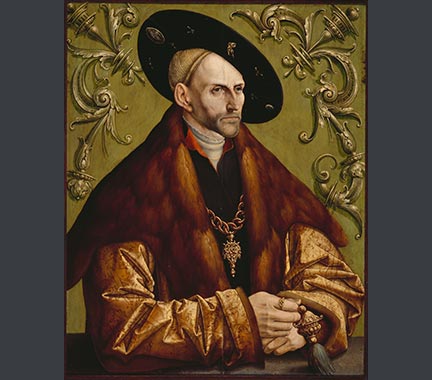

German

'Edzard the Great, Count of East Friesland', 18th century

Oil on oak, 48.9 x 36.2 cm

NG2209

Dendrochronology provided key evidence in determining that this painting was produced in the 18th century, approximately two centuries after the lifetime of the sitter. The portrait may have been produced in response to a historical interest in the sitter, Edzard I, Count of East Friesland.

Identity of the sitter

An inscription on the back of the painting’s oak support wrongly identifies the sitter as Ulrich I Cirksena (died 1466), Count of East Friesland.

The head and hat of the sitter are actually based on portraits of Ulrich’s son, Edzard I (1462–1528), known as ‘the Great’, who became count in 1492. Edzard wears armour and carries a sword inscribed ‘Victor est qvi in / nomen domini pvgnavit’ (The victor is he who has fought in the name of the Lord). The badge on his hat is decorated with an eagle, part of the arms of East Friesland. When the Cirksena dynasty died out in 1744, East Friesland was absorbed into the Kingdom of Prussia. It is now part of the German state of Lower Saxony.

Netherlandish or German?

Between 1911 and 1929, the National Gallery’s painting was attributed to the Dutch painter Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen (before 1470–1533). This was because of a perceived relationship to another portrait of Edzard in Oldenburg, Germany, then considered to be by that artist.

© Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Oldenburg, photo S. Adelaide

It was proposed that Cornelisz had painted Count Edzard when the latter travelled through the Netherlands in 1517. In reality, both the Oldenburg and London paintings more closely resemble German portraits from the early 16th century. It seems more plausible that Edzard would have been painted locally, rather than on a hurried trip through the Netherlands.

Determining the painting’s age

As early as 1945, Gallery curator Martin Davies suspected that this likeness might be a later copy rather than a 16th-century original. In 1993, dendrochronological examination of the painting’s wood panel support found that the oak was Netherlandish or Western German in origin, with growth rings formed between 1562 and 1695. Based on this evidence, and allowing for trimmed sapwood rings and sufficient storage time to season the wood, the earliest possible date for the painting would be about 1704.

Analysis of a paint sample taken from the greenish-grey background in 1994 identified lead white, black, a brownish red iron oxide pigment, vermilion and one particle of what appeared to be Prussian blue. As this last pigment was only discovered between 1704 and 1710, its presence corroborates the approximate dating of the oak panel through dendrochronology.

Why was it made?

The National Gallery’s Edzard the Great, Count of East Friesland may be a straightforward copy of another portrait, now lost, or it may be a pastiche based on the likeness in Oldenburg. Several other 18th-century ‘portraits’ of various counts of East Friesland exist. The end of the Cirksena dynasty in 1744 may have stimulated a flurry of nostalgic interest in manufacturing these historic likenesses.

Marjorie E. Wieseman is Curator of Dutch paintings at National Gallery. This material was published on 30 June 2010 to coincide with the exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries

Further reading

M. Davies, ‘National Gallery Catalogues. The Early Netherlandish Schools’, third edn, London 1968, p. 148