At the National Gallery

A new gallery for post-war Britain

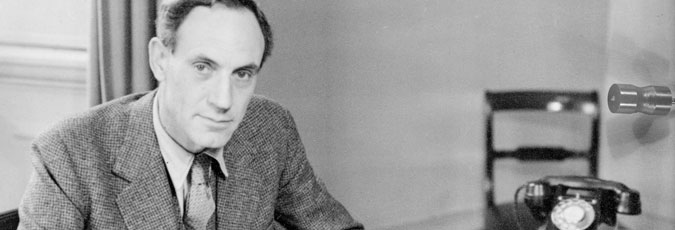

In 1946, Hendy succeeded Sir Kenneth Clark as Director of the National Gallery, and would become its longest serving director to date (January 1946 – December 1967). Hendy’s most immediate task was to rehabilitate the Gallery for the display of pictures after they had been returned from Wales, where they had been kept in safe storage during the Second World War. An admirer of Clark’s curatorial approach, Hendy wanted to extend his policy and make the National Gallery central to Britain’s cultural life.

An active player in the origins of cultural policy during wartime, Hendy had called upon museums and galleries to democratise access by making their displays more modern, open, and easier to navigate. Wreckage caused by air raids afforded opportunities to refashion the Gallery’s interior and displays, and this led to a substantive effort in modernisation. However, Hendy’s project of renewal was met by material and financial shortages, and the full reopening of the Gallery had to wait for another 10 years (in 1956). Despite these shortcomings, the attractiveness of the new galleries quickly gained public acclaim, and this modern public face was matched by the reorganisation of various departments, making the National Gallery a modern and efficiently run institution (encapsulating Conservation, Scientific, and Publications).

Reopening the Gallery

As early as December 1945 the entire picture collection had been returned to the main site in Trafalgar Square, and 19 out of the existing 29 rooms were soon rehung, in the east wing of the National Gallery. Working under difficult post-war conditions, Hendy’s makeshift rehang challenged the arrangement of artworks by schools as we know it today. Rather than displaying works belonging to the same school of painting, the National Gallery under Hendy displayed paintings of contrasting chronologies and geographies as an ensemble. Hendy saw in these ‘daring juxtapositions’ an aesthetic arrangement that could encourage viewers to look at paintings with a direct and unhampered vision. In the belief that artistic exchanges travelled beyond national borders, Hendy wanted to expose visitors to the dialogue between paintings, such as Titian and Rubens, Holbein and Bronzino, or El Greco.