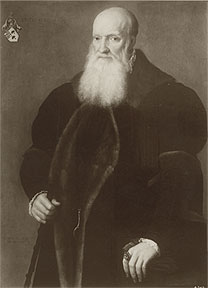

Attributed to Michiel Coxcie, 1499–1592

‘A Man with a Skull’, about 1560 or later

Oil on oak, 97.2 x 75.6 cm

NG195

Rarely has a painting acquired with such fanfare fallen from favour so swiftly, or with such dramatic consequences. Within weeks of its acquisition, the National Gallery’s first ‘Holbein’ was demoted and the Keeper responsible for the acquisition shamed. New research may have discovered the identity of the painter who created this distinguished portrait.

Scandal and shame

A Man with a Skull was purchased in April 1845 as a work by Hans Holbein the Younger. Although German by birth, Holbein had worked in England for many years, and in the 19th century was widely regarded as the first great British artist. As this iconic painter was not then represented in the Gallery’s collection, the acquisition of a work by him was an event of national significance.

From the moment this painting was installed in the Gallery, however, a cloud of suspicion surrounded it. Critics were quick to point out the painting’s deficiencies: it lacked the assured draftsmanship and strong characterisation that distinguish a true Holbein. Newspaper accounts decried the expenditure of public money on a painting whose attribution was in question. The painting remained on display, but the optimistic ‘Holbein’ label was quickly dropped. The Keeper responsible for the acquisition, Sir Charles Lock Eastlake, was shattered by the scandal, and ‘the Holbein affair’ proved a major factor in his resignation barely two years later.

The search for an attribution

For more than a century and a half, ‘A Man with a Skull’ remained a painting in search of an author. Tentative and unconvincing attributions were made to a host of 16th-century painters, both Flemish and German. In 1945 National Gallery curator Martin Davies even suggested that it might be an early 19th-century fake. More recently the painting was catalogued as ‘Style of Nicolas de Neufchâtel’.

Science and connoisseurship

In 1993 dendrochronological analysis provided support for the view that while Holbein could not possibly have painted the portrait, neither was it a later fake. The painting’s oak panel support is composed of three boards, with the latest growth rings formed in 1542 and 1543. Allowing for trimmed sapwood (outer) rings, and for storage time to season the wood, a date of 1560 or later for the painting is likely – well after Holbein’s death in 1543. The painting is an authentic work of the 16th century, but who painted it?

Formerly collection Comte de Brouchoven de Bergeyck, Antwerp (now lost)

Recent research, part of the Gallery’s ongoing programme of recataloguing the permanent collection, may have found the answer. The physical evidence and the coat of arms at upper left indicate that the painting was made in or near Brussels in about 1560. Two portraitists of note were active in the city at that time, the more important being Michiel Coxcie (1499–1592).

Coxcie’s portraits of the 1550s and 1560s display a uniform delineation of the upper and lower eyelids, and rather large, poorly drawn hands with stiff, sausage-like fingers. Both features are evident in ‘A Man with a Skull’. Further research into the coat of arms at upper left will hopefully yield an equally precise identification of the portrait’s distinguished subject.

Extensive underdrawing

Infrared reflectograms of ‘A Man with a Skull’ reveal two types of underdrawing, both executed in a liquid medium applied with a brush. The head and facial features are simply drawn with no major changes, and have probably been mechanically transferred from a study drawn on paper. Clothes, hands and skull are sketched freehand in a much bolder style and show changes, especially in the hands and skull.

The combination of two underdrawing techniques is not unusual in portraits of the 16th century. Future comparison of underdrawings in other portraits by Coxcie may help to confirm the proposed attribution.

Marjorie E. Wieseman is Curator of Dutch paintings at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

To be included in L. Campbell, ‘National Gallery Catalogues. The Sixteenth Century Netherlandish Schools’, London (forthcoming)

D. Robertson, ‘Sir Charles Eastlake and the Victorian Art World’, Princeton 1978, pp. 83–6

M.E. Wieseman, ‘A Closer Look: Deceptions and Discoveries’, London 2010, pp. 50–2