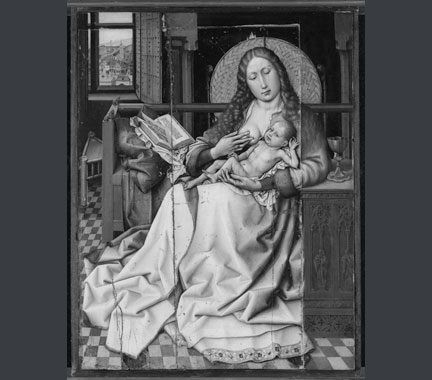

Follower of Robert Campin, 1378/9–1444

‘The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen’, about 1440

Oil with egg tempera on oak with walnut additions, 63.4 x 48.5 cm

NG2609

This tender depiction of the Virgin nursing the infant Christ was probably painted in the 1440s by a follower of the Flemish painter Robert Campin. It appears to be a fragment of a slightly larger painting, and seems also to have suffered some damage along the right side of the panel. Sometime before 1875 a restorer added strips to the top and right side of the painting, probably to replace these damaged areas.

Italian connections

The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen came to the National Gallery in 1910 as part of the bequest of George Salting. He had acquired the painting from a Belgian collector, who had purchased it in Venice in 1875. An 18th- or 19th-century inscription on the back of the oak panel support indicates that it was at one time owned by ‘conte balbiano’. The Balbiano family was from the town of Chieri, near Turin, home to many of the ‘Lombard’ moneylenders active in the Netherlands during the 15th century. It is possible that the Gallery’s painting may have descended to the Balbiano through a local family with Netherlandish connections.

An extensive restoration

Over time, 'The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen' had become obscured by dirt, darkened varnish and discoloured retouchings. Treatment was postponed until 1992 because of the complex problems posed by later additions to the original fragment. Sometime before 1875, when the painting was recorded in its present state, strips of wood had been added to the top and right side of the panel.

A burn mark at the right edge of the original panel, just below the Virgin’s fur cuff, suggests the painting may have been damaged in a fire. The added strip at the right, 9 cm wide and extending the whole height of the panel, includes the cupboard and chalice, the Virgin’s elbow and the right-hand portions of the fireplace and wicker screen. The addition at the top, 3 cm wide, includes the upper portion of the window and shutter, and part of the left side of the fireplace.

The composite X-radiograph shows that this wood is of a denser grain than the original panel. The short, light markings are worm channels that have been filled in with X-ray opaque material.

Aesthetic decisions, past and present

During treatment at the National Gallery, it was decided to keep the 19th-century additions to preserve the visual unity of the composition. These parts were retouched to appear fractionally darker than the original paint, so that they could be easily distinguished on normal viewing. Comparison of the Gallery’s ‘The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen’ with another version of the composition suggests that the 19th-century restorer crafted a much more elaborate cupboard at right and inserted an ornate chalice in place of a simple brass bowl. The restorer also painted out the top of the fireplace – all that remains is a thin streak above the Virgin’s head, the rest having been presumably trimmed away to allow the addition to be attached at the top – and prudishly masked the Christ Child’s genitalia. These now more closely approximate the original appearance.

Colour changes

Other changes have also affected the present look of the painting. The Virgin’s fur-lined robe and jewel-trimmed gown are painted with ultramarine mixed with a red lake pigment, probably madder, to produce purple. Over time the red lake component has faded, so that the robe is now less purple than it initially would have been. Because the highlighted portions of the drapery originally had less red lake pigment and a greater proportion of white than the shadows, the loss of colour has resulted in an increased contrast of light and shade in the Virgin’s garments.

Marjorie E. Wieseman is Curator of Dutch paintings at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

D. Bomford, with J. Dunkerton and M. Wyld, ‘A Closer Look: Conservation of Paintings’, London 2009, pp. 78–9

L. Campbell, ‘National Gallery Catalogues. The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools’, London 1998, pp. 92–9

L. Campbell, D. Bomford, A. Roy and R. White, ‘“The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen”: History, Examination and Treatment’, ‘The National Gallery Technical Bulletin’ 15, 1994, pp. 21–35 (also appears in S. Foister and S. Nash, eds, ‘Robert Campin: New Directions in Scholarship’, Turnhout 1996, pp. 37–54)