Structure and reconstruction of the altarpiece

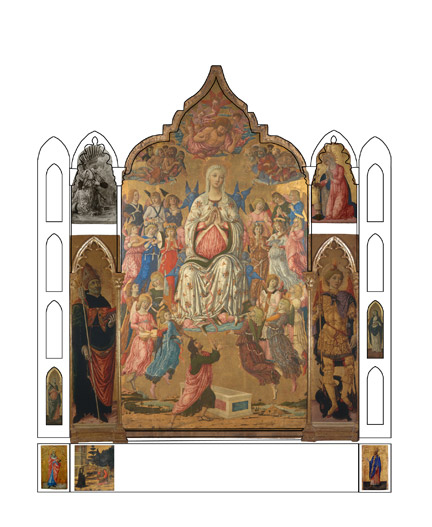

An original location in Sant'Agostino in Asciano (Fig.15) is consistent with the structure of the altarpiece. Although it has been argued that NG 1155 was intended to stand alone,15 Romagnoli’s early nineteenth-century account shows that the altar must have been a polyptych containing an unspecified number of subsidiary panels (‘di molti comparti che la Tavola comprendeva’).16 Hartlaub tentatively suggested that the 'Assumption' could be connected with Matteo's pictures in the Museo di Palazzo Corboli, Asciano of 'Saint Augustine' (the name saint of the convent) and 'Saint Michael' (a local patron saint whose name was used for the nearby valley) (Figs. 16 and 17). These works are still in their original frames, and are now are falsely married to Giovanni di Paolo’s much smaller 'Assumption'.17 The saints are depicted on tall rectangular panels with spandrels at their tops creating pointed arches. The panels must have continued above these arches, but their tops were at some stage rather brutally sawn off, plausibly at the moment when the 'new' altarpiece incorporating Giovanni di Paolo’s painting was constructed.

The lateral saints and upper panels

The two saints have a physical presence like that of the Virgin in the National Gallery’s 'Assumption'. Augustine is endowed with severe monumentality and Michael has a remarkable springiness. His calm expression and the shape of his head echo Mary's. The Asciano panels are, like the 'Assumption' itself, pictures of great power and imagination. Matteo has dazzlingly exploited the varied possibilities of different gilding techniques for the 'Saint Michael' (Fig. 17). The use of dark glazes painted over the gilding for volume and incision for ornament make his fantastic 'all'antica' armour truly astonishing (Fig.18).

When John Pope-Hennessy re-elaborated Hartlaub’s hypothesis, he declared that (after cleaning) there was 'no doubt' that the 'Saint Michael' and the 'Saint Augustine' functioned respectively as the inner and outer panels on the left side of the 'Assumption' – and that two more lateral panels were once placed to the right of the central scene. Assuming four side panels in total, he suggested that the altarpiece might have measured 'almost four metres' in width. He added that there was a strong possibility that two of the altarpiece's 'upper panels' – by which he almost certainly meant crowning pinnacles – were the damaged 'Archangel Gabriel' (Fig. 19) that appeared on the New York market in 1926, its whereabouts now unknown, and the 'Virgin Annunciate' (Rhode Island School of Design, Museum of Art, Fig. 20).18 Though cut down into its present shape, the width of the 'Virgin Annunciate' at its base makes it very possible that it was set above the 'Saint Michael' (Fig. 23). As with the rest of the picture, the lighting source is from the left and Pope-Hennessy rightly argued that the 'Virgin Annunciate' is a twin to the Virgin in NG 1155 (Figs. 21 and 22). Compelling parallels can be drawn between the oval shape and modelling of her head, the specific treatment of facial features like the slightly down-turned mouth, rosy cheeks and bruised eyelids, and the vertical folds of her dress as it falls over her belly. She even has the same sleeves, revealing her underdress at the wrists, and transparent veil covering her blond hair. Only her cloak has changed – necessarily, to show her in these different roles.

NG 1155’s head and belly with the

‘Virgin Annunciate' (fig. 22)

However, Ludwin Paardekooper corrected Pope-Hennessy in one important respect, noting that the ‘Saint Michael’ (Fig. 23) is a right-hand lateral panel rather than a second left-hand one.19 ‘Saint Augustine’ (Fig. 24) would indeed more probably, as the name-saint of the church, have been positioned to the immediate left of the centre panel, at the Virgin’s right hand in the place of honour.

Before the exhibition in 2007 we had the opportunity, thanks to the generosity of the owners of the individual paintings, to examine ‘Saint Michael’, ‘Saint Augustine’ and the ‘Virgin Annunciate’ in the Conservation Department of the National Gallery.

On the left and right respectively the capitals of the frames of ‘Saint Augustine’ (Fig. 25) and ‘Saint Michael’ (Fig. 26) are flush with the rest of the frame, but to the right of Augustine’s head and to the left of Michael’s, the capitals project beyond the frame edges and would have overlapped the painted surface of Matteo’s central panel. Repainting was discovered on the 'Assumption' at the points where the frames would have overlapped. These repaints were applied to cover where the framing elements had been originally. Fig. 27 shows the repainted area to the right of the ‘Assumption’, which was covered by the projecting capitals still attached to the frame of ‘Saint Michael’. Measurements of the positions of the dowels set into the edges of the central and side panels confirmed the alignment of these pictures (Figs. 28, 29 and 30).

The battens which remain on the ‘Assumption’ have been cut. It was possible to show that they continued across the backs of ‘Saint Michael’ and ‘Saint Augustine’. In the left edge of the ‘Virgin Annunciate’ there is a dowel hole (Fig. 31) which may be lined up with a dowel hole visible near the top of the right side of the 'Assumption' (Fig. 32). This enabled us to understand how these two pictures were aligned in Matteo’s altarpiece for Asciano.

The panels have been arranged in our reconstruction to conform with the positions suggested by the evidence of the original placement of the dowels and of the battens (Fig. 33).

The total width of the altarpiece would therefore have been approximately 3.10 metres. Although the Gothic church of Sant'Agostino is now somewhat changed, the pointed entrance arch to its choir or presbytery, where the Augustinian monks would have been seated during the Mass, behind the high altar on which the altarpiece was surely placed, is unaltered (Fig. 34). This entrance arch has a width of 4.8 metres, comfortably accommodating the altarpiece.

The framing pilasters and the predella

Further surviving pictures by Matteo may plausibly be added to this reconstruction. These are works which seem to have been painted on the side pilasters or buttresses and on the predella.

a) The side pilasters

Two panels survive in a private collection (Fig. 35) from the pilasters which would have flanked the three main panels of this altarpiece, NG 1155, ‘Saint Michael’ and ‘Saint Augustine’. These pictures represent Saint Agatha and Saint Lucy.20 They are painted on two smallish rectangular panels which have been stuck together, probably in the mid-nineteenth century. The particular refinement with which the two women are painted – the lovely transparent veil over Agatha’s hair, the little corkscrew of curls that touches her long neck (Fig. 36), the elegant bounce of Lucy’s hairstyle (Fig. 37), the tapering fingers of both – link these panels to the lateral saints, Michael and Augustine (Fig. 38), from the Asciano altarpiece. All these pictures share a sensitive pale highlighting and the delicate dark contour line used around areas of flesh painting, especially in the hands.

It has long been supposed that Saints Agatha and Lucy were once the lateral sections of a small triptych.21 However, following Trimpi's suggestion that they came from a larger altarpiece complex, several candidates have been suggested, including the National Gallery 'Assumption' (Fig. 1).22 The underdrawing which has been revealed by IRR under these beautiful little pictures is by the same hand as that responsible for some of the underdrawing of the main panel of the polyptych.

The two figures of Saints Agatha and Lucy (Fig. 39) are of different heights and whereas the head and upper body of Saint Agatha are depicted as if the spectator is standing directly before her, in such a way that we view the tops of her feet, Saint Lucy, looking down, is best viewed from below. We see the underside of her dish and the back of her right hand holding it. While Lucy is mostly paint, much more gold can be seen in the figure of Saint Agatha. This implies that Saint Lucy was originally seen from below and further away, and that the two saints were placed at different levels on the two tall side-pilasters. Typically, small saints were painted on these, one above another in series of three or more. 'Saint Agatha' would have been in the lowest position on the left, 'Saint Lucy' higher up on the other side (Fig. 40). Saint Agatha's greater prominence might be explained by the fact that Asciano's second important church is dedicated to her. It was quite usual to pay tribute in one church to a neighbouring foundation in this way, by placing the image in a subsidiary part of an altarpiece.

b) The predella

No extant fragment was associated with the predella of the altarpiece until Luke Syson's recent suggestion that a gold-ground panel at Villa I Tatti, Florence (Berenson Collection) of 'Saint Monica praying for the Conversion of her son Augustine' (Fig. 41) may have been part of it.23 The rare subject of this panel, based on Lippo Vanni’s fresco in the church of the Augustinian hermitage of San Leonardo al Lago near Siena,24 perfectly suits the context of an Augustinian altarpiece. The scene is painted on a thick wood panel with horizontal grain, which suggests that it is indeed a predella fragment. It is consistent with the main panels of the altarpiece in style and in the use of a gilded background, and the unusual height of the painted surface, a full 42 centimetres,25 links the picture with great probability to the Asciano altarpiece, the largest that Matteo ever executed. There must have been other narrative scenes painted on the horizontal board of the predella, but none of these has yet been found.26

However, two paintings, representing 'Saint Jerome' (Fig. 42, Christian Museum, Esztergom) and 'Saint Nicholas' (Fig. 43, Lindenau-Museum, Altenburg) can be shown to be pilaster bases, or pedestals.27 Physical evidence proves that these two small panels, both painted on wood with a vertical grain, were originally glued and nailed to a horizontal board.28 Since they are also gilded on their inner sides, and painted a dark claret colour on their outer sides – a treatment commonly used for pilaster bases – they must have been positioned originally as projecting elements at the left and right ends of a predella.

The connection of 'Saint Jerome' (Fig. 44) and 'Saint Nicholas' to the Asciano altarpiece is hypothetical as they are not evidently linked to it through their iconography, and there is no scholarly consensus regarding their date.29 Their style, however, shows very close parallels with the male saints in NG 1155 (Fig. 45) in their similar facial features, including the dark flesh tones, the creased, parchment-like skin, and the confidently drawn contours. The Esztergom and Altenburg fragments originally measured about 42.5–43 x 25 centimetres, which perfectly matches the Villa I Tatti panel of 'Saint Monica'.30 The extreme rarity of such large structures in Sienese art, where the standard height for predellas was about 25–35 centimetres, adds weight to the hypothesis that all three of these fragments were once part of Matteo di Giovanni’s Augustinian altarpiece at Asciano.31

Conclusion

The reunion of many of the constituent parts of the Sant’Agostino polyptych in ‘Renaissance Siena: Art for a City’ at the National Gallery in 2007–08 was an important achievement. Yet it was – as exhibitions often are – a beginning rather than an end. This publication presents the current state of our research in 2013 into this subject. The opportunity to conduct technical examinations on the paintings which came to the London exhibition in 2007-08 – ‘Saint Michael’, ‘Saint Augustine’, ‘Saints Lucy and Agatha’, and the ‘Virgin Annunciate’ – was invaluable, and has enabled the reconstruction presented in these pages to be refined and developed in 2013. We would like to thank the owners of these pictures for their kindness, and their commitment to this project. We have also benefitted from the generosity of Dr Dóra Sallay, who has shared her research with us, and who has improved immeasurably this text. Most of all, however, we thank and acknowledge the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, whose support has made this project – and its publication – possible.

We hope that future research, particularly into the underdrawing of the predella panels, will further enrich and improve our understanding of Matteo di Giovanni’s Asciano altarpiece, one of the most extraordinary pictorial ensembles to survive from fifteenth-century Siena.

This text is based on Luke Syson, ‘The Asciano Altarpiece, 1474’ in Luke Syson, ‘Renaissance Siena. Art for a City’, exh. cat., London, The National Gallery, 2007-08, pp. 124-31 with additions by Rachel Billinge and Caroline Campbell. The section, ‘The predella’, and the Appendix have been written by Dóra Sallay. We gratefully acknowledge Dr Sallay’s active participation in the editing of the text.

Further Sections

- Introduction

- Iconography

- Precedents and influences

- Structure and reconstruction of the altarpiece

- Appendix: Travel notes of Ettore Romagnoli

- Bibliography

16. The “four or five works” Romagnoli’s refers to in his travel notes of 1800 and in his later biography of Giovanni d’Asciano (see Appendix) most likely refer to the same panels.

17. Hartlaub 1910, pp. 72, 78. Matteo’s pictures were joined with Giovanni di Paolo’s ‘Assumption’ some time before 1865, when Francesco Brogi recorded them together in the Collegiata of Sant’Agata in Asciano (Brogi 1897, p. 12).

18. Pope-Hennessy 1950.

19. Paardekooper 2002, p. 36, note 78.

20. Trimpi 1987, pp. 103-04, no. A7.

21. H. Brigstocke in Weston-Lewis 2000, pp. 82-83, cat. 21.

22. Trimpi 1987, pp. 103-04, no. A7.

23. Syson, in London 2007-08, p. 131. For more on this panel, see the forthcoming catalogue of the Berenson collection at Villa I Tatti, edited by Carl B. Strehlke and Machtelt Israëls.

24. Cornice 1990, p. 308, fig. 34.

25. The present dimensions of the panel are 42 x 39.1 x 1–3.5 cm; the painted surface measures 42 x 38.8 cm. The support is a single panel that retains its original thickness. Fragments of a barbe prove that the painted surface has not been reduced on the left, top and right. At the bottom, the paint edge appears to have been slightly reduced.

26. As the intact edge of the paint, or barbe, along the right edge of the Villa I Tatti fragment shows, the scenes were once separated by moulded strips or small projecting panels.

27. Written communication of Dóra Sallay to Luke Syson (May 2007); Syson in London 2007–08, p. 131; Sallay 2008, pp. 7–8.

28. The nail holes, now repaired, are discernible in both panels at about mid-height along both vertical sides. Fragments of horizontally grained wood survive trapped in spots of glue on the back of the Altenburg fragment, proving that the piece was originally fastened onto a horizontal plank.

29. As the most likely date of execution for these two fragments, the majority of scholars suggested the 1460s, whereas Riccardo Massagli (in Boskovits and Tripps 2008, pp. 164–65, cat. 30) proposed the period c. 1455–60. Erica Trimpi (1987, pp. 93–95, no. 2, pp. 138–39, no. 29), however, claimed that because of the absence of the ‘hardness of form of Matteo’s early period’ they should be dated ‘somewhat later’, on the basis of a comparison with the predella of Matteo’s Celsi altarpiece of 1480.

30. The Esztergom fragment (41.2/41.6 x 25 x 1.2/1.4 cm, painted surface 40.8 x 25 cm) now misses about 2 cm of its painted field at the bottom. The Altenburg fragment measures 42.6 x 25.1 x 3.5/3.8 cm. The Tatti panel must have originally been close to c. 42.5-43 cm.

31. For a more detailed discussion of the Esztergom and Altenburg fragments, see Sallay forthcoming.