Author: Amanda Lillie

4. Imagining the Temple in Jerusalem: an archetype with multiple iconographies

Since Solomon’s Temple was destroyed centuries before Christ and the only early record of its appearance is in the Old Testament,25 every depiction of the building was either an imitation of the Jerusalem Temple in one of its later rebuilt forms, or an imaginary evocation that drew on other artists, writers, pilgrims, theologians and preachers engaged in reconfiguring or evoking the essence of the ancient temple (fig. 32).26 For Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem is an ur-building, an archetype for countless other temples or religious structures, and for textual and verbal descriptions of them throughout the European and Mediterranean worlds. It was employed as a yardstick against which holiness, wisdom and beauty were measured, since all three concepts were united in the one structure. Part of its power derived from its non-existence. An idea propagated in complicated and ambiguous biblical texts left architects and artists freedom to invent their own temples. Rather than obliterating or replacing the original Temple of Solomon, repeated rebuilding on the site of the Temple Mount kept the memory of the original alive, as the ancient core was subsumed within each new version. The later Temples were (and are still) venerated as Solomon’s progeny. Drawings, prints, paintings, sculptures and other reproductions of the Temple could become part of a vast genealogy, disseminating the idea of the temple through the generations.27

Reconstructing a sacred site

The imagined architecture in many Renaissance paintings tends to follow specific formulae for specific religious subjects (such as the thrones of Madonnas and the stables and ancient ruins of Nativities), but Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem tapped into rich seams of artistic invention. The Temple connects Old and New Testaments. It lies at the heart of many different biblical stories and related feast days and appears in multiple depicted narratives. Among the most frequently represented are: the Meeting of Solomon and Sheba, the Judgement of Solomon, the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, Christ disputing with the Doctors, Christ driving the money-changers from the Temple, and Peter healing the lame man in the Temple Porch. Strictly speaking, representations of the Temple in narratives of the life of Christ and the Apostles ought to have employed Herod’s rebuilding of the Temple, but Renaissance depictions confused and merged the various reconstructions.

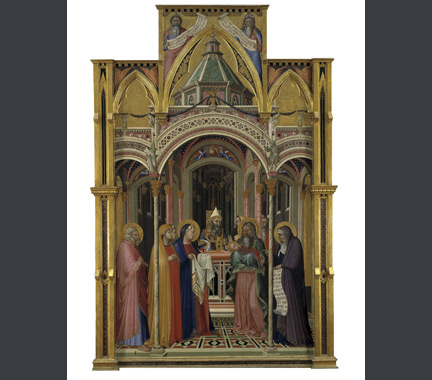

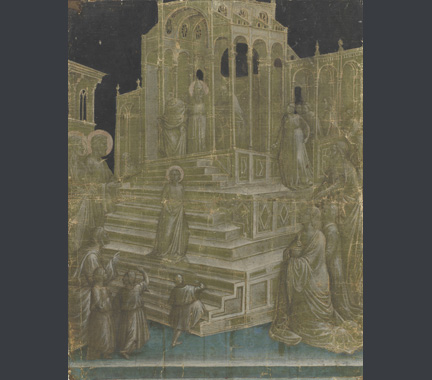

Despite the variety of subjects and architectural inventions, established solutions and compositional formulae helped artists to launch their creativity from a familiar base. For example, painters used the closely related architectural compositions devised for the Presentation of Christ and the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple as models for well over a century and a half, from about 1342 to about 1510 (see figs. 33 and 34).28 In these Presentation scenes the Temple was conceived as a basilican church, an architectural type that then became associated with Temple narratives in religious painting all over Italy.29 After the early 14th century this longitudinal type began to compete with centrally planned ‘tempietti’ derived from pilgrims’ accounts of the Dome of the Rock and the Holy Sepulchre.

The Temple porch

Other continuities are observable in the great diversity of Temple images. Certain parts of the temple were favoured, determined partly by the Bible, which refers to specific zones within the temple complex, partly by the requirements of the narrative to be painted, and partly by the architectural taste and desires of the artist and patron. Many Italian Renaissance artists focused on the temple porch. Its appeal for painters partly lay in its exterior approachability, and in the way in which a portico or loggia can be used as an open framework to assist visual access for viewers, and to magnify the figures within the image. Pictures designed around entrances become visual portals themselves. Italian architects excelled in designing porches, loggias, porticoes, and arcades – all structures which sheltered arrivals, departures, and the social loitering and extended rituals surrounding those poignant moments of separation and coming together. The architecture of the porch pronounces upon the importance of these daily rites; but as a structure it also juts out to tell or forewarn visitors and the public about the type of building they are looking at, and the wealth, taste or piety of its owners and inhabitants.

Architects such as the anonymous designers of the arched atrium of San Marco in Venice, or Brunelleschi in his loggia for the Ospedale degli Innocenti, or Giuliano da Maiano who probably added the porch to the Pazzi Chapel (fig. 35), had long been working with these structures; but painters could still contribute radical new thinking in response to the idea of the Beautiful Gate or Solomon’s Porch.

The paramount example is Raphael’s tapestry cartoon of ‘The Healing of the Lame Man’ (fig. 36), for which he generated a new design for the Temple porch using the highly distinctive architectural motif of the twisted spiral Solomonic column, chosen because the early Christian basilica of Old St Peter’s housed 12 such columns, placed in a double row to create a screen in front of the chancel and entrance to Saint Peter’s shrine (‘Confessio’).30

Some of these ancient columns were reused in the new St Peter's (fig. 37). Raphael therefore not only adopted the motif from Old St Peter’s, but also deployed it in an analogous way to create a type of screen passage in front of the Temple. In the 15th and 16th centuries the ancient spiral-fluted columns in Old St Peter’s were thought to be relics from Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, confirmed by an inscription added by Cardinal Orsini in 1438.31 Although Acts 3: 2 and 9 refer to the Healing of the Lame Man taking place at the ‘Beautiful Gate’ (‘Porta speciosa’) of the Temple, Raphael could equally have built his image around the reference to ‘the porch that is called Solomon’s’ where, just afterwards in verse 11, the cured man held on to Peter and Paul and a crowd of people came to watch and wonder.32

There were other key factors in favour of the Solomonic column. Unlike most architectural orders which proclaimed their sturdy, immobile solidity – their ‘firmitas’ – these columns were decorative, playful and pliant. They almost seem to defy the very principle of the column as an emblem of straightness, stasis and support, appearing to buckle under the weight of the roof, twirling with the optical illusion of their curving diagonal grooves. Raphael reproduced the detail of the ancient columns precisely, exploring the exuberant relief sculpture that winds around their swelling shafts with athletic putti and meandering grape vines, each different from its neighbour. This too goes against the notion of the architectural orders then being formulated, in which columns should match each other and stand for consistency and continuity. Is it possible that Raphael’s celebration of twisted forms was intended to draw attention to the twisted legs of the lame man seated at the foot of the foremost column?

The architecture in Raphael’s cartoons, particularly in his depiction of Solomon’s porch, assumes great presence. Raphael achieves this through scale, viewpoint and positioning of the building within the picture. His enlargement of both figures and architectural setting is clear if we consider the tapestry of ‘The Healing of the Lame Man’ as it was designed to be hung below Botticelli’s ‘Healing of the Leper’ fresco in the Sistine Chapel (fig. 38).

The temple in Botticelli’s fresco is set back behind all the figures like a backdrop or a flat image of a building, whereas Raphael’s much bigger temple porch juts forwards and stretches back into the shadow, dominating with its sense of mass and plasticity. Raphael brings the architecture forwards, close to the picture plane, particularly the front three columns which loom in an astonishing way, seeming to bulge towards us, with their bases running along the bottom edge of the picture, establishing a low viewpoint. Likewise, at the top of the picture the foreground columns soar out of sight, placing the viewer at ground level among the columns along with the disabled, the disciples and the visitors to the temple. Another crucial feature is the interaction between architecture and figures. Raphael places people around, among and between the columns, so that the space is fully inhabited and it seems to come alive as a place. This is in absolute contrast to the cool sterility of 15th-century ideal city views with their depopulated piazzas.

The manipulation of light also contributes to the columns’ looming presence. Raphael explores the essential characteristic of a porch or portico that it is both inside and outside. The cartoon moves from an exterior foreground, with daylight playing on the reliefs cladding the columns, to the gloomy recesses of the temple interior, artificially lit by smoking lamps (fig. 39).

This transition from outer to inner porch, moving towards the walls of the temple itself, creates a sense of mystery and anticipation, leading towards the Holy of Holies which must lie beyond the dimly seen archways within archways. Changing light levels are used to enhance the three-dimensionality of the columns as well as their modulated sculpted surfaces, to create spatial zones within the architectural complex, and to convey layers of narrative meaning.

John Shearman argued that Raphael depicts the side of the Temple, with the court where women offered sacrifices after childbirth in the left background.33 Rather than projecting a clear sense of the building as a whole, or of how this part of the Temple might relate to the rest, Raphael is ultimately more concerned with creating a grand ‘vestibulum’ or entrance area expressed through multiple columns. It is the forest of columns (19 are visible and many more implied) which dominates the image, just as it was the late decision to use this unusual type of column that enabled Raphael to animate the whole architectural setting.

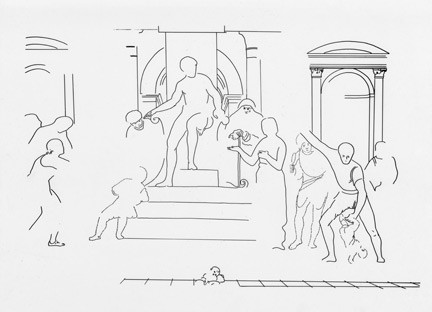

In Lodovico Mazzolino’s ‘Christ disputing with the Doctors’ (fig. 40) an inscription removes any doubt about the identity of the building by announcing that this is ‘the house which Solomon built unto the Lord’.34 The Hebrew inscription (fig. 41) seems primarily designed to establish the historic and geographic authenticity of the work, performing the same sort of role as the Solomonic columns in Raphael’s cartoon.

It may also have been intended to address a specialist audience of Jews and scholars, although Hebrew inscriptions were widely used when evoking the Temple in Jerusalem. Although the architectural design is entirely different from that in Raphael’s ‘Healing of the Lame Man’, the idea of the Temple porch as an entrance threshold and architectural proclamation is just as crucial here, as is the placing of the figures within its sheltering structure. The outer gateway, which is supported in the foreground by rectangular piers, is surmounted by an elaborate white marble tympanum or pediment. This is carved in relief with a battle scene with armoured horsemen, reminiscent of those on Roman sarcophagi, but it seems also to incorporate the figure of young David grasping the head of Goliath in the centre foreground (fig. 42).35

Behind this frontispiece, the coffered porch rests on four pinkish marble columns, while the doorway of the Temple itself, flanked by statues in niches, leads to an inner tabernacle incorporating a sculpted relief of Moses presenting the Tablets of the Law under the Hebrew inscription.36 The reliefs look Roman but represent Old Testament subjects with clear references to Moses and David, who both ante-date Solomon’s building of the Temple. So Mazzolino imagines a Temple in which Solomon pays homage to Moses the lawgiver and King David his father, presented here as a boy in reference to Christ as a boy in the Temple. Significantly, the fictive relief with Moses is set up immediately above the elders in the Temple who are expounding the Old Law established by Moses, arguing with the young Christ who expounds the New Law.

The projecting structure of the porch with its finely carved marble ornament resembles the micro-architecture of contemporary ciboria (canopies), rood screens or even tombs, particularly those in Venice, which incorporated reliefs, becoming amalgams of architecture and sculpture. Whereas Raphael viewed his porch from very close-up with little sense of the whole temple behind it, Mazzolino’s building is conceived as a centrally planned structure, a true ‘tempietto’ form inspired by the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, with a great drum of white marble to which a magnificent porch has been attached. This is an audacious scheme, like a miniature version of the Pantheon but with a different type of porch, not matched by built architecture at this date.37

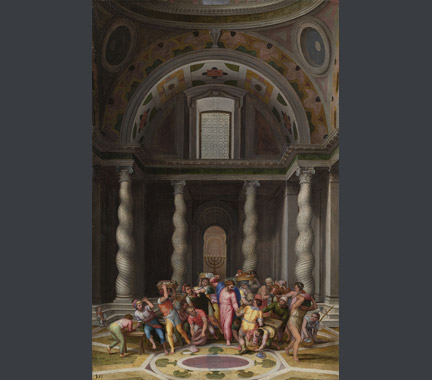

Marcello Venusti’s ‘Purification of the Temple’ (fig. 43) derives from the Gospels, which all place this episode inside the Temple, not in front of its façade as Giotto portrayed it in the Scrovegni Chapel (1303–5).38 Despite the relatively small size of the picture Venusti conveys monumentality through his architectural plan of a domed crossing (suggesting the whole building is a Greek cross, although we cannot see enough to be sure) which creates a vast, open central space and soaring height. Even though less than a quarter of the dome’s rim is visible in the painting, this is sufficient to suggest a far greater height beyond. Splendour is also created by the choice of a colossal version of the Solomonic column, and by the deployment of rare coloured marbles cladding the whole pavement, walls and arches. Equally effective is his manipulation of scale, since the comparatively small figures are dwarfed by the architecture, achieving a magnificent effect for the Temple, but diminishing the impact of the narrative.

The screen of Solomonic columns in Old St Peter’s was once again a starting point for the highly decorative version of the Temple in Venusti’s picture. Giulio Romano’s ‘The Donation of Rome’ in the Sala di Costantino in the Vatican Stanze can be taken as a more faithful rendering of Old St Peter’s before the second set of twisted columns was removed in 1592 (figs. 44 and 45),39 and this reveals how Venusti was not so much interested in recording Old St Peter’s, as in working with ideas for the new St Peter’s based around a Greek cross plan. He also deployed the Solomonic columns in a new way, turning them into a giant order to support the entablature and the great arch over one of the projecting arms of a Greek cross.

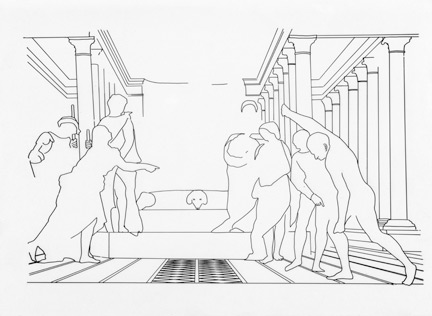

Sebastiano del Piombo’s ‘Judgement of Solomon’ (fig. 46) presents an entirely different idea of Solomon’s architecture, based on the building type of the basilica shown in perspectival cross-section.40

This architectural solution for representing the interior of a great church or temple goes back to Sienese painters of the late 13th and early 14th centuries, to Ghiberti’s ‘Solomon and Sheba’, or Francesco Rosselli’s print of ‘The Presentation of Christ in the Temple’ (British Museum), and to works produced in the Veneto, closer to home for Sebastiano at this point. These include Altichiero and Avanzo’s ‘Baptism of King Sevio’ in the Oratory of San Giorgio in Padua (fig. 50) and Jacopo Bellini’s drawings of ‘The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple'.

All these images employ the tripartite structure of the opened-up basilica to create a strong compositional anchor for the figures and the narrative, as well as using architecture to evoke a sacred place that fuses ancient temple and modern church.

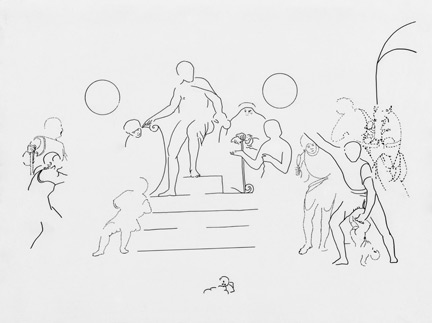

Sebastiano may be representing his idea of the Temple in Jerusalem here.41 Yet, if he knew that basilicas were used by the Ancient Romans as legislative chambers and council halls, he may have conceived of this as a secular building, as a tribunal rather than a temple.42 His exploratory approach to the whole question of how to create an architectural setting for the Judgment of Solomon is evident in X-rays and infra-red reflectograms revealing the underdrawings and preparatory phases of two quite different earlier architectural schemes (figs. 48–50).43

The first involved two big roundels either side of the throne and part of an arched opening to the far right, while the second had two large framed niches or windows surmounted by segmental pediments, with a massive arch and a cloth of honour behind Solomon.44

© Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge.

Both these phases were less encompassing architectural schemes, based around motifs rather than a full plan and elevation.

© Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge.

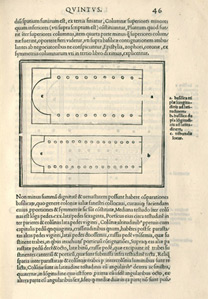

The basilican idea was therefore a fairly late and much more ambitious development, which may have been inspired by the first illustrated edition of Vitruvius, edited by Fra Giocondo and printed in Venice in 1511 (fig. 51). It included plans for basilicas with columned aisles and an apsidal tribunal at the far end.45 But even if Sebastiano was still working on the picture in 1511 and knew Fra Giocondo’s edition, he made a bold decision when he departed from the Vitruvian model by conceiving of a double-aisled basilica.

As in the case of Raphael’s ‘Healing of the Lame Man’, Sebastiano’s approach to scale is highly significant. His columns appear massive even though they are not actually tall in relation to the figures. The grand effect is achieved by other means, partly by the columnar form itself, by the grey veined marble of the columns, and by their being closely packed, creating the effect of profusion. Eight columns can be counted in the arcade immediately to the right of the dais, close to the nine columns on each side of the nave in the basilica on the Venetian island of Torcello, which are also monolithic grey veined marble (fig. 52).

Although they are unfinished, Sebastiano’s capitals (fig. 53) lack the bold sculptural quality and sense of organic growth or fleshy substance in the acanthus leaves which ancient capitals display; but they do conform closely to contemporary Venetian capitals carved ‘in the ancient manner’ by Pietro Lombardo and his workshop, as well as to Sebastiano’s own capitals in the organ shutters for San Bartolomeo a Rialto (fig. 54) .46

It is ultimately the perspectival scheme and the creation of an encompassing architectural environment, surrounding the figures and brought closer to the viewer, which lends such extraordinary power to this architectural invention. And within this scheme it is the aisles in particular that broaden and deepen the whole composition to create a sense of great spaces extending into the distance. The repetition of the columns increasingly compressed as they recede until they are almost fused and seem innumerable, gives a sense of a building whose splendour can only be imagined rather than known.

For most artists the Temple in Jerusalem was an architectural idea rather than an actual building; nor is the Temple easily definable or stable either as an idea or as a building. In the oeuvre of a single artist such as Giotto, multiple Temples appear even on the walls of one fresco cycle. Whereas Giotto used consistent physiognomy and dress for his figures so viewers could recognise the saints, no such rules applied to the Temple, which appears eight times in the Scrovegni Chapel (1303–5), in four quite different guises.47 As we have seen, it could be centrally planned like the Dome of the Rock, or it could be a longitudinal basilica like the earliest Christian churches then visible in Italy. Artists could focus on its porch, its interior, or on an interior/exterior cut-away combination. This could be interpreted as an identity crisis for the Temple, or the Temple can be seen as a springboard for artists, launching them into an inventive mode, offering them a space in which to design buildings unfettered by the client’s concern with the inclusion of specific figures.

In painting places and designing settings, artists created architecture that responded to and altered the subject matter in profound ways. From a real place such as the Piazza della Signoria, which turned ‘The Portrait of a Man in Armour’ into a patriotic civic image, to an imagined Temple in Jerusalem – which was the ultimate symbol of a sacred site lending to each simulacrum a little of its sanctity and an awareness of the Holy of Holies behind the picture – in each case architecture was essential for the meaning and aura of the work.

On another level, the ‘locus’ or place informed an artist's fundamental approach to composing a picture when the position of the viewer was co-ordinated with the design of the image.48 Thinking about this relationship lay behind Sebastiano’s decision in ‘The Judgement of Solomon’ to carry the pavement of his basilica forward to the edge of the picture and to make the whole building seem as though it were continuing around the viewer, stretching out either side and receding into the distance. Raphael’s decision in ‘The Healing of the Lame Man’ to bring his columns right forward and to populate his architecture with a crowd pressing towards us is another case of an artist creating an impression of place by involving the spectator with the building. In both cases the design of architecture in relation to the viewer produces a feeling of immediacy and physical presence. This too creates a sense of place.

Read further sections in this essay

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Between real and imagined Places

- 3. Between street and piazza: the Florence of Saint Zenobius

To cite this essay we suggest using

Amanda Lillie, ‘Place Making’ published online 2014, in 'Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting', The National Gallery, London, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/place-making/imagining-the-temple-in-jerusalem