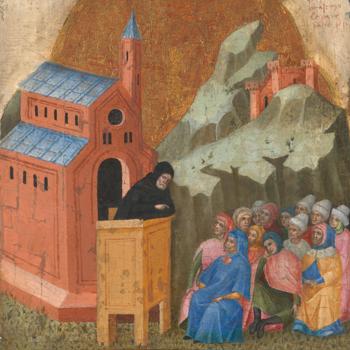

Dalmatian/Venetian, Helsinus saved from a Shipwreck; A French Canon drowned

Altarpiece of the Virgin Mary

This altarpiece is a unique example in the National Gallery’s collection of a work made by a late medieval artist working on both sides of the Adriatic, the sea between Italy and the Balkan coast. The picture may be one of the earliest painted representations of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (the Virgin being conceived without sin). This was a controversial idea in this period. It was not officially included in Catholic theology until the nineteenth century, but it was celebrated in the fifteenth century, on 8 December.

The central panel showing the Virgin and Child includes celestial bodies – the sun, moon and stars – that became associated with the Immaculate Conception. The left side panels show the story of the Virgin’s miraculous birth to a couple who could not have children; the right side panels shows two miracles of the Virgin.

This altarpiece is one of very few paintings in our collection made by an artist working on both sides of the Adriatic – the sea between Italy’s eastern coast and an area known as Dalmatia (modern-day Croatia). These coastal regions were closely connected in the medieval and Renaissance periods through trade and artistic exchange, particularly through Venice. This is the only work in the National Gallery that reflects this relationship at around the year 1400. It includes motifs found in images created in both Venice and the coastal towns of Dalmatia such as Zadar. Carlo Crivelli would be the most famous artist to maintain these artistic links in the later fifteenth century.

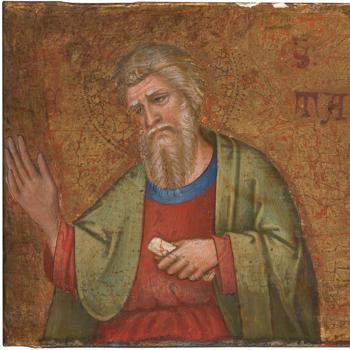

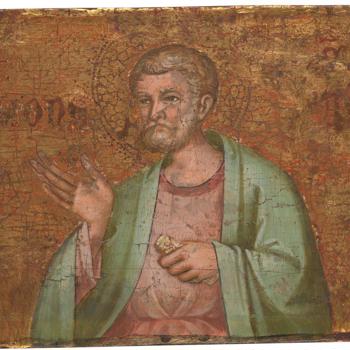

The altarpiece is made up of five vertical panels, and each side panel has two narrative scenes; the stories run from left to right, and top to bottom. The Virgin Mary and Christ Child are shown in the main panel. Scenes of the lives of Saints Joachim and Anne appear on the left side panels, including the birth of Mary, their daughter. The right side panels show two miracles of the Virgin, one involving a so-called English saint Helsinus – who was actually never canonised – and the other a French canon.

The central panel is a very early image of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception. The Feast of the Immaculate Conception was not officially part of Catholic dogma until the mid-nineteenth century, but in 1477 its celebration was sanctioned by the pope. The Feast had long had supporters in England. In the twelfth century an Anglo-Saxon monk called Eadmer wrote about the sinlessness of the Virgin Mary’s conception. His text, De Conceptione Beatae Mariae Virginis (On the conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary), sparked controversy that lasted centuries. Some believed that the Virgin was sanctified – or made sinless – in the womb after her conception, while others maintained the conception itself was sinless. In his text Eadmer included the miracles of the Virgin shown on the right-hand panels of this altarpiece; the artist obviously knew the text and used it as a source for his images. In the early fourteenth century the Franciscan theologian Duns Scotus promoted the argument for the Virgin’s Immaculate Conception and Franciscan religious groups began to celebrate the Feast at around this time.

We don‘t know if this altarpiece was intended to celebrate the Immaculate Conception or just the conception of the Virgin. The miracles of the Virgin don’t explicitly refer to her sinless conception. The altarpiece was made almost a century before celebration of the Feast received official sanction, and though it was observed during the fifteenth century it remained the least celebrated of all Christian festivals. There were many Franciscans on the Dalmatian coast where this picture may have been made, and there is evidence that many altars in the Dalmatian town of Zadar were dedicated to the Virgin’s conception. But the date of these dedications is either later than this picture or unknown, so we can't connect this altarpiece to a particular church.

The imagery used in the central panel – the moon, the stars and the sun – became associated with image of the Immaculate Conception later in the fifteenth century. Their use here, as well as the reference to Eadmer’s text, suggests that the panel may be a very early image of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception.

We can only speculate about the identity of the artist, but we do know he had a unique style. His storytelling in the narrative scenes is clear and simple, focusing on a few figures but setting them against varied, generally landscape settings. He enjoys playful details such as a shepherd playing the bagpipes and men throwing cargo overboard. He uses the same few colours – red, green, pink, blue and some yellow – to unite the various images. His figures have exaggeratedly almond-shaped eyes with well-defined lids and long, dainty fingers.