Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, 1796–1875

‘The Roman Campagna, with the Claudian Aqueduct’, probably 1826

Oil on paper, laid on canvas, 22.8 x 34 cm

NG3285

Sometimes the presence of a pigment with a well-defined date of introduction can prompt researchers to think again about the date traditionally given to a painting. In the case of Corot’s The Roman Campagna, with the Claudian Aqueduct, however, the painting can be so securely dated on stylistic grounds that the unexpected identification of the man-made pigment viridian meant revising the history of its usage.

In 1825 the young landscape painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot set out for Italy, following in the footsteps of generations of French artists who had undertaken a similar period of study in Italy to perfect their art. Like many of his predecessors, Corot spent his time sketching and painting the picturesque Italian landscape. His first trip into the countryside was probably made in May 1826, and it is likely that this study of the Claudian Aqueduct was made around that time.

Early developments

There are several reasons for assigning such a specific date to the painting. Corot made about 150 paintings during his three-year stay in Italy (1825–8). His artistic development during these years was swift and dramatic. Correlating the locations depicted in paintings and the evidence provided by drawings, notebooks and correspondence, it is possible to establish a chronological framework for these works.

In informal sketches such as the National Gallery’s painting, Corot aimed to capture the effects of the strong Mediterranean light on landscape and architectural forms in simple, lucid compositions. ‘The Roman Campagna, with the Claudian Aqueduct’ was probably made en plein air: it was painted on paper – easily transported – and later mounted on a stretched canvas for greater permanence. Possible pin holes at the upper and lower left corners (the right corners are damaged) suggest that before it was mounted on canvas, the painting might have been pinned to the wall.

Corot’s contemporaries admired his landscape sketches, and Corot frequently lent works like this to other artists to copy. This particular sketch was later owned by Edgar Degas.

A puzzling pigment

An infrared photograph shows that Corot first sketched some of the landscape forms, probably in crayon, before applying the paint.

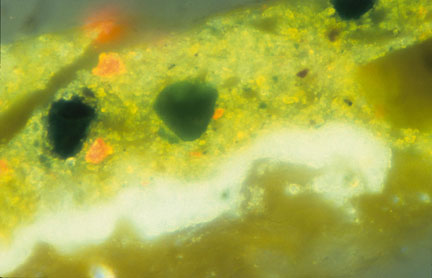

For the most part, the pigments he used were typical for the time, including vermilion, cobalt blue in the sky and lead white in the clouds. One notable exception is viridian, identified microscopically and by EDX in the mid-green strip extending from the left side of the composition and in the dull green of the foreground and the foliage on the right.

While sometimes the presence of a pigment with a known date of introduction causes scientists and curators to re-examine the date traditionally assigned to a painting, in this instance the reverse was true. On stylistic grounds Corot’s painting can be dated quite securely to early 1826, but viridian was thought to have been available to artists only from the 1830s.

Experimenting with colour

The artist-chemist Antoine-Claude Pannetier (1772–1859) was the first to manufacture the pigment viridian (hydrated chromium oxide), but he kept both the process and the exact date of its development secret. The pigment was first referred to in an artists’ manual published in 1833, which also noted that it could be obtained from the Parisian artists’ suppliers Colcomb-Bourgeois. Corot is documented as a customer there before he left for Italy in 1825, and while he was in Rome he asked a friend to send him colours from the shop.

The evidence of this painting would suggest that the elusive Pannetier had made his vivid new pigment available through Colcomb-Bourgeois at least by the mid-1820s. Corot used viridian in other paintings later in his career (for example, Peasants under the Trees at Dawn, about 1840−5, and The Oak in the Valley, 1871), but he always preferred to temper the harsh green by mixing it with other pigments.

Marjorie E. Wieseman is Curator of Dutch paintings at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

S. Herring, The Roman Campagna, with the Claudian Aqueduct

S. Herring, ‘Six Paintings by Corot: Methods, Materials and Sources’, ‘The National Gallery Technical Bulletin’ 30, 2009, pp. 86–111