connected with a lost painting by de Hooch of the same dimensions, described in an auction catalogue of 1825 as "a stable interior, in the foreground lies a wounded man who is being bandaged by a surgeon…"?

An X-radiograph showed that the spaniel and dead birds had been painted over the figure of a reclining man, positioned with his head near the panel’s right edge and his body laid almost parallel to the picture plane.

His bent right leg was supported by the hands of the man now seen to be plucking feathers from a bird. This dramatic discovery suggested the Gallery’s painting was indeed identical to the one mentioned in the auction catalogue.

A creative addition

The still life must have been added between 1825, when the painting was described as depicting a wounded man, and 1900, when it was sold in its present state. The buyer at the auction in 1825 was ‘Regemorter’ – probably the Antwerp painter Ignatius Van Regemorter (1795–1873), who specialised in anecdotal scenes reminiscent of 17th-century Dutch genre paintings.

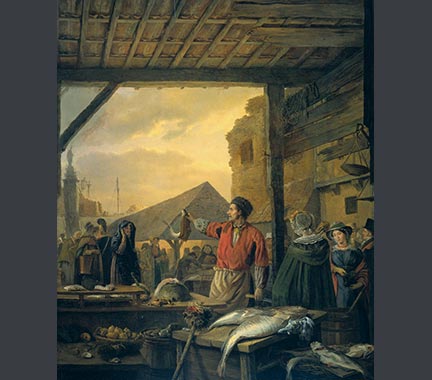

© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Both Ignatius and his father were also active as dealers, picture restorers and copyists – sometimes acting with more imagination than integrity. In 1797 a colleague noted that "Regemortel [sic] of Antwerp is ... making Ruisdaels, Pynackers, Boths, etc. He is very busy. Before long we will probably see an assortment of all those great masters, whose names he is good at putting on his overpainted pictures. It is a pity, I think, that honest folk are duped by this."

The Van Regemorters seem to have altered some of the 17th-century paintings that passed through their hands to suit contemporary taste. De Hooch’s choice of a rather sombre subject – a wounded man – may have prompted Van Regemorter to improve its ‘saleability’ by adding a colourful still life.

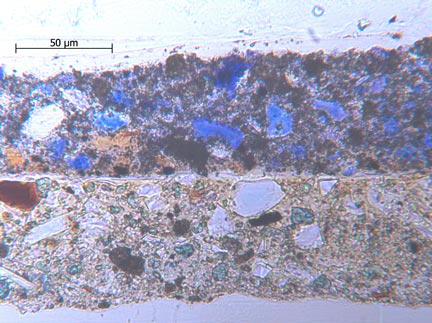

Technical investigation

In an effort to determine more precisely when the overpainting was done, in 2009 Gallery scientists took minute paint samples from a few key areas. Examined microscopically and by SEM-EDX, a cross-section of a sample taken from the greyish-blue plumage of the bird at lower right confirmed the main components of the uppermost (overpaint) layer to be natural ultramarine, Naples yellow, lead white, smalt and red earth.

Use of Naples yellow (lead-antimony yellow) replaced lead-tin yellow during the first quarter of the 18th century, and continued until the latter part of the 19th century. In contrast, a sample taken from an area of original paint was found to contain the lead-tin yellow commonly used by 17th-century (and early 18th-century) Dutch painters. Unfortunately, despite the presence of Naples yellow, the combination of pigments present in the area of overpaint does not allow it to be dated more specifically within the known parameters (1825–1900).

Marjorie E. Wieseman is Curator of Dutch paintings at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

R.E. Fleischer, ‘An Altered Painting by Pieter de Hooch’, ‘Oud Holland’ 90, 1976, pp. 108−14

N. Maclaren, ‘National Gallery Catalogues. The Dutch School 1600–1900’, rev. ed. by C. Brown, 2 vols, London 1991, vol. 1, pp. 202–3

P.C. Sutton, ‘Pieter de Hooch’, Ithaca 1980, cat. no. 14

M.E. Wieseman, ‘A Closer Look: Deceptions and Discoveries’, London 2010, pp. 78–81